Food for the Soul – Dog Stories

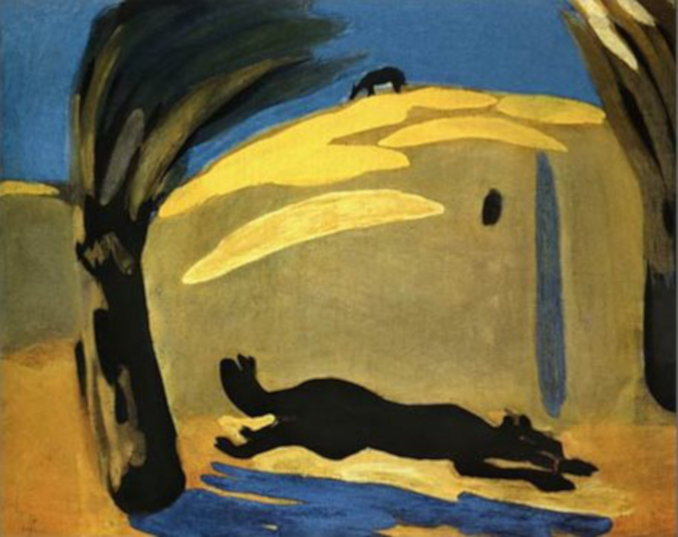

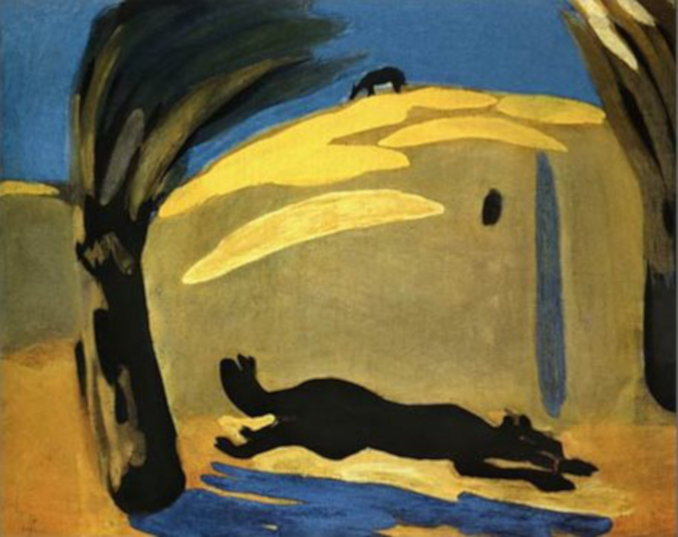

Martiros Saryan. By the Well. Hot day, 1909. Martiros Saryan Museum, Yerevan, Armenia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

“Man’s best friend” has been a friend of artists throughout centuries and esthetic styles.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

As soon as I wrote a story about cats in fine art, dog aficionados felt a bit slighted and requested some artistic dog stories as well. So here they are, by popular demand and to salute all the faithful four-pawed companions.

Helpers

Since cats long ago decided that pulling a sled in six feet of snow was best left to other species, dogs have taken over as human helpers in either guarding homes, finding avalanche victims, or helping to hunt. For a very long time, hunting was part of life—for some people as a major food source and for others as a social activity—but either way, hunting scenes have been expressed in art from the cave paintings onwards. Medieval and Renaissance art is full of hunting scenes because you could still witness a hunt as a common occurrence in a nearby forest.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is probably the most accomplished and famous 15th-century manuscript created for a French noble by several artists during his lifetime and then completed by another painter a few dozen years later. Until as late as the 1970s, historians simply dubbed this later artist as “Master of Shadows,” but recently he has been identified as being most likely Barthélemy d’Eyck, an outstanding illuminator of such manuscripts as the Morgan Book of Hours. Among other illustrations, Les Très Riches Heures contains twelve famous pages of castles and outdoor scenes. D’Eyck is considered to be the author of pages for the months of March, October, and December. Not only are the faces that he painted individualized and full of expression, but also, these paintings featured his signature shadowing around trees and people. December pages of monthly calendar books traditionally would have depicted the slaughtering of the pigs, but in this book the December illustration is that of a wild boar hunt. Here we have the hounds of hunt in action—large greyhounds sinking their teeth into a boar while the hunt masters are trying to restrain them. These are “elite dogs,” if you will—bred for big game hunting, well-fed, and pampered by their noble masters, they are accoutrements of wealth and power. Artistically, this is an amazing composition of dogs with multicolored coats and a multitude of limbs—all in a seemingly chaotic pile—with both dogs and people engaged in the thrill of the hunt.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. December, c. 1440. Musée Condée, Chantilly. Photo: R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojéda. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The next painting shows a different scale of hunting with just a few riders. Some local peasants recruited to be game beaters are piled on haycarts, and on horseback there are local landowners. It is a hunting scene from the Eastern forests of lands that are today Poland, Lithuania, or Ukraine. The happy hunter on his beautiful Polish-Arabian horse is dressed in a costume of a rider from the 17th century, so this is actually a melancholic trip down memory lane for an artist living two centuries later, when his native land had been wiped off the political map of Europe.

Józef Brandt was one of the leading action painters in 19th-century Poland, famous for his canvases of horses galloping through the Eastern steppes, hunting scenes, Cossack skirmishes, and historical battles. Had he lived a century later, he would probably have been an action filmmaker—his pictures have a narrative, are carefully staged, and are full of colorful characters in action. In Fox Hunting, the rider’s faithful companion is a working dog. He is intent on tracing the fox scent but, well-trained, he is walking carefully to stay out of the horse’s path. This is what Brandt loved painting the most: horses, dogs, and riders.

