Food For the Soul: Artists Gardens

Strange Garden (Dziwny Ogród). Józef Mehoffer (1903). National Museum, Warsaw. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

There are very few advantages of a global lockdown other than decreased pollution, but perhaps one of them is our renewed appreciation of gardens. A lot of us have favorite gardens. It might be a garden in a historic park or museum, a nearby city square, or maybe just a memory of a garden of our youth. Painters also have their favorites, though not necessarily real ones—or at least not perceived realistically when they end up on canvas or are constructed.

Sometimes, a garden is just a setting for a scene, as it is in Alexander Gierymski’s nostalgic painting entitled In the Arbour. Gierymski, a 19th century Polish painter whose canvases are now among the most prized treasures of the National Museum in Warsaw, struggled most of his life for recognition. In some ways, his life story resembles that of van Gogh; Gierymski spent years outside his native country, experienced poverty and a lack of critical recognition, and died in an asylum. None of this is reflected in this sunny picture, where he imagines life in the 18th century. Guests are chatting animatedly at tables set in a garden, sunlight is streaming through the arbor’s slats, and you can almost hear water trickling in a fountain. This is an idealized rococo world of elegant silks, witty conversation, and leisurely life—a happy moment in a sunny garden of fantasy. Gierymski’s other famous paintings are different—realistic scenes depicting the life of the poorest residents of Warsaw’s riverside. This one, however, is all about Impressionist light in an idealized world of a carefree past.

In the Arbour (W altanie). Alexander Gierymski (1882). National Museum, Warsaw. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Common

Claude Monet created the mother of all gardens at his Giverny residence, spending decades planning, building, and painting his idea of an earthly paradise. What started small as a flower patch near the summer rental house ended up as a pond, acres of flowers, and monumental paintings of water lilies that are 55 feet (17 meters) long. Monet, whose Impression: Sunrise launched the whole movement’s name and fame, was originally interested in the concept of plein air painting (as opposed to sketching a landscape outside and completing the finished painting in a studio) to capture the effects of light and color. His observations of those changes are evident in his 1890s series focusing on the Rouen cathedral or haystacks, but as early as the 1880s, Monet was already exploring the concept of the same place painted in different ways. He examined the abundance of color and light offered by a garden path in two paintings called The Artist Garden at Vétheuil. One painting (shown here) featured his son Michel and his future stepson Jean-Pierre, while the other one was empty of figures but still represented a study of morning sun on a garden path. The garden at Vétheuil was a rental that Monet was allowed to remodel for his artistic purposes. For instance, the porcelain flower pots were brought by the artist for the picture, and even though in reality they would have been a traditional blue, their pattern is more greenish-grey due to shadows. So, this is an image of a real garden—but painted the way an artist would stage it and see it.

The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil. Claude Monet (1880). National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Sometimes what an artist needs is just bright light and a good landscape. Compare two paintings by van Gogh. One was painted in the town of Nuenen in The Netherlands. It is an early van Gogh, before he found his artistic language. The artist spent about two years living with his parents (after a couple of stabs at a professional life as a missionary and an art dealer had already fizzled), and it was during this period that he painted his first big oil painting, the famous work called The Potato Eaters. In The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen, the painting shows a dark, greenish-brown image of empty vegetable patches and anemic leaves on trees. Apparently, this was painted in May—if so, this is hardly an inspiring view of nature during one of the best months of the year. (Incidentally, this drab but historically important painting was just stolen in March from an exhibition that was temporarily closed due to coronavirus.)

The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen. Vincent van Gogh (1884). Stolen from Groningen Museum, The Netherlands. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons

Within a few years of painting Nuenen in several sketches and oils, van Gogh became a full-time painter and moved to Paris and then to the south of France. At that point, there was no holding him back in terms of color and joy at finding exuberant nature on display in warmer climates. Here is a van Gogh painting from Paris. Today, Montmartre is a hilly neighborhood in the middle of the city, and only the famous windmill of the Moulin Rouge cabaret reminds people that, 150 years ago, it was farmland. Van Gogh captured this view of the Paris outskirts at the last possible moment—soon after factories and houses had started taking over Montmartre’s vegetable plots and fields. This canvas is not yet on a par with the sun-drenched Arles of yellow houses, violet irises, and turquoise water, but even a Paris suburb was better for this artist than a cloudy landscape in his native land. Van Gogh always loved gardens, but he just needed the right ones to paint.

Kitchen Gardens in Montmartre. Vincent van Gogh (1887). Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

You could say that Salvador Dalí had two passions in life: surrealism and his wife Gala. The first resulted in his never-ending fountain of creativity, which gave the world melting watches and long-legged monsters on alien beaches. The second was his muse, pampered and adored and made mistress of the Castle of Púbol in Catalonia. Dalí purchased this old medieval and ruined castle in 1969 and made it his wife’s sanctuary (he famously promised never to visit it without her permission—how many husbands would create such a private space for their spouses?). His remodel included creating a Dalí-style garden, replete with fantastic creatures that were inspired by the Italian Gardens of Bomarzo.

