Food for the Soul: Hilma af Klint, the first abstractionist. Women Artists Series 5

Hilma af Klint. Self-Portrait, date of painting unknown. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

The fact that painter Hilma af Klint has been unknown in the history of modern art is not that surprising. That even now she remains unknown is a bit more controversial.

There are several reasons for Hilma’s artistic obscurity, including in her native Sweden. During her active years in the early part of the 20th century, she exhibited only once, and most of her artwork was kept in storage not just during her lifetime but for decades afterwards. As a woman and a spiritualist, she was also shunned by mainstream art and cultural authorities. She remains relatively unknown because almost all her important paintings are kept together by her family foundation, outside any major museums. In other words—since her paintings aren’t owned by any modern art museums and are not available for purchase by collectors, Hilma’s art remains obscure even though studying her art would revise the history of art entirely.

Hilma af Klint. Group IX SUW, The Swan No. 9, 1915. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Rhododendrites via Wikimedia Commons

If you ask art historians about abstract art, they will often point to Wassily Kandinsky and 1911 as the pivotal year when this artist shifted from modern but figurative paintings (such as paintings of a horse or a comet) to images that were devoid of recognizable depictions. The color and line compositions that Kandinsky is so famous for immediately inspired scores of artists and schools, such as the Italian Futurists, French Cubists, and, well, all abstractionists. In 1935, Kandinsky wrote about his (lost) 1911 abstract painting: “Indeed, it’s the world’s first ever abstract picture, because back then not one single painter was painting in an abstract style. A ‘historic painting,’ in other words.” Smart lawyer that he was, he must have wanted to record his place in art history as the first abstractionist ever. Except that he wasn’t.

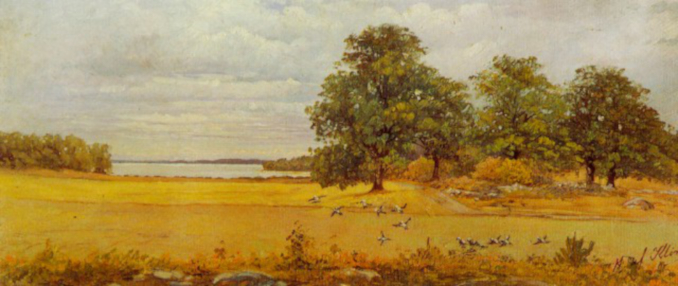

Hilma, living quietly in the backwater of European art centers went from this in 1903:

Hilma af Klint. Late Summer, 1903. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

