Food for the Soul – Women at Work Part I – Masterpieces

Birth of the Virgin. Domenico Ghirlandaio (1479-85). Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

The majority of figures in paintings, especially those created before the 20th century, are male. The paintings show men heroically fighting or representing religious or mythological figures, men hunting, or men suffering the toil of existence. Women appear mostly as Madonnas or saints, sometimes as mythological figures, in formal portraits for sitters’ salons, or as nudes for private viewing. However, this is a series on women doing something else—what the majority of them were doing all these centuries: working.

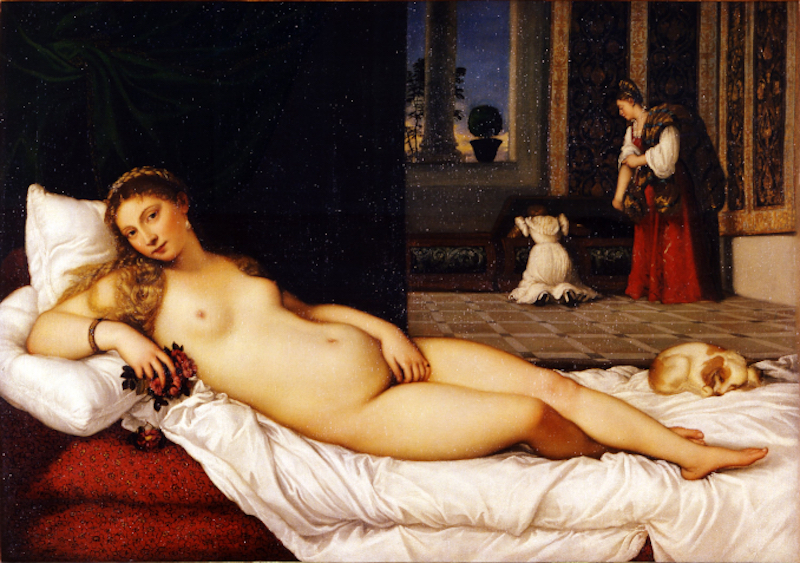

Some mythological and religious scenes are famous for what is presented in the main part of the picture (for example, Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Ghirlandaio’s Birth of the Virgin), but in this series on women at work, we shall ignore the main image in favor of what happens on the periphery. This can be an apt metaphor for women’s work in general, because often women’s housework or even their professional achievements remain unsung—if not downright taken for granted.

The painting above is one of the masterpieces of the Florentine Renaissance. Domenico Ghirlandaio had already decorated the most prestigious buildings of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican and Palazzo Vecchio in Florence when, in 1486, he was commissioned to paint a fresco cycle, including the Birth of the Virgin for a family chapel of Giovanni Tornabuoni. The center of this composition is taken up by Tornabuoni’s daughter Ludovica, dressed in a golden brocade gown and surrounded by her equally sumptuously dressed companions, one of whom is looking at us rather than at baby Mary. Ludovica is standing stiffly in her formal dress, looking at Mary’s young mother Anne, who is resting after the birth. As beautiful as St. Anne is, however, the viewer’s eye is more drawn toward a figure below—a young servant who is graciously leaning to pour bath water. Ghirlandaio’s sketch of this servant has survived to the present day, which is how we know how carefully he planned the folds of the yellow garment and the bent-forward pose. Because women gave birth at home and would typically be attended by their female friends, relatives, and servants, such a domestic scene would not have been unusual. Ghirlandaio takes this domestic setting but decorates the room in a most ornate frame of carved columns and a frieze of cherubs, populating the tableau with his patron’s family. However, the most gracious figure in the fresco is not the noble Ludovica but the lowly but graceful servant.

The Birth of the Virgin. Francisco de Zurbarán (1629). Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Baroque artist Francisco de Zurbarán also undertook the popular theme of Mary’s birth. Zurbarán was nicknamed the “Spanish Caravaggio” due to his mastery of light and shadow as well as a large body of religious paintings. He had many commissions from monasteries for painted altarpieces, and he was a favorite painter of King Philip IV. Though famous for his mastery in painting folds of white fabrics (resulting in many commissions from Capuchin monks), he was also a master of color. His Birth of the Virgin is a canvas where strong primary reds, yellows, and blues are arranged in an oval around the figures of women. Like Ghirlandaio, Zurbarán featured the commissioning donor prominently—an aristocratic lady dressed in the latest fashion. Unlike Ghirlandaio, Zurbarán was much more realistic about the birth process (he married three times and had several daughters); his St. Anne looks exhausted and definitely in need of the restorative broth proffered by attentive servants. I particularly like the image of an old midwife—a woman without whose assistance many a birth would have ended in tragedy. This working woman would not have been much acknowledged by aristocratic clients like the lady in the yellow gown, yet the artist placed her in the center of his canvas. She is the one who helped bring baby Mary into the world.

