Food for the Soul: A Taste of Klimt in Vienna

Artworks by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), the most popular representative of Viennese Art Nouveau, grace collections all over the world. After a protracted restitution battle, one of the most famous of his gold paintings, the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, is now in New York; galleries in cities like Tokyo, London, Tel Aviv, Venice, and many others each have a picture or two. Popular culture is awash with Klimt’s images, from bedroom poster decorations to nylon tote bags, often using just a few decorative elements from large compositions. On the other side of the spectrum there are movies, such as the enormously entertaining Woman in Gold or the just-produced Klimt & The Kiss in the Exhibition On Screen series.

However, it is Vienna, the city where Klimt worked and died, that is still the location of the greatest collection of his canvases, including the eternally popular The Kiss and his wall decorations in the hallway of the Kunsthistorisches Museum and other buildings throughout the city. Since the Belvedere gallery alone boasts of the largest number of Klimt’s works, it is a perfect place to compare the artist’s evolution from a fascination with styles that preceded him, from Impressionism to Pre-Raphaelites, to a style that was absolutely his own—unique and groundbreaking.

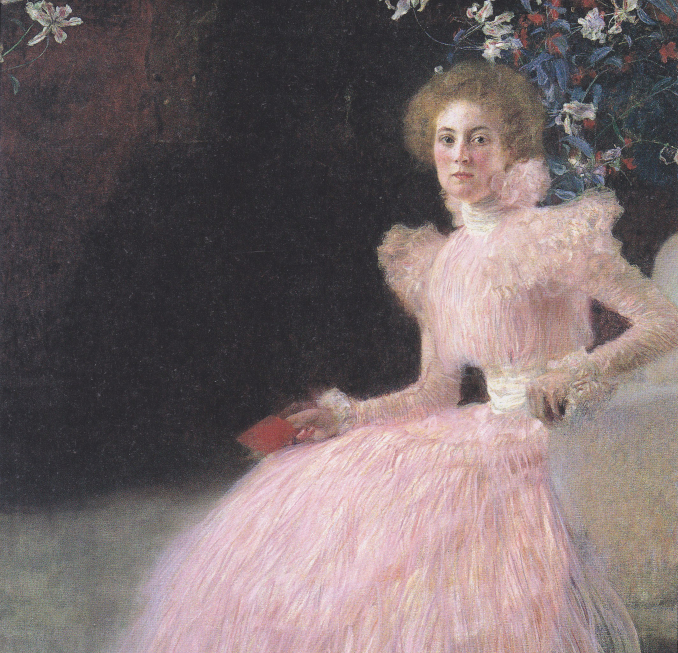

His portrait of Sonja Knips illustrates this transition well. The sitter, baroness Sonja Potier des Echelles was a long-time friend of the artist and one of his earliest patrons. At the time when she posed, she had already been married for two years to an industrialist named Anton Knips, but the expected “serious” countenance of a married woman is ignored here in favor of a very romantic, “girlish” look.