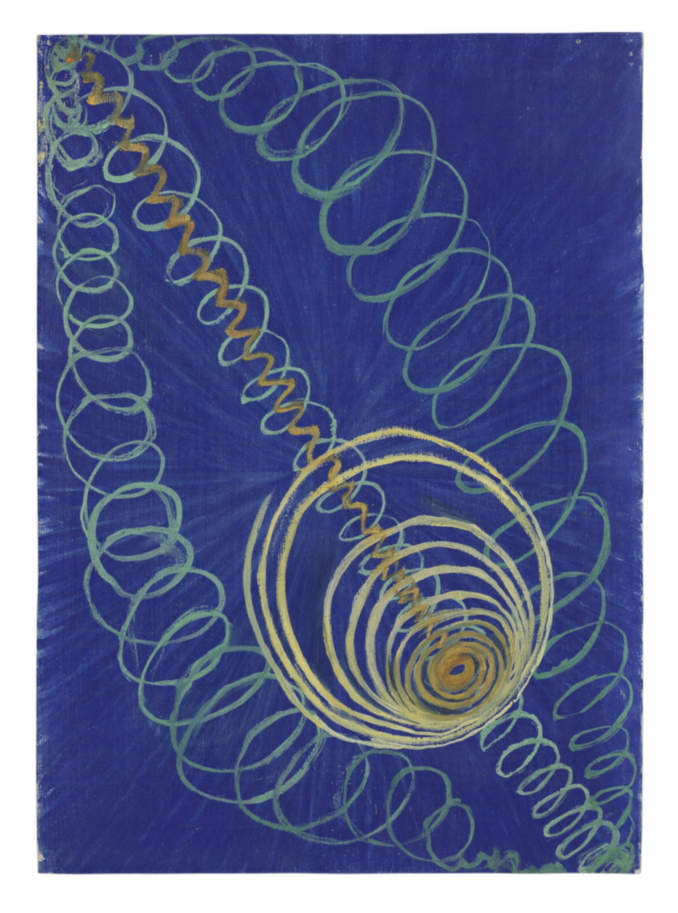

To this, three years later:

Hilma af Klint. Primordial Chaos, No. 16. From The WU/ROSEN Series. Group 1, 1906-1907. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet, Wikimedia Commons

What happened? Hilma was inspired by her study of theosophy and by the writings of Madame Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner. This was a popular spiritual direction for educated female seekers at the end of the 19th century. Theosophy and similar movements of the time provided an outlet for women seeking paths to spiritual growth not offered by traditional religions. Medium séances and theosophical study were popular all over Europe and America. But Hilma went beyond treating these interests as a fashionable pastime. In her own words, recorded in hundreds of meticulously kept notebooks, her spiritual studies led her to an opening of enormous creativity. She channeled her mystic experiences into complex abstract paintings in a place and time that had not seen anything like them before: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

Hilma af Klint. The Swans, 1914. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

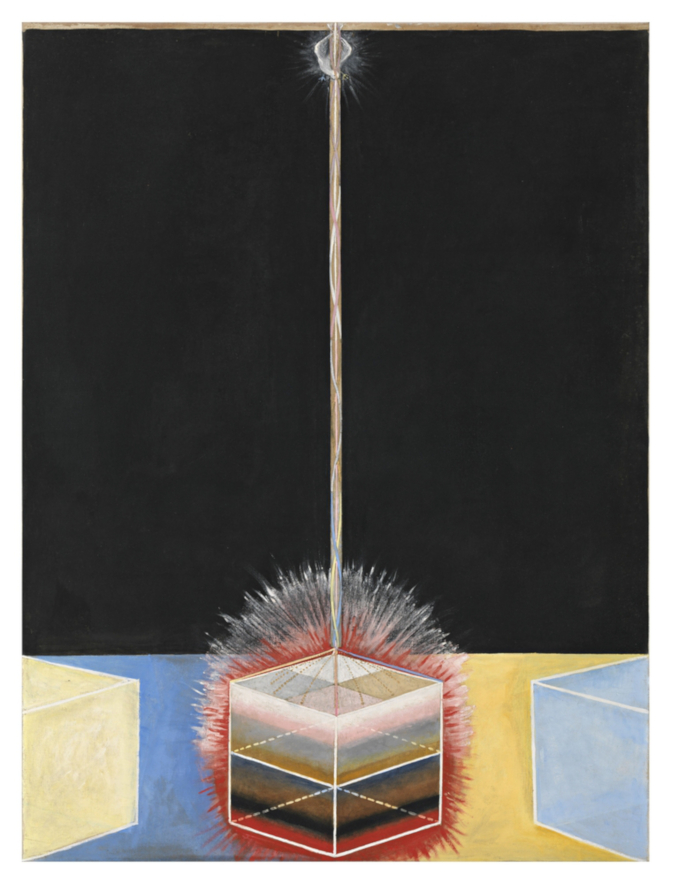

Like many artists, from Monet to Picasso, Hilma painted in series. Her earliest and most impressive was the cycle of large-scale Paintings for the Temple Decorations that included ten large works and another 183 paintings that were to represent, in an abstract form, “immortal aspects of man.” While this remains her most important work of the period until 1915, she also produced other cycles including Primordial Chaos, a blue abstract series, and many paintings of swans—from some more or less realistic (albeit conceptually positioned) to complete abstractions such as the one below.