The Spinners or The Fable of Arachne (Las Hilanderas). Diego Velázquez (1644). The Prado, Madrid. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Together with Las Meninas, The Spinners belongs to the canon of Velázquez’s greatest masterpieces; it is impossible to do it justice in barely a few sentences. The painting is a retelling of the myth of Ariadne, the young and talented weaver who dares to create a tapestry showing the loves of gods, thereby incurring the wrath of Athena (Minerva). When the proud weaver realizes her mistake, she hangs herself in anguish, but Athena transforms her into a spider, a creature condemned to incessant weaving. Velázquez presents both moments from the story; in the foreground, Athena is disguised as an old woman spinning alongside Ariadne, while in the next room, the goddess of war is revealed as Pallas Athena who berates the hapless spinner. In the 18th and 19th centuries, this canvas was often thought to be just a scene depicting the manufacture of tapestries (possibly based on the Royal Tapestry Factory of St. Elizabeth in Madrid), and this is why it is entitled The Spinners. Mythological interpretations became popular later and although they are now firmly established, for the purpose of our working women theme, let’s look at the women simply as weavers.

By Velázquez’s time, tapestry had had centuries of recognition as a form of artistic expression just as noble and precious as paintings. The tapestry in the back room of The Spinners is actually based on Titian’s Rape of Europa because Velázquez is contrasting here the high art of tapestry in the back room with the simple craft of spinning wool that takes place in the front. However, we can also look at the front room’s scene as a portrait of real weavers at work. The hard-working spinners are working barefoot—even the goddess who is disguised as an old woman. You feel the warmth of the room, the wheel spinning, and the kitty playing with a wool ball. For all its mythological and sophisticated theme, this is an intimate scene of women busy at a task that requires skill, speed, and concentration.

Venus of Urbino. Titian (1538). L’Uffizi, Florence. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Despite occasional lustful glances by contemporary tourists visiting L’Uffizi museum in Florence, Titian’s Venus of Urbino was not meant to simply titillate but to portray marital love. The small spaniel and the myrtle and roses are symbols of faithfulness and constant love. The painting was commissioned in 1538 by Guidobaldo II della Rovere (who soon afterward became the Duke of Urbino) for his bridal chamber. Since then, it has become one of the most popular canvases in all of Italy and art history. The painting, itself inspired by Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, was famously referenced three centuries later in Manet’s Olympia. It has been studied for its compositional mastery for ages. However, if we ignore the heroine of this picture for the moment, we notice two other women—perhaps a maid and a lady-in-waiting who are searching for their mistress’s gown. The maid, who is rummaging in a chest (no walk-in-closets with racks in those times), is supervised by a woman in red who is already holding a gold and green gown as perhaps the first choice. Even if Venus herself is preoccupied with just looking gorgeous, the household is busy keeping her in style—clothes have to be prepared for the mistress of the house. With the clean floor and a plant that presumably has been watered, it is clear that this beautiful palace (an actual view of Urbino’s residence) was well taken care of by women such as the two figures in the background.

The Last Supper. Tintoretto (1594). St. Giorgio Maggiore, Venice. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Tintoretto, born in the year of da Vinci’s death, represented a new era of European culture. The calm and elegant style of the High Renaissance gave way to mannerism and the religious fervor of the Church opposing the Reformation. Intimate religious pictures gave way to monumental canvases. Tintoretto, who by age 20 was already so accomplished that apparently a jealous Titian released him from apprenticeship, lived long enough to participate in this artistic and intellectual shift. Over the last 20 years of his life, his painting style changed from lighter and more colorful works to darker pictures enlivened by just a few points of light and splashes of color. He painted The Last Supper in the last year of his life—the culmination of his skill and style. This Last Supper is so different from da Vinci’s orderly, symmetrical composition. Here, the table is placed at a rising diagonal, while the ceiling is populated by ghostly swirls of angels. There are only two sharp light sources: a lamp that symbolizes divine spirit and a shining halo over Christ’s head. The light shines over the stretched-out arms of a servant who is reaching toward the basket. In this painting, the supernatural elements of divine and angelic presence mix with the mundane activity of a group’s mealtime. Women are serving food, a cat is trying to climb into a basket, and the apostles look like typical Venetian youths of the 16th century. No matter how exalted and spiritual an event this is, life has to go on—and women are working hard to feed the diners.

Even old masters did not create their paintings in an artistic vacuum. They looked at people around them to capture their faces, gestures, and tasks. This is how we get these little glimpses of hard-working women, tucked somewhere in dramatic tableaux and telling us real-life stories.