Food for the Soul – Cat Stories

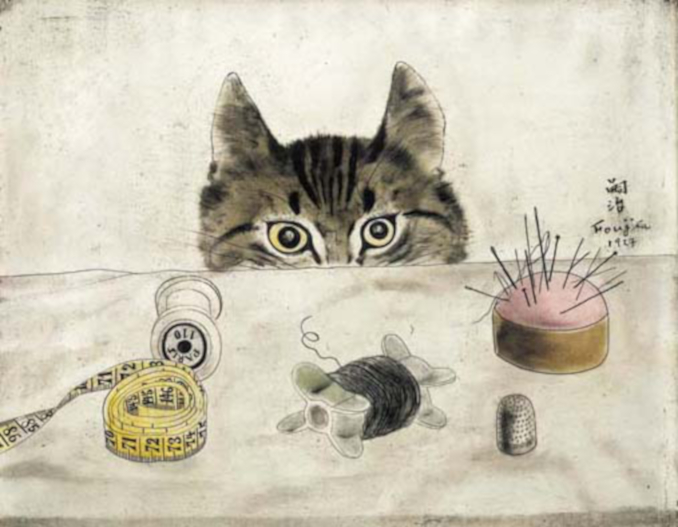

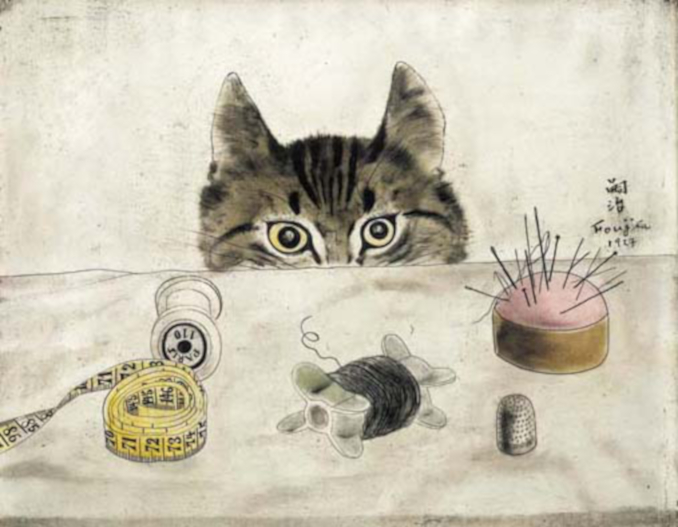

Couturier Cat. Tsuguharu Foujita. 1927. Photo: Public Domain Wikiart.org

Before there were videos of funny cats on the Internet, for about 4000 years there were simply fun cat paintings.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Long before the entire world got stuck in front of flickering screens all day long, cat videos were the most popular item on the Internet. The coronavirus lockdown has only brought the cat-viewing craze forward. To join in on this feline domination of the visual world, here are some cat stories from the world of art.

Actually, the history of art reflects quite accurately the changing attitude of humans toward cats. Revered in Egypt as helpful hunters and grain-protectors, they achieved a divine status. Taken down a few pegs to being useful but not divine during the Greco-Roman period, they ended up persecuted, compliments of Christianity’s association of a cat with a devil. Only around the 17th century did they start recovering a better reputation, mainly thanks to cats’ tireless ability to hunt grain-eaters, and to people’s rising standard of living, which encouraged pet ownership. Cats started to appear in paintings as symbols (of sexuality or even death), then as sugar-sweet decorations in kitschy Victorian illustrations, and in modern art as mysterious blobs of interesting shapes and colors. By now, there are thousands of works of art featuring cats in all genres, from folk art to fine art.

Although traces of feline domestication can be proved for thousands of years before the kingdoms of ancient Egypt, nowhere have cats achieved such a lofty status as under the reign of pharaohs. Statuettes, temples of the Goddess Bastet, and cat mummies can attest that felines were respected, mourned, and buried with the same reverence as humans. Moreover, Egyptian tomb and temple paintings show cats as pampered pets, sitting under chairs and close to (female) owners’ legs, playing or eating a snack. Clearly, cats were not only an embodiment of divinity but also favorite house pets. Unlike in modern times, though, cats also had a working role as hunting companions. There are carvings and paintings of cats flushing out birds, the most famous of these images being a tomb painting from the 18th Dynasty (about 1350 BC). A hunter is aiming a throwing stick at a flock of water fowl that the cat is flushing out. Since both the man and the cat are on a flimsy reed raft surrounded by water, I guess the cat had no choice but to stay close. Egyptians must have been masters at getting cats to cooperate, a feat never to be repeated in history. You do not see paintings of knights on a hunt with a pack of cats.