Hilma af Klint. The Swan No. 18, 1915. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Hilma came from a family that traditionally provided Sweden with many naval captains and admirals, so the precocious girl grew up in the world of precise lines and shapes of numerous naval maps as well as a scientific approach to information. She perfected her drawing skills at the Royal Academy in Stockholm, where she forged lifelong friendships with women artists who would later support her creative path. After graduation in 1877, she spent a few years painting traditional portraits and florals—the nature and anatomical illustrations are masterfully precise. One of her paintings from this era was sold to the Louvre, leaving no doubt that she could have continued on the respectable and profitable path of a professional portraitist and nature illustrator. Her restless mind led her first to detailed studies of nature (she wrote in her notebooks of her plans to catalog all the Swedish water flora and fauna, moving on to trees and wood creatures), and then to her more profound studies on the origins of human consciousness.

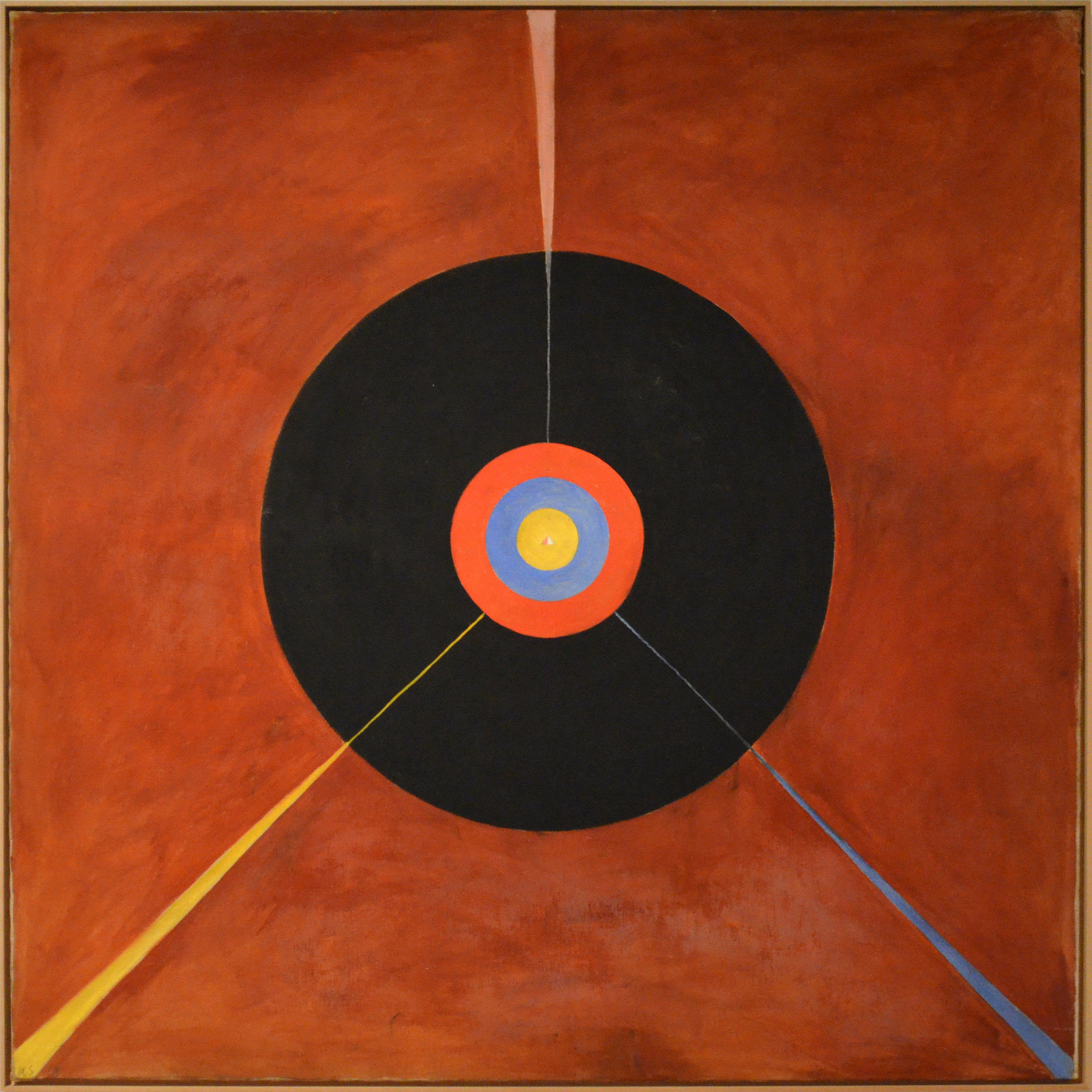

Hilma af Klint. The Dove, No. 3, Group IX/UW, The SUW/UW Series, 1915. Oil on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet, Wikimedia Commons.

The turn of the last century was an age of shocking and revolutionary discoveries—radioactivity, the atom, the theory of relativity, genetics. For a curious and bold mind, these discoveries upended all the then-prevailing ideas about the surrounding reality and raised new questions. For example, if most of the world is invisible, how do you show this invisible play of forces of light, rays, waves, and particles? What is soul? What is spirit? How are things interconnected? Are humans, plants, and earth elements all just expressions of the same matter? These questions lay at the foundation of Hilma’s images, which were truly like nothing ever before invented in fine art.