Fury. Bomarzo Garden (Parco dei Mostri), Italy. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

The “park of monsters” in central Italy that inspired Dalí was commissioned in the 16th century by prince Pier Orsini to commemorate the death of his wife Giulia. This Mannerist-style “enchanted garden,” full of stone monsters, was largely forgotten until Dalí made a short film about it and used the monster ideas in his paintings. He painted The Temptation of St. Anthony, his suitably surreal version of a saint being tempted in a desert, as an entry for an art competition. Though he lost to Max Ernst—and never participated in any art contest again—this painting remains one of the most iconic Dalí images. The long-legged elephant from that painting is inspired by Bomarzo monsters, and it appears in sculpted form in Dalí’s own garden at Púbol. There, an elephant with camel’s legs, large and hidden in the foliage, is a perfect Dalí creation. The elephant is carrying another creature on its back—a heraldry eagle—which is probably a reference to Dalí’s coat of arms as Marquess of Dalí de Púbol.

Elephant at Castle de Púbol. Salvador Dalí. Photo: Albert G. Rovi Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

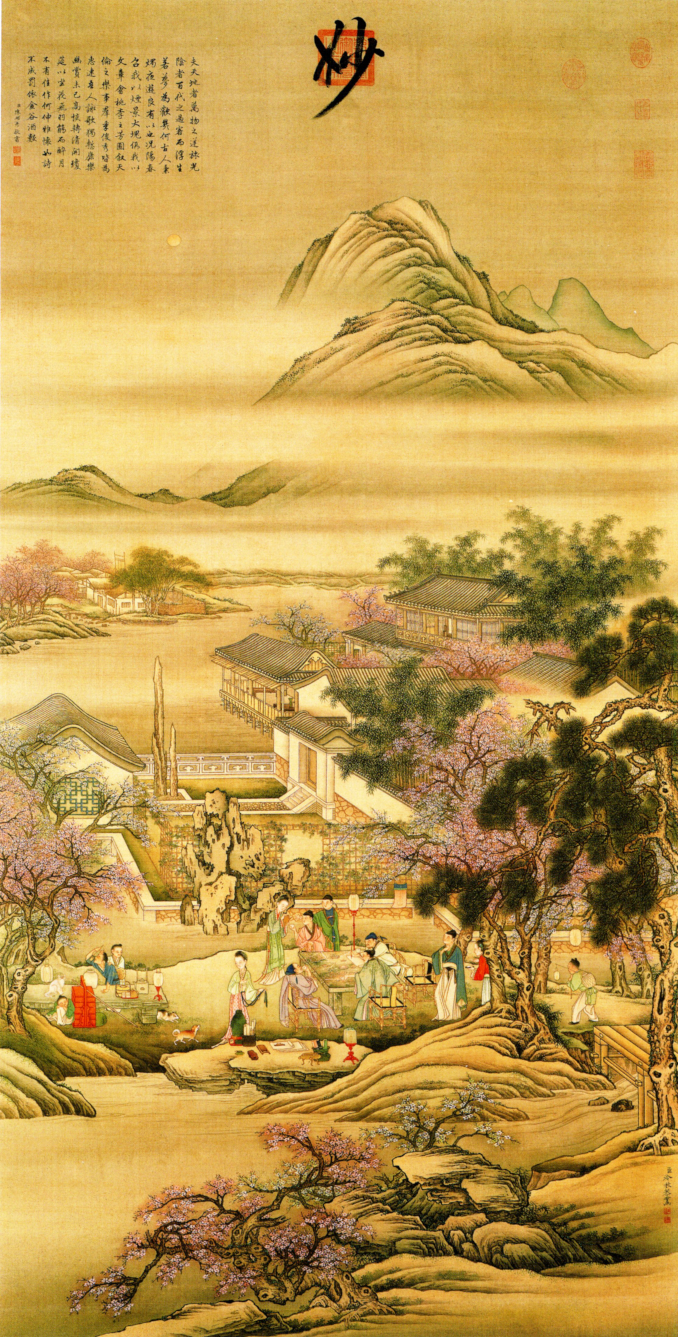

A garden scene entitled The Spring Evening Banquet in the Peach and Pear Blossom Garden was painted by Leng Mei (an early Qing dynasty painter) in the same century as Orsini’s monster gardens but is entirely different in its approach to what a garden should be. For millennia, Chinese gardens (the real ones and the painted ones) have been designed as places of beauty, respite, and harmony between rocks, plants, and people. And while Chinese landscape art is guided by different principles than the Western version, any viewer can experience the calm that emanates from this contemplative picture.

The Spring Evening Banquet in the Peach and Pear Blossom Garden. Leng Mei (between 1677-1742). National Palace Museum, Taipei. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons.

Leng Mei, an artist who served three different emperors, painted a famous series of illustrations on farming and weaving. He also specialized in elegant paintings of court ladies. Leng and other court painters were trained by Chinese masters but also by Giuseppe Castiglione, a Jesuit artist residing at the emperor’s court. This perhaps accounts for the eye-pleasing perspective and vanishing point composition, but the garden is all Chinese—well-trimmed trees carefully arranged among natural rocks and augmented by added rock features, with buildings that melt into the landscape in a harmonious way. The garden is sheltered by a distant mountain that provides proper feng-shui for the garden grounds. As sumptuous as court gardens must have been, however, this looks like an idealized space, and especially one that illustrates a famous garden poem by the wandering poet from the Tang dynasty, Li Bai.

If we cannot travel to real gardens, we can at least visit the strange, beautiful, or fantastical gardens of artists’ minds.