Food for the Soul: Gustave Caillebotte – The Unappreciated Impressionist

Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, the Rainy Day (Rue de Paris, Temps du Pluie ), 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Impressionism owes a huge debt to Gustave Caillebotte but hardly anyone today knows his name.

By Nina Heyn- Your Culture Scout

Musée D’Orsay is one of the most visited places in Paris where millions of visitors admire Monet’s haystacks, Cézanne’s apples and Renoir’s pink-cheeked women. Very few of these visitors realize that an important part of d’Orsay’s collection has its source in a bequest of an equally talented but hardly recognized artist named Gustave Caillebotte.

For a long time, Caillebotte was mainly appreciated by his friends. They would collect his paintings, and he was their patron, buying their art, funding, marketing and organizing several of the Impressionist exhibitions. His friends happened to be called Renoir, Pissarro, Monet and Sisley.

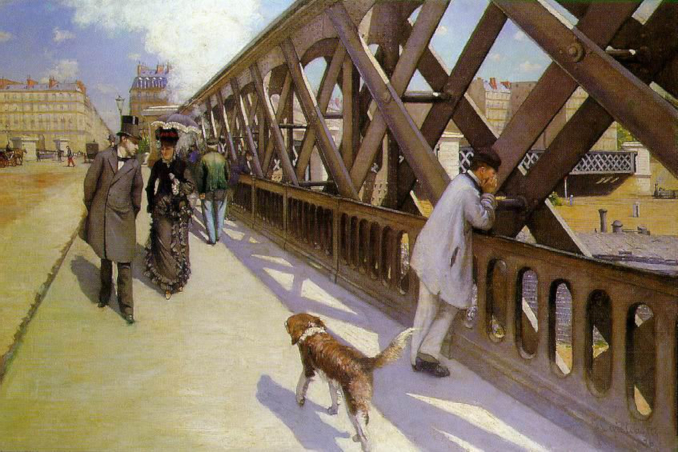

Gustave Caillebotte. Le Pont de L’Europe, c. 1876. Oil on canvas. Petit Palais, Geneva. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Caillebotte came from a wealthy family and, after obtaining his law degree, he could have entirely devoted himself to his favorite past-times of yacht racing and boat design (he was very good at both these things – winning races and getting yacht design awards). He could have also lived like most rich bourgeois in Paris – enjoying the fast-paced “modern life” that erupted in Paris after the Franco-Prussian war and the revolt of communards of 1871. It was the time of huge architectural changes in the city where narrow medieval lanes were razed down to make room for wide avenues. Spacious apartment blocks, clad in cream stone carvings, rose everywhere, and modern bridges with intricate ironwork railings connected both sides of the Seine. Between the early 1870’s and the Universal Exposition in 1889 that brought to Paris the Eiffel Tower, the City of Light was visually transformed into a world’s center of technological advances, where communication network consisted of new roads, telegraph lines and even the beginning of a telephone network. Ordinary city people started enjoying leisurely activities such as public dances (immortalized by Renoir in his Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette) and strolls across wide boulevards with vistas of the city.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (Bal du Moulin de la Galette), 1876. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. This painting was a part of the Caillebotte Collection donated to Musée d’Orsay

Caillebotte clearly enjoyed the city’s new look but instead of just participating in this life, he chose to enroll in the Fine Arts School (École des Beaux Arts), make acquaintance of all the artists he admired, and start painting. Although Émile Zola (France’s pre-eminent novelist who was a friend of Cézanne’s and a prolific journalist) criticized this new artist on the scene, a lot of his new friends recognized the emerging talent early on.

Gustave Caillebotte. Floor-Scrapers (Raboteurs de Parquet), 1875. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Caillebotte came to painting from an admiration of Manet, whose art is firmly rooted in classic and realistic canvases, and perhaps also from the artist’s own architectural eye. The first painting he submitted in 1875 to the Salon (the annual exhibition that could anoint a painter as an established artist or reduce his chances of success to nothing) was Floor-Scrapers – a realistic and very architectural image of men bent over the floor from which they are scraping grime. The lines of the floor planks, rectangular wall panels and an iron grille on the balcony create a feeling of a box – a cage really – in which these men are enclosed in their hard labor. The painting was promptly rejected by the Salon. Soon after Caillebotte bought his first Impressionist paintings, he got invited by Renoir to participate in the third Impressionist exhibition, and the Paris art scene gained a new modern artist. Caillebotte’s huge contribution to the new art was also in a form of his relentless and gracious patronage. He would buy a canvas from Renoir or Sisley to help out struggling artists, he’d pay Monet’s rent for years, and he’d discharge Renoir’s debts in his will. He would also fund and organize subsequent Impressionist exhibitions, as well as host his art friends at his country house. Renoir immortalized his friend in his masterpiece The Luncheon of the Boating Party where Caillebotte is the man sitting in the foreground, wearing a boater’s hat. This was painted at Gennevilliers, a summer retreat village not far from Paris, where Caillebotte had his summer house and where he ran his boat regattas.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Luncheon of the Boating Party (Le Déjeuner des Canotiers), 1880-81. Oil on canvas. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