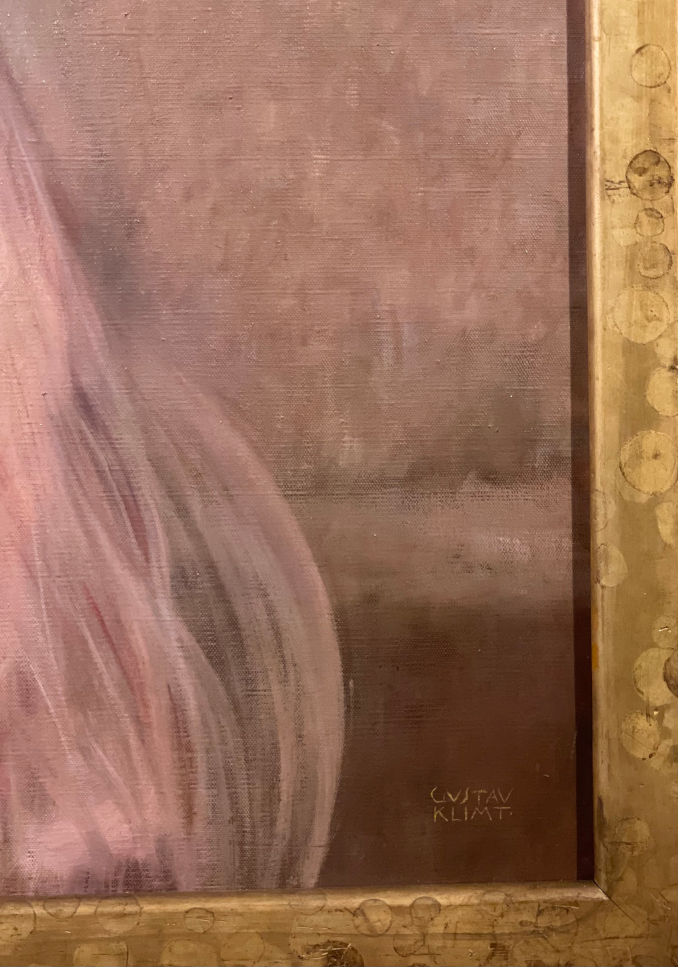

Her pink tulle dress is rendered with wisps of energetic brush strokes and her pose of leaning forward suggests capturing a movement—both are hallmarks of Impressionist-style portraiture. Only the sitter’s face betrays Klimt’s unique style of blending colors into a luminous surface. From about 1895, his models’ skin takes on a luminescence of shimmering pastel colors, a style of rendering skin’s texture that he invented.

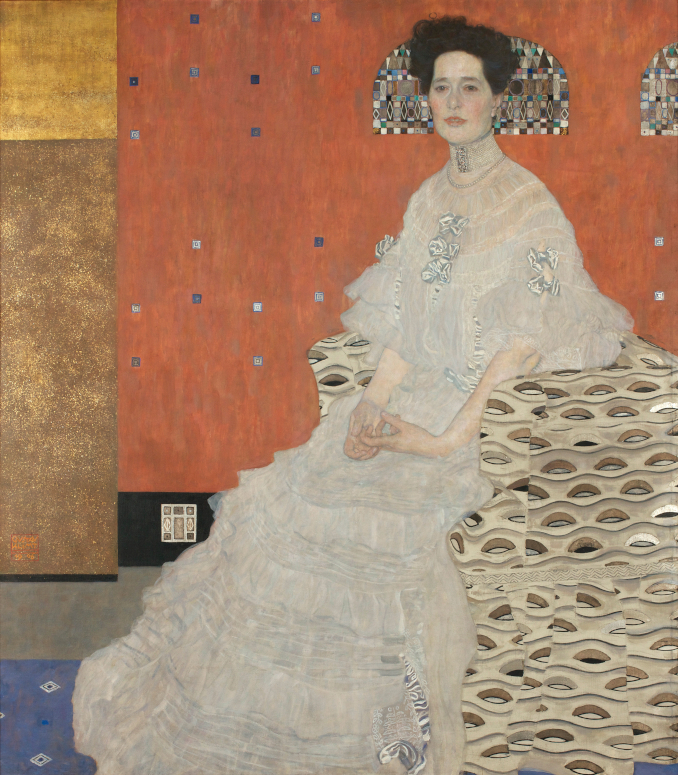

By the time Klimt started painting his gold pictures, the faces would all have that unique “decorative” shimmer. The naturalism of a picture background (e.g., a garden or a room setting) would disappear in favor of geometric compositions, more and more often enhanced by textured patterns of such non-paint materials as gold leaf, enamel, or even gemstones. Portrait of Fritza Riedler, painted less than 10 years after Sonja Knips, is an example of this change in Klimt’s style.

It was not only the way he painted that radically changed. The artist also became a leader of the new Secession style, in a city that was socially fossilized and artistically entrenched in 19th-century Academism. Klimt and contemporaries such as painter Egon Schiele and designer Josef Hoffmann led a stylistic revolution that rejected fussy Victorian design and academic realism in favor of symbolism, also establishing new linear stylistics in the decorative arts, furniture, and architecture.