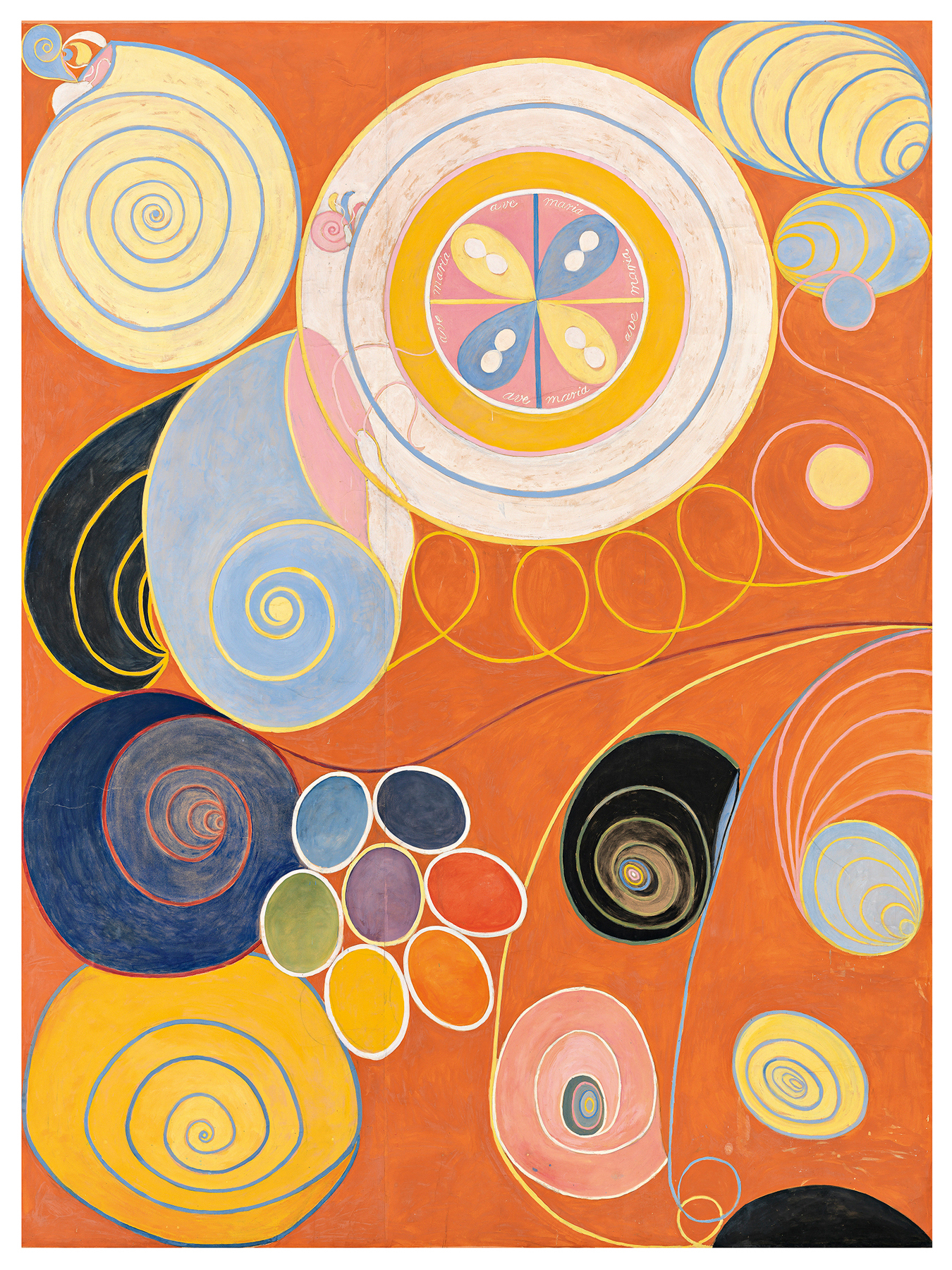

Hilma af Klint. The Ten Largest No. 3 – Youth, 1907. Tempera on paper, mounted on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Between 1906 and 1907, Hilma painted 10 large-scale paintings; the paper sheets are approximately 10 feet by 8 feet (320 x 240 cm). She used oil and tempera paints that held their vivid oranges and blues extremely well. These images, which she called “the key to all works,” were a result of séances where a spirit guide directed her to create them as decorations for a theosophical temple. They were intended to express insights about human development and the holistic view of interconnectivity. The New Age ideas of the 20th century may be old hat to us now, but at the dawn of that century, Hilma must have had a lot of artistic conviction to express these unconventional ideas in her bold, huge paintings. Today, we would call them “psychedelic,” but what could they have been named decades before the hippie era? The world around Hilma—especially in austere, Protestant Sweden—was Victorian: conventional, tangible, realistic. Her paintings were nothing of the sort.

Hilma af Klint. The Ten Largest No. 2 – Childhood, 1907. Tempera on paper, mounted on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The tragedy for both Hilma and art history is that her pioneering creativity was never recognized during her lifetime. She exhibited just once (or possibly twice), despite her numerous attempts to connect with gallerists, artists, and thinkers outside Sweden. A recent theory suggests that photographs of her abstract paintings (painted between 1906 