Food for the Soul: Good and Bad Government

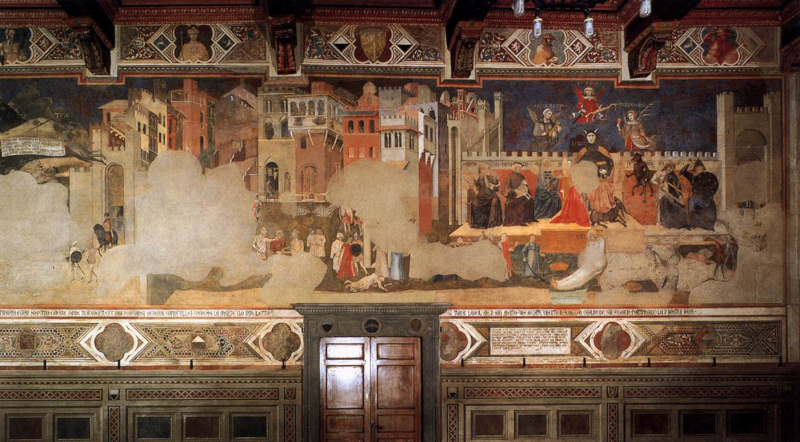

Effects of Good Government in the City. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

The United States is preparing for the November 3rd presidential election amid the most polarized debate in living memory about what is right and wrong and what kind of government the voters will get as a result of this election.

It may be a good moment to take a look at a famous and incredibly beautiful fresco from Siena. It is not a new idea that responsible and humane management may have something to do with the quality of life of the citizens who are being governed. In 1338, the councilors of the city-state of Siena commissioned a fresco for their city hall from Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Ambrogio and his older brother Pietro were Sienese artists famous for their religious paintings, but this was an entirely secular theme to tackle.

Fourteenth-century Siena was a banking center in the middle of prosperous Tuscany. The rotating council called “the Nine” would plow the city’s banking profits into public works, financial programs, and artistic endeavors that supported the policy of corporate responsibility, intelligent governance, and financial management. With the commissioned fresco, they wanted to illustrate in a public space the idea that a citizen can be productive and supportive of the government if he lives in a well-run state.

Lorenzetti not only provided entire walls covered with beautifully rendered scenes that exemplify these social tenets but also created a masterpiece of landscape painting. It was exceptional for his times. Landscapes did not really take off as stand-alone subjects of art until the start of the 16th century. During Lorenzetti’s time, landscapes were usually seen as background for manuscripts or “space fillers” for portraits or religious paintings. Ambrogio’s work stands out as an unusual-for-the-time, large-scale landscape, and it includes an even rarer picture of a cityscape.

The frescoes were designed as a panorama of both the Tuscan countryside and Siena’s buildings, some of which are still recognizable today. Against this solidly realistic background, the artist presented the Sienese with two versions of their potential future. The positive outcomes are expressed in Effects of Good Government in the City, Effects of Good Government in the Country, and Allegory of Good Government. While the titles of the scenes are contemporary, they accurately reflect the ideas presented in them.

The city scene is bustling with activity. A farmer has brought his flock to sell, and at a cobbler’s stall, a customer has come about his shoes while his well-fed donkey stands obediently behind him like a faithful pet. New construction in the background is almost finished, with the final roof tiles being laid. Wherever you look, the town is bustling. The buildings are painted in bright contrasting colors (a similar color trick that contemporary builders use to enliven rows of townhouses in American suburbia). The center square is occupied by young women, possibly muses, dancing—a perfect metaphor illustrating that in prosperous and peaceful times, the arts flourish as well.

The country scene presents the same well-ordered, soothing vision: fields and gardens being tended, hills dotted with even rows of grapevines, and travelers moving unhurriedly through an obviously safe countryside. The figure of Security proclaims above: “Without fear every many may travel freely and each may till and sow, so long as this commune shall maintain this lady sovereign, for she has stripped the wicked of all power.”

Effects of Good Government in the Country. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Finally, Allegory of Good Government sums up the message that justice and peace, supported by wisdom, are necessary for good governance. On the left, there is an important figure of Justice, who is looking toward Wisdom for counsel. She is accompanied by personifications of virtues (Fortitude, Prudence, Temperance, Peace, and Magnanimity) that are also necessary for good government.

Allegory of Good Government. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

No didactic discourse would be complete without presenting the negative outcomes. On the opposite side of the hall, Lorenzetti painted mirror visions of bad quality of life.

Effects of Bad Government in the City. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The Effects of Bad Government in the City fresco is damaged, but you can still see that the buildings are empty or in disrepair, and the bustling commercial activity is gone. In the same way that in Good Government the city was presided over by a ruler identified as the personification of the Commune of Siena, the bad government also has a ruler—a Tyrant. His portrait is sufficiently scary to imbue children with fright:

The Tyrant. Detail of Effects of Bad Government in the Country. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Instead of having Peace, Faith, Hope, and Charity to guide him—the helpmates of the ruler on the “good side” of the hall—the Tyrant’s companions are Vainglory, Avarice, Pride, Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War. Ambrogio must have seen it all. You could not live in the 14th-century world without having experienced constant military conflicts, corruption, and unchecked feudal power.

Effects of Bad Government in the Country. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1339). Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Much has been said about the frescoes not being painted to scale—the sizes of the figures are not in proportion to the buildings when you look at them straight. There is, however, an optimal vantage point in the room where the frescoes are situated. The composition looks best if you place yourself underneath the figure of Justice and near the door through which the Sienese councilors would have entered for their meetings. Lorenzetti designed his panorama for people to move along the walls, peering at details, taking in all the scenes of daily life, deciphering allegories, and reading moralizing messages. The councilors were expected to use Justice’s point of view to see the whole land in the correct perspective.

Beautifully designed and rendered, the message for the councilors was simple: do the job right, with people’s welfare in mind, and this is what our city will look like. If you don’t, the alternative is frightening.

The Lorenzetti brothers did not live long. Pietro and Ambrogio perished in 1348 during the plague that wiped out a large portion of Europe. However, Ambrogio’s vision of good political decisions can still be admired at the Siena City Hall.

Siena Palazzo Pubblico (City Hall). Siena, Italy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain