Food for the Soul: Lost Masterpieces. Part 3: Recovered

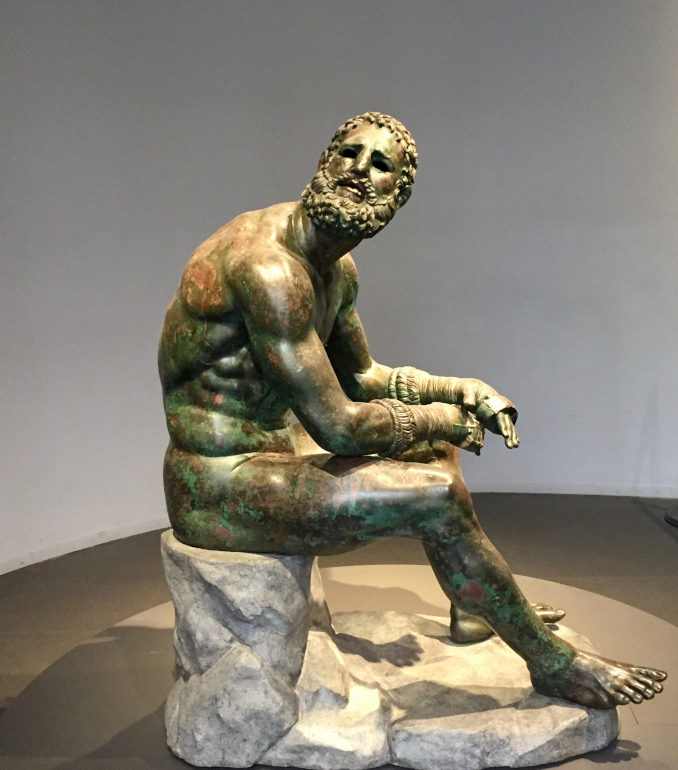

Boxer of the Quirinale. C. 330-50 BC. Palazzo Massimo alla Terme. Rome. Photo credit: Nina Heyn.

In the history of art, any recovery of a lost masterpiece is a happy event, but such events are more rare than an art loss.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Sometimes, there is hope for a lost work of art to reappear—even if it takes about 1500 years and countless generations to come back. Consider a bronze statue of a tired boxer, meticulously cast by a Greek artist sometime between 330 and 50 BC. It may have been a statue of a real fighter, with scars on his face, a boxer’s cauliflower ears, and the heavy expression of someone who just does not have the strength to get up again. Conversely, it may have been the artist’s vision of a generic “fighter” instead of a specific individual. Either way, the artist created it with extreme care and realism, joining eight different parts with invisible patching; using copper overlay on lips, nipples, and drops of blood; and adding a special tin alloy to indicate a bruise under the eye. The weariness of this scarred body comes across centuries later, regardless of the back story of the statue’s creation, now lost to time. Few full-size, early classical style bronzes survived from antiquity (the Riace Warriors in Sicily and the Artemision Poseidon being rare exceptions). This tired boxer not only is a masterpiece from this era but also an emotional portrait of a man’s suffering.

When this statue was dug out in Rome in 1885, it was found buried so deep that even the destruction of the nearby Baths of Constantine by Goths invading in the fifth century had not reached it. It was obviously carefully hidden from looters, and when it was finally excavated by the 19th-century archeologists, it looked as if the weary boxer had just been perched for a moment on a slope, waiting to be liberated from his earthly hideout. Someone who had not been able to protect his own life or that of his family managed to spare this bronze masterpiece from pillaging by a throng of barbarians.

Photograph taken by Rodolfo Lanciani on the 1885 discovery on the south slope of the Quirinal Hill in Rome. © Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte.