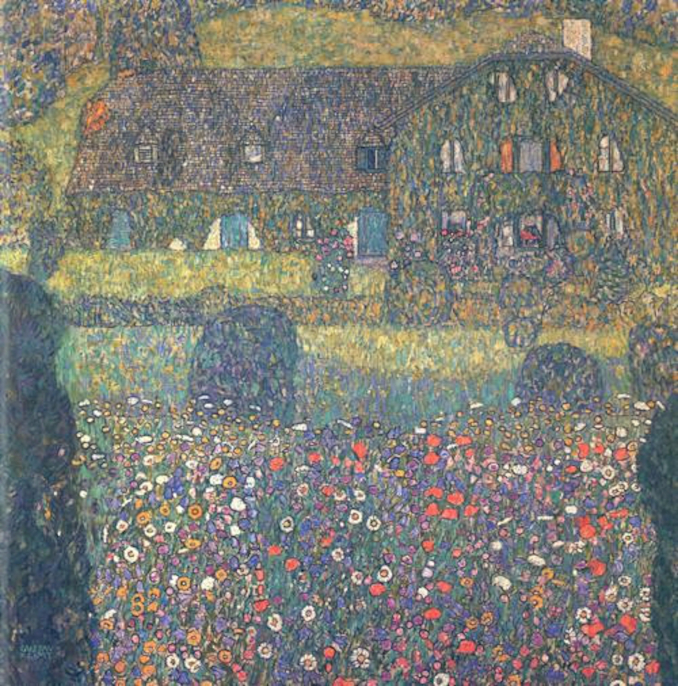

Like most Europeans up through the present day, Klimt would spend summers away from the city, escaping both the heat of stone walls and the pressure of social and professional duties. His vacations in country houses, mostly in the company of his muse Emilie Flöge and other friends, would inspire him to paint in a completely different genre. Instead of complicated portraits adorned with gold leaf, he would paint landscapes—masses of greenery and flowers, shimmering lake waters, and barns or buildings that looked mysterious hidden in invasive vegetation.

Take a look at Litzlberger Keller, a view of a restaurant on a lake. If you look closely, he has hardly used any regular “grass-green” hues. Grass in this picture is mostly light acid-green with dots of blue and yellow. The trees are mostly painted blue-green—that shade of emerald is lovely to look at, but it feels very artificial when compared with the color of real leaves. Klimt’s palette is full of those “unnatural greens” as well as strong purples and blues, from royal blue to cobalt. Klimt’s unique relationship to colors is quite enchanting in both the Litzlberger Keller and Farmhouse in Buchberg, a view of two trees in the front of a flowery meadow leading to a wooden house.

In both pictures, Klimt chose not to paint the windows black or gray, which would have been logical colors to indicate the darkened inside of a house. Instead, he painted in some stripes of vivid green, purple, blue, and copper—colors that he must have felt echoed the ones he picked for the trees and the meadow.

Lajos Hevesi, an art critic contemporary with Klimt, described the artist’s method of using a few strong colors to create a highly subjective interpretation of the landscape as “painted mosaic.” Even when Klimt was painting a country garden or a lakeshore, he was still decorating—arranging colors, shapes, and light or shadows into an image through small dabs of color that would give a shimmering picture when viewed from a distance.

Symbolism, an art movement of the early 1900s in which Klimt was one of the main innovators, was a reaction against the previous century’s rigidity, uniformity, materialism, and belief that science and technology could explain, improve, or change everything in people’s lives, including their bodies and minds. Symbolists were interested in the opposite: the immaterial life of body and soul as well as sexuality and death as an exploration of different states of consciousness. Some of Klimt’s works were directly connected to the ideas of symbolism—for instance, with his very unequivocal illustration of the human condition in Death and Life. Others, especially his landscapes, at first glance do not appear symbolic. It is only when we compare them with a typical, naturalistic landscape, such as by Théodore Rousseau or Albert Bierstadt, that the extent to which Klimt’s eye was attuned differently becomes evident. He took a landscape around him and made it part of his visual panorama. He would rearrange and mix colorful dots that would represent flattened and enlarged views of plants or buildings, water reflections, or fragments of bark or leaves. For our 21st-century eyes, these “manipulated” landscapes are familiar from so many works of art that came after Klimt (anything from Picasso to Hockney), but in the early 1900s, these pictures must have been as shocking as any erotic drawings by Schiele or abstract art by Kandinsky.