Józef Brandt. Fox Hunting (Polowanie na Lisa), c.1880. National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Companions

This French painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, a leading artist of the French Academicism, is themed around the classic story of the Greek philosopher Diogenes and his “search for an honest man” with a lantern. The 19th-century art patrons would know the underlying story well. In fact, Greek philosophy is still a part of the school curriculum in many European schools. The dogs surrounding Diogenes are supposed to be symbols of his “cynic” philosophy (“kynikos” meaning dog-like in Greek), but in this painting these canines are hardly metaphorical—they behave like real dogs and look like any attentive dogs grouped around their master. Their bodies are taut, their eyes fixed on Diogenes with that lovely total absorption that a dog can give to his favorite human.

Jean-Léon Gérôme. Diogenes, 1860. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Early 19th-century art in France was dominated by an academician approach to subjects (they should be distinguished, usually mythological or historical) and style (they should be painted in the “Grand Manner” of Raphael). Then along came Gustav Courbet, who declared that honesty and being down-to-earth in paintings were more important. Courbet coined the name of new style as “Realism” when he had his own art show in 1855 under this title. All his life, he was staunchly anti-establishment in politics and pro-realism in art. He created scandals by portraying prostitutes in a park in Young Ladies Beside the Seine or praising the toil of a working man in Stone Breakers. Even this relaxed painting of a few people meeting for a mountain walk has a hidden artistic manifesto. Courbet portrayed himself, carrying his portable easel and paints, meeting his friends (one of them is art collector Alfred Bruyas) who are on a mountain hike with a dog. Painted in a classic style and presenting the backpacking artist as someone in a respectable social situation, this was a poke in the eye to academician art, which would abhor such a mundane subject. The best in this painting is the happy dog, tongue lolling out, content to be in the great outdoors with his human companions. A farmer’s son, Courbet painted dogs often, including a great portrait of two greyhounds.

Gustave Courbet. The Meeting (Bonjour Monsieur Courbet), 1854. Musée Fabre, Montpellier. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The first decade of the 20th century was a period of fascination with technology in general and the speed of machines in particular. Literature, film, photography, sculpture, and paintings were all entranced by the new possibilities of mechanical movement. Painters started portraying factory assembly lines and studying photography. Styles such as Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism tried to capture the speed of new machines and the repetitive nature of their action. One of the most prominent Futurists is the Italian artist Giacomo Balla, whose painting Speeding Automobile (1912) is a composition of purple and green surfaces that describes a car’s ability to speed rather than representing any actual car. The same artist painted in the same year a futurist version of a very recognizable dog. It’s a dachshund keeping up with his owner on a walk. Both the dog and the woman’s movements are signaled by the numerous feet going on like little cogs of a machine wheel. Even if the outlines of the dog are barely marked, there is no doubt that in this charming picture, here is a little sausage dog running as fast as his little legs can carry him.

Giacomo Balla. Dynamics of a Dog on a Leash, 1912. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Dog’s Soul

This is one of the most famous paintings by Goya, whose numerous works are already in a canon of art history (The Family of Carlos IV, Maya Nuda, The Third of May 1808). Goya lived long enough to witness many traumatic events such as the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, revolts, famines, and plagues. He also lost his hearing and fell out of royal favor. When he was in his seventies, he was living alone on the outskirts of Madrid, where he painted a series of frescoes (fifty years later transferred to canvas) that are collectively known as Black Paintings. These are not images for the faint-hearted: sarcastic, grotesque, creepy, pessimistic, and a bit mad. One of them is the most famous image of Saturn devouring his children, another one is a witch in a full trance, and yet another one is a macabre eating scene. The Drowning Dog comes from this series, and it is one of the most heart-breaking paintings ever. The little canine is almost entirely submerged in mud. There are no other elements to distract from his plight—no trees, no people—nothing to divert our gaze from his suffering. It may be an allegory of human suffering as well, but the dog is realistic and specific enough for us to feel empathy for this particular being.

The Drowning Dog. (Perro semihundido). Francisco Goya. 1820-23. Museo del Prado. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Goya painted this in an era when almost all paintings were either commissioned portraits of important people (royals, aristocrats, rich merchants, clergy), religious scenes—especially in Spain (think El Greco)—or paintings of historical and mythological themes. Images of animals were usually those of horses (to support a regal-looking man of action) or lap dogs, birds, and cats painted to make portraits of women and children cuter. And here comes a portrait of a dog that is really a symbol of misery, abandonment, and suffering.

So as not to leave you completely depressed by Goya’s desperate dog image, here is another psychological portrait of a single dog—this time, a majestic one and totally humanized. The 19th-century American painter Frederick Edwin Church almost exclusively painted landscapes. His enormous panoramas, like The Heart of the Andes and Icebergs: the North, were exhibited like cultural events with a 25-cent admission price. Even if Church’s fame has dimmed since his passing, his romantic views of majestic nature are in the canon of landscape art.

Oosisoak. Frederic Edwin Church. 1861. Private collection. Photo David C. Huntington at Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

When Church participated in 1860 in an expedition to the Arctic, he sketched glacial landscapes for his panoramas, but he also painted a unique oil painting. This is a portrait in the same sense you would have commissioned a portrait of a lord of a manor. This dog has not commissioned anything, but he probably posed, and he was painted with the same attention to detail and facial expression as if he were a person. Oosisoak was a sled dog belonging to Isaac Israel Hayes, an Arctic explorer, physician, and friend of the artist. The portrait apparently was painted in one two-hour sitting since even a patient dog has his limits. There are really no portraits in Church’s entire output—this is an exception. Oosisoak must have been really something special.