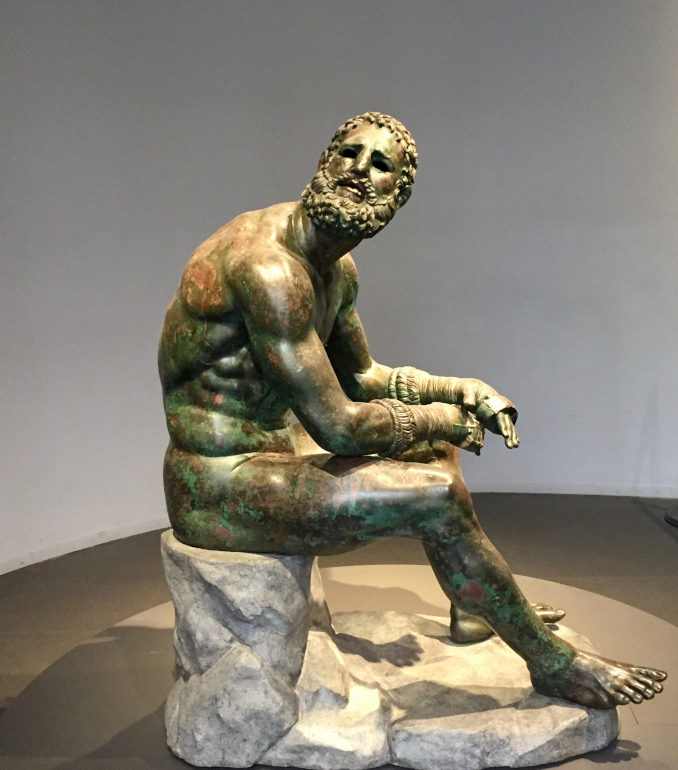

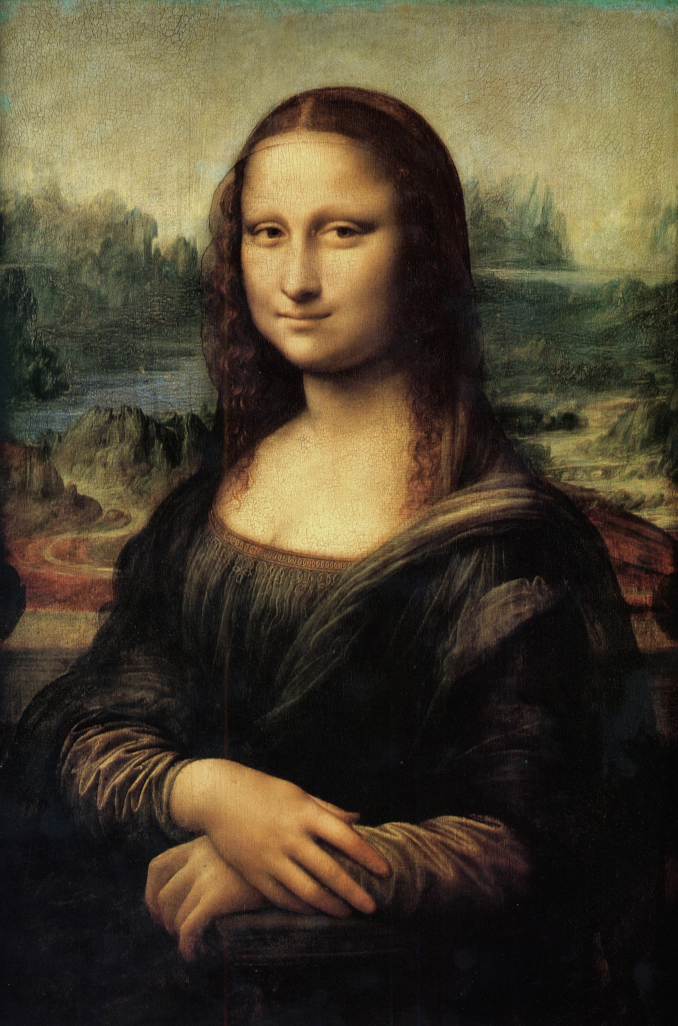

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing, as the early 20th-century theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre perhaps illustrates. The theft may have been an example of misplaced patriotism or else a clever way for a criminal mastermind to make use of the actual thief’s ignorance. In 1911, the whole world was shaken by the news that da Vinci’s Mona Lisa literally had disappeared from the Louvre. One morning, an artist walked in to do some sketching and discovered an empty wall; a nearby guard was not even aware of anything missing. The subsequent police inquiry was so sloppy that the detectives did not even make a connection between the recent placement of the painting in a glass casing and the possibility that one of the workmen could have been involved. Instead, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire was falsely accused and briefly imprisoned because he and Pablo Picasso had purchased some Iberian statuettes from Apollinaire’s assistant, not even aware that the statuettes were stolen from the Louvre. Picasso was scared of deportation and returned the art work as soon as he discovered the statuette’s origin. Apollinaire was soon released since it became clear that neither of them had been involved in the robbery.

Mona Lisa. Leonardo da Vinci (1503). The Louvre. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Two years later, when the painting was recovered, the perpetrator turned out to be an Italian carpenter named Vincenzo Peruggia who had worked on the picture’s casings. He kept it under his bed (dust! mice! bedbugs!) for two years and then took the portrait from Paris to Florence in his suitcase. He explained to the astonished directors of the Uffizi museum that he wanted to “return the painting to Italy.” Little did he know that Mona Lisa had never been in any Italian collection.

