Food for the Soul: Calder-Picasso. Back to Museums Part 1

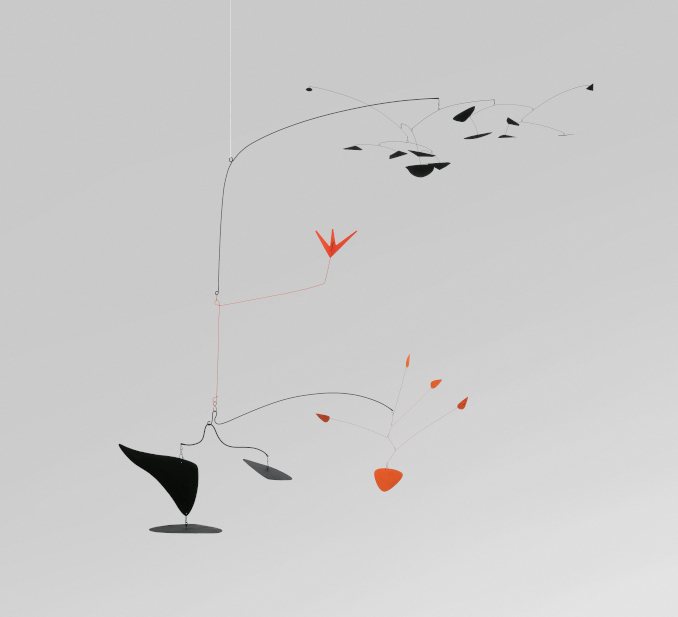

In the center: Alexander Calder. Untitled (mobile-1956) and Untitled (painting-1967). Calder Foundation New York. Photo: Installation view of “Calder-Picasso” at the de Young Museum, photography by Gary Sexton. © 2021 Calder Foundation New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

I’m celebrating the reopening of California’s museums after a year-long hiatus with a report from one of my favorite museums: the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The de Young has launched its reopening with an exhibition that explores affinities and differences between Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). The exhibition was originally created and curated by the grandsons of the two artists, Alexander S.C. Rower and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso.

Even if Picasso was older than Calder by 17 years, biographically the two artists had things in common. They were both Paris transplants (Picasso was a Spaniard and Calder an American), and both loved themes involving circuses, fables, and animals and used them as their artistic inspiration. In addition, both were sons of artists (Picasso’s father was a mediocre painter, Calder’s was a famous sculptor) who cultivated “English dandy” looks and attire—so alien to their sons’ sturdy peasant physicality and their offspring’s love of the primitive and marginal.

Despite living in Paris at the same time, Picasso and Calder were not friends, but they conducted a sort of artistic dialogue for decades after their first meeting in 1931 and their famous encounter at the Spanish Pavilion during the Paris International Exposition in 1937 (when Picasso exhibited Guernica and Calder his mercury fountain). They both explored the same themes of line, volume, and space that lay at the foundation of abstract art. However, though they started by examining similar techniques and themes, they inevitably ended up in different places after decades of creating.

Pablo Picasso. Woman Seated in a Red Armchair/Femme assise dans un fauteuil rouge (1932). Musée national Picasso-Paris. © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Mattieu Rabeau, © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

In the 1930s, Picasso was at the height of his mastery (what John Richardson calls his “triumphant years”), as is so beautifully demonstrated by his Woman Seated in a Red Armchair. The 1932 painting evokes 16th-century Madonna paintings—featuring the same deep reds and a creamy oval of a halo or a traditional head-covering mantle—but then it leads the art of portraiture into the world of Picasso’s modernity, with facial features reduced to lines, those “comma-shaped” hands, and the figurative that is simplified all the way to abstract and surreal.

Alexander Calder. Hercules and Lion (1928). Calder Foundation New York. Photo: Installation view of “Calder-Picasso” at the de Young Museum, photography by Gary Sexton. © 2021 Calder Foundation New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

At the same time, Calder—a skilled metal worker, sculptor’s son, and an artist fascinated by the space between objects and the invisible that affects the visible—produced his “drawings in space” (a term coined in 1929 to describe his fanciful wire sculptures). At the de Young exhibition, there are several delightful examples of this period in Calder’s biography—the time when he moved from magazine illustrations and “flat” drawings to his preferred subject of conquering space, this time with wire. His acrobats, dancers, and animals are all wire-wrappings that can be simultaneously viewed as sculptures and as flat shadows, changing with each angle of viewing. The term “drawings in space” accurately describes these sculptures. . . when they are viewed in a photograph, but in real life, they are tridimensional structures. A limb is actually away from the body, a profile is actually a face delineated by height and width but also by depth, and the figures dance, move forward, or have a hulk and presence like the Hercules above. We understand the three dimensions (because that is how we perceive all objects), but Calder is trying to add a fourth one—time, or at least movement. While these sculptures merely suggest movement, while exploring empty space in between the lines marked by wire, Calder eventually ended up inventing mobiles that moved at all times—something that sculptures before him rarely did.