and 1910) were shown to Wassily Kandinsky, whose own artistic evolution moved, from 1911 on, to this kind of purely abstract imagery. So. . . maybe he was not entirely unaware of the abstract revelations of this woman living in a city far away from the artistic center of Paris? Hilma tried unsuccessfully to popularize her art and her theosophical insights, but as a woman artist and someone who dared to proclaim her spiritualism as a source of inspiration, she was not taken very seriously. Eventually, she locked up all of her art and stipulated in her will that the paintings were not to be exhibited for 20 years, leaving about 1300 artworks and notebooks locked in a family attic for decades. Only recently did her descendants start bringing her art out into the limelight, including an exhibition in Los Angeles in 1986. An exhibition in Stockholm drew over a million visitors. Some international museums like the Tate have shown her work, and the Guggenheim museum exhibited her work in 2018.

Hilma af Klint exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in 2018. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Ryan Dickey, Wikimedia Commons

For the most part, however, Hilma’s inspired, colorful, holistic images remain unknown, and she is non-existent in textbooks on modern art or in anthologies of abstract artists—even if she was literally the first one.

Hilma af Klint. The Large Figure Paintings, nr 5, The Key to All Works to Date, Group III, The WU/Rosen Series, 1907. Tempera on paper, mounted on canvas. Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Albin Dahlström/ Moderna Museet, Wikimedia Commons