The fact is that da Vinci, toward the end of his life, grew tired of looking for a sponsor and decided to accept an invitation of the young and energetic French king François I. He made an arduous journey from Milan to Amboise, taking with him a few paintings, including this one. The king purchased the Mona Lisa for 4000 gold coins, and it entered the French royal collection in the early 16th century. By Napoleon’s time, the portrait had become celebrated enough that he insisted on moving it from the Louvre to his imperial bedroom.

The sensational 20th-century theft and unexpected recovery made the Mona Lisa a symbol of the Louvre, the epitome of fine art, and a pop culture icon, particularly after Kazimir Malevich painted Composition with Mona Lisa in 1914 and Marcel Duchamp added a moustache in 1915.

Later, there were also theories that the portrait was stolen to order, so that an entrepreneur could sell some previously prepared copies to private collectors. While this additional theory may have just been a literary embellishment in a 1930s book about the theft, the fact remains that the Mona Lisa affair remains a defining moment in the history of modern art robberies.

The last few decades abound with shocking stories of other museums robbed of their biggest treasures. Unfortunately, only some of these tabloid sensation stories end up with a recovery. One of them is the daring theft in 2000 of three incredibly valuable canvases from the National Museum in Stockholm. The crime team was led by a Russian mastermind who engineered the best alibi ever by staying in a low-security prison while his heist was executed. The actual robbery was done by a trio of Bulgarian and Iraqi men who blocked street access to the museum with burning cars and metal spikes, committed the heist at gunpoint, and then escaped by boat from the waterfront outside the museum. The robbery list was prepared as carefully as the heist plan; the canvases taken included Rembrandt’s self-portrait (painted when he was 24 years old and just on the cusp of his most powerful artistic period), and Renoir’s two beautiful “close-up” portraits called Young Parisian and Conversation.

Conversation. Pierre Auguste Renoir (1879). National Museum Stockholm. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Conversation was recovered in Stockholm and Young Parisian was found all the way in Los Angeles during a drug raid. Getting back the Rembrandt took five years, however. The recovery involved a sting operation of Swedish and Danish police, stalking the suspects, blackmail of a robber’s father, an FBI agent posing as a dealer for a wealthy collector, and an impromptu black light test (a real painting—painted on copper and never retouched—should not show any luminescence).

Self-Portrait. Rembrandt (1630). National Museum Stockholm. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Sometimes, things that are missing … are not really lost. What is harder is to prove that the newly rediscovered treasure is authentic. Da Vinci’s drawing La Bella Principessa was only deemed an authentic portrait of Bianca Sforza after it was finally matched to the Sforza family album at the National Library of Poland in Warsaw. The search for the drawing’s provenance (the artwork was originally sold at auctions as a “19th-century German imitation of Italian Renaissance”) took years, and its authorship is still disputed even though this exquisite drawing has had champions among the leading Leonardo specialists.

La Bella Principessa. Leonardo da Vinci (1496). Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

A beautiful and very spiritual Caravaggio painting called The Taking of Christ was believed lost—and when found, it struggled for recognition. Caravaggio painted this canvas in 1602 as a commission for a Roman patron named Mattei. The painting stayed in the family, but at some point it got misattributed as a canvas by Gerrit von Honthorst, a known Dutch follower of the Caravaggio style. Exactly two hundred years later, the family sold this “Dutch artwork” to a Scottish collector. The painting ended up as a donation to Jesuits in Dublin, and only in the 1990s did it finally get a good look from a professional art historian. Sergio Benedetti was Italian, and a curator at the National Gallery in Ireland, so he knew a thing or two about paintings in general and about Caravaggio, in particular. After restoration, the canvas revealed not only its lost colors but also the hand of its true author.

The Taking of Christ. Caravaggio (c. 1602). National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

This painting depicts an action scene. Farthest on the left is St. John, who is in a panic, his cloak flying and arms outstretched, trying to run away from a soldier who has already grasped his cloak. Judas is kissing Jesus to identify him to the soldiers. Finally, there is a man holding a lantern, believed to be Caravaggio’s self-portrait. The reflective armor of the soldier’s arm in the center of the picture can be interpreted as a mirror that reminds viewers of their own betrayals of the teachings of Christ. The linear composition forces the viewer’s eye to follow events like in a film clip; the splashes of color jump out of darkness to accentuate each character’s story.

There are numerous copies of this Caravaggio painting, some made as early as the 17th century, and there is even one version from Florence that at some point was believed to be an original. However, paint tests pointed to its later creation. Because the list of recognized works by Caravaggio is limited (and not really determined—between 50 to 80), any work of his that can be found and attributed to him is a gain for fans of this theatrical and spiritual art.