Fresco from the Tomb of Nabamun. c. 1350 BC. British Museum. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

If you were a courtier of Queen Elizabeth I, it was not a good idea to displease her, and even less of a good idea to participate in a rebellion. Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, did both. First, he incurred the Queen’s displeasure by marrying her lady-in-waiting without royal permission and by being generally a quarrelsome bother. To top it off, he then took part in the Essex Rebellion against the monarch. He was lucky enough just to lose his freedom and not his head, but he did spend a couple of years in the Tower. He shared his cell with his pet Trixie, a classic black and white tuxedo feline. The earl claimed that the faithful pet followed him all the way to the prison tower, but judging from the cat’s expression, Trixie must have been brought to his cell against her will. When the Virgin Queen died in 1603, the earl was released and became a court favorite of the successor King James I—and then he had this unusual portrait painted. Unusual because the custom at the time was for men to be portrayed with hunting dogs rather than cats, but Trixie clearly deserved recognition, pissed-off expression or not.

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. John de Critz (attributed). 1603. Private Collection. England. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Here is another cat being annoyed by its owner, this time during an attempt to be brushed. The white angora cat is trying to swat away at a brush while its determined tormentor is a society lady, all dressed up in a fancy hat and silk dress. The cat itself is very fancy, because angora cats, imported from Turkey, were rare and fashionable in France at the time, eventually to be replaced in the 19th century by long-haired Persians. Marguerite Gérard was a sister-in-law and a student of the famous Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose name is on the painting as a co-author of this work. Marguerite painted other cats, like the much-reproduced and somewhat kitschy The Cat’s Lunch, but this painting actually shows off her (or Fragonard’s?) artistic skill, both in the cat’s movements and in the glass bowl that reflects images of the kitty and an unseen window.

The Angora Cat. Marguerite Gérard and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. 1783. Bernheimer Fine Old Masters Gallery Munich. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Over a thousand works of Francisco Goya at the Prado range from iconic royal portraits, to historical canvases such as The Third of May, 1808, and all the way to grotesque and pessimistic Black Paintings. The collection also includes a small cartoon for a tapestry intended to decorate a dining room palace of Prince d’Asturias. These tapestries were never produced, but the Cat Fight cartoon exists to this day. The same way that sharp-eyed Goya captured vacuous and conceited expressions of the royals in Charles IV and His Family, the artist accurately observed these two cat fighters: backs arched, ears flattened, and you can almost hear the ear-splitting screech of cats on a roof in March. It’s fun to spot such a work by an old master among all his serious and venerated canvases.

Fighting Cats (Gatos riñendo). Francisco Goya. 1786. Museo del Prado. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

All the way through the Victorian era and certainly with the advent of modern art, cats took center stage in paintings as stand-alone subjects, no longer just accessories to human portraits. Dozens of artists immortalized their beloved pets, including Picasso, Matisse, and Chagall.

In the 20th century, German artist August Macke is mainly known for his Expressionist and Fauvist works, especially the ones he painted once he got exposed to the Cubist art of Robert Delaunay. This painting was created earlier, when Macke was under the influence of Paul Klee, but this is hardly a work of abstract art. The orderly composition of vases and pots is enlivened and underlined by a strolling kitty. The calico pet seems to be in a very good mood—her eyes are closed and the tail is curled into a candy-cane shape. You can almost hear her purr. As lovely and luminous as the pots are, it is the cat who introduces the titular “spirit of the house” and makes the composition dynamic and complete.

Spirit of the House: Still Life with a Cat. August Macke. 1910. Lenbachhaus, Munich. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s trademark are those deceptively naive figures of bloated humans—they look like inflatable toys. This puffed-up appearance has carried over to his figures of animals, especially cats. This particular super-fluffy kitty is walking a street in Barcelona, cute but at the same a bit menacing. If real cats were this size and bulk, humans would think twice before trying to befriend them. So, here is a cat on steroids, both funny and threatening, waddling through a busy street. Botero uses his super-inflated figures painted in a primitive folk-art style to satirize but also sometimes to make a political or social statement. Cats show up in his paintings, often wearing the same expression as the women they accompany. His parody of van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait sold at Christie’s in 2012 for over $850,000, and it features a puffy kitty instead of the pet dog of the original.

Cat. Fernando Botero. 1990. Rambla del Raval. Barcelona. Photo: Canaan on Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Images of cats in Asia, from Japanese woodblock prints to Indian miniatures, would fill an entire book just by themselves, but here is an example of something simple and popular throughout Asia. This is a folk-art illustration of a well-known fable. So far, we have seen cats from the point of view of humans, but this one is from the point of view of a species that depends on cats’ goodwill. This is a rats’ wedding. You see a decked-out bride in a sedan chair, preceded by her fiancé on a horse (and shaded from the sun by a servant with a parasol). While this wedding procession is passing by, a second group of rats is approaching a big, fat, white cat. He is being offered fish and game to the accompaniment of music. The cat is being bribed to let the wedding go ahead undisturbed. Any reference to the human process of corruption is surely unintended.

Rats’ Wedding. Dong Ho folk art (Vietnam). Photo: Nina Heyn

Cats on the Internet are mostly cute and funny. In good art, cats may be less cute, but it’s still fun to spot them throughout art history.