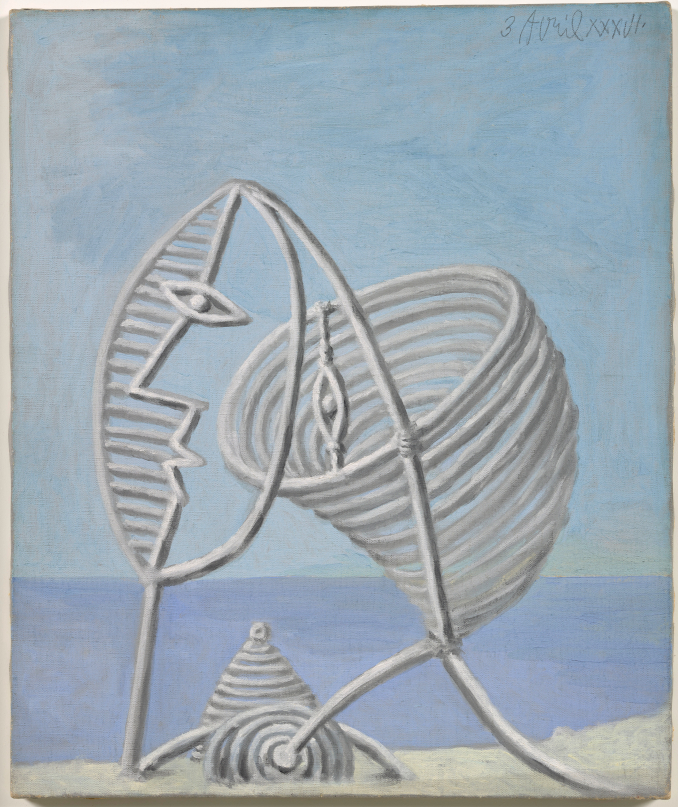

Pablo Picasso. Portrait of a Young Girl/Portrait de jeune fille (1936). Musée nationale Picasso-Paris, Pablo Picasso Acceptance in Lieu, 1979. © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Adrien Didierjean, © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

When Picasso played with metal wires, he either made small figurines, or he put the tridimensional lines into a flat painting (above) or even explored the ready-made, as in this wartime sculpture of a bull, created from bicycle parts. Like Calder, he was fascinated by lines, as well spaces between things and their unexpected juxtapositions, but his approach was more to deconstruct (that is, reduce), as opposed to Calder’s approach, which was to construct or assemble. But while Calder might add where Picasso would subtract, they both transformed abstract art beyond the simple lines and dots of Miró or Kandinsky.

Pablo Picasso. Bull’s Head/Tête de Taureau (1942). Photo: Fundacion Almine Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, Madrid. © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Photograph © FABA, Éric Baudouin Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Nothing is a better illustration of this thought process than this series that Picasso created in 1945. He started out with a bull image that bears a strong resemblance to those found in the Altamira caves in his native Spain—paintings by Paleolithic artists. Picasso, a master of any genre and any line, would then reduce and transform his bull image into an icon of a bull or even into a “concept of a bull” until he ended up with what we are now used to calling “a Picasso “—just a few perfect lines that give an idea of the animal, its horns and bulk, but with none of the realism of older art.

Pablo Picasso, The Bull series/Le Taureau (1945). Musée national Picasso-Paris. Photo: Installation view of “Calder-Picasso” at the de Young Museum. Photography by Gary Sexton. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

For Calder, it was not enough to explore the space between lines in his wire sculptures, no matter how delightful and popular they were. By the early 1930s, he was experimenting with spheres suspended on wires, and by the 1940s he was in full swing with his mobiles (a term famously coined by Marcel Duchamp): the structures we have come to associate with Calder art and which added one more element—movement—and made his creations unique. Whether this involved the gentle swaying of “leaves” on thin wires, or the whirling motion of heavier structures (for example, his works in the A Universe series of the 1940s and On One Knee in 1944), the realm of the invisible that so fascinated the artist was now explored through motion. In this unique way, Calder added one more dimension.

Alexander Calder. Scarlet Digitals (1945). Calder Foundation New York; Promised gift of Alexander S.C. Rower. © 2021 Calder Foundation New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Courtesy Calder Foundation New York/Art Resource, New York. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Calder, of course, did not stop with his mobiles, moving on to stabiles—sculptures of fused sheets of metal that eventually became the monumental works that adorn major public spaces, especially in North America.

Alexander Calder. La Grande Vitesse (1:5 intermediate maquette of the sculpture in Grand Rapids, Michigan) (1969). Sheet metal, bolts, and paint, Calder Foundation New York. © 2021 Calder Foundation New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Courtesy Calder Foundation New York/Art Resource, New York. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The two artists ceaselessly explored the possibilities of expression in abstract, or at least modern, art. Both were masters of lines and spatial deconstruction (or construction), and even if they were not personal friends, artistically their lives ran in interesting parallels.

The exhibition allows viewers to appreciate these delicious parallels by placing together their artworks from the same period or representing a similar theme.

Left to right: Alexander Calder, Helmet with Eyes (1946) and Pablo Picasso, Vanitas (1946). Installation view of “Calder-Picasso” at the de Young Museum, photography by Gary Sexton. © 2021 Calder Foundation New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Here is Picasso’s Vanitas—his variation on the popular 17th-century theme of vanitas—devotional still-lifes with skull intended to remind the viewer of life’s impermanence. Picasso’s painting is juxtaposed with Calder’s oil from the same year—you could call it a painting of a bronze sculpture, so much the artist’s eye is drawn to the idea of tridimensional space. Other inspiring parallels include mid-1950s paintings of the artists’ studios as well as their abstract sculptures from the 1960s. This is an exhibition that allows for art history discoveries and insights rather than just being an assemblage of significant works.

The Calder-Picasso exhibition is open until May 23, 2021 in San Francisco, to be followed by an opening in Atlanta, GA (June 26–Sept. 19).