An artist himself, Caillebotte recognized early on the immense cultural value and beauty of the new Impressionist art. In his will he bequeathed his collection to the French state on condition that it is kept together and displayed at the Louvre or the Luxembourg museum. The state promptly rejected this legacy, relenting a few years after Caillebotte’s death, accepting 27 out 67 canvases. There were 7 paintings by Degas, 8 Monets, 6 Renoirs, 7 Pisarros, 5 Sisleys, 2 Cézannes and…only 2 Caillebottes. In 1928 the collection eventually ended in the newly created Musée d’Orsay. It is thanks to Caillebotte’s taste and generosity that Renoir’s Dance at the Moulin de la Galette is now the star of this museum, and that the masterpieces of all major representatives of the movement are united in one French cultural institution. It is only sad that the architect of this collection did not have the same fate. His own legacy of several hundred artworks is dispersed all over the world. His most famous canvas, Paris Street, the Rainy Day is now the star of Art Institute of Chicago, his Pont de L’Europe is in Geneva, his Sunflowers Along the Seine are in San Francisco, and his charming daisies paintings can now be found at the Impressionist museum at Giverny.

Gustave Caillebotte. Yellow Roses in Vase (1882). Oil on canvas. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Degas was in conflict with Caillebotte (as well as with many other fellow painters) but it has not stopped him from collecting Caillebotte’s art and from purchasing one of the best paintings (Yellow Roses in Vase, now at Dallas Museum of Art) about a year after his enemy’s passing.

Ironically, one of the “flagship” images of Impressionist movement has been created by Caillebotte rather than by his more popular colleagues. Paris Street, the Rainy Day that seems to capture a fleeting moment in a city street is actually a complex composition, for which Caillebotte made numerous studies and architectural sketches. Even the rain-glistening cobblestones have been carefully planned and sketched. All this preparation does not take away from the mood of this paintings. Almost like in a film shot, we have action of various actors moving diagonally through a scene. The “set décor” is provided by angled view of the new Haussmann apartment blocks and the rain-slicked street.

Here is a photo of the same street corner in contemporary Paris:

Place de Dublin/ Rue de Moscou, Paris. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps Caillebotte’s artistic misfortune was that, as a rich heir, he was more of a gentleman-artist than a full-time painter. If he had to paint for a living all the time, perhaps there would have been a larger body of works for us to enjoy today. The other reason for him being a “less appreciated Impressionist” might be that his canvases, now that we look at them 150 years later, are really at crossroads of several styles.

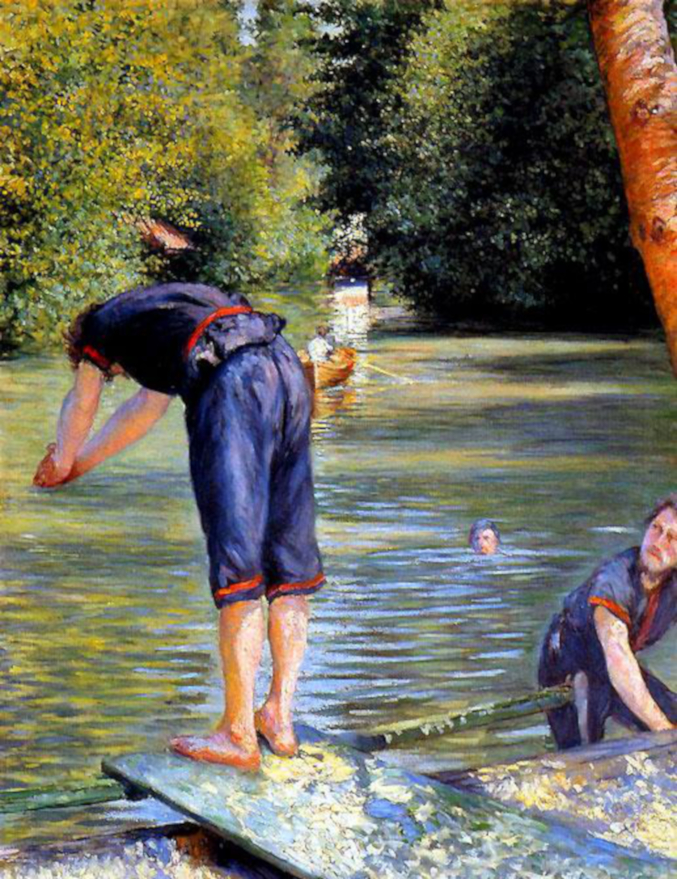

Gustave Caillebotte. Bathers (Baigneurs), 1878. Oil on Canvas. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Caillebotte’s compositions are complex and visually much more on the road towards modern art than the “classic” Impressionism. The Bathers has little of Impressionism in it. Other than some dapples of light on water, the tress in the background and people are quite realistic, and the image crop is what we would expect in a contemporary photo. His later paintings, like Landscape – a Study in Yellow and Rose (1884) are mainly flat planes of color – very much like the 20th century art that was just round the corner of art history. Since 1970’s Caillebotte’s stature in the world of art has been steadily growing but he is still one the most unappreciated of the Impressionist group he helped to create.