Food for the Soul: Rosa Bonheur – Women & Art Series 10

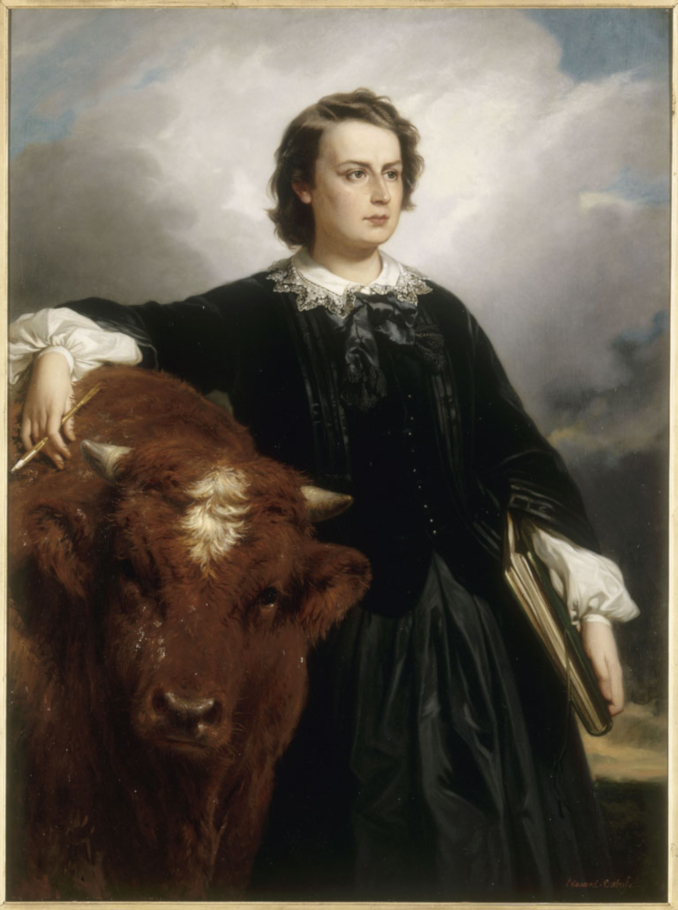

Edouard Louis Dubufe. Portrait of Rosa Bonheur (the bull was painted by Bonheur), 1857. Oil on canvas. Versailles Palace. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

There is a reason why the traditionally dressed Victorian lady in the portrait above is resting her hand on a bull instead of a chair or some other conventional prop. While the lady, Rosa Bonheur, was painted by the portraitist Édouard Louis Dubufe, Bonheur herself painted in the bull after deciding that a “boring chair” would not be appropriate for any description of her as an artist. And she could not have been more right.

Rosa Bonheur had an unconventional childhood, followed by an even less conventional life. Her father, a minor painter, taught her and her three younger brothers the craft. He was not just an artist but a freewheeling spirit, a man seduced by the egalitarian and feminist ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon; as such, he was not fazed by the fact that Rosa was a tomboy, who was thrown out of a girls’ school for unladylike behavior. He tutored his unruly but extremely talented daughter himself, sent her to the Louvre to copy masterpieces, and allowed her to keep a menagerie of animals at their Paris residence. This highly unconventional schooling paid off, for by the age of 19, Rosa’s first animal paintings were accepted to the Salon of 1841.

Rosa Bonheur. Ploughing in the Nivernais or The First Dressing, 1849. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Rosa did not paint what other Victorian-era ladies tended to paint—such as flowers and landscapes—and did not even paint portraits that much. She was only interested in animals. She would roam forests and visit farms, and then she started attending slaughterhouses and animal fairs to study animal anatomy.

Ploughing in the Nivernais, painted right after the 1848 Springtime of the Peoples (a wave of nationalistic uprisings and social revolts that swept through Europe and shook French society), was considered by critics a metaphor of the rebirth of the French nation; it also brought Bonheur acclaim as an outstanding realist painter of nature. While farm scenes were common in the 19th century’s realist canvases, they typically focused on the beauty of a landscape or perhaps the toil of peasants. Ploughing in the Nivernais, on the other hand, is all about the group of muscled oxen marching through an autumn field, cutting through the buttery earth and looking strong, almost majestic. Whereas their human overseers are anonymous, with their faces hidden by wide-brimmed hats, the animals are more individualized—each of the huge beasts with a different color, gait, and expression. Bonheur’s focus, both in composition and in technique, is on the animals. Interestingly, when London’s National Gallery did a restoration of their version of her famous canvas The Horse Fair, they discovered that while Bonheur used broad strokes for the sky and earth, she used minute strokes of a very fine brush to render the horses’ coats.

Rosa Bonheur. Haymaking in Auvergne/La Fenaison, 1855. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The success of Ploughing in the Nivernais was the beginning of Bonheur’s fame as the most accomplished animal painter in France. It marked a period of huge strides as an artist but also a period of personal happiness. A few years earlier, Rosa had encountered Nathalie Micas, a painting model of her father’s, with whom she formed an instantaneous and unbreakable bond (even Nathalie’s father blessed this bond on his deathbed a year later). Nathalie stayed at Bonheur’s side as her life partner, business manager, and artistic assistant until her death over 40 years later.

Rosa Bonheur. The Horse Fair, 1852-1855. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bonheur’s most famous painting is the enormous canvas titled The Horse Fair. She had prepared for this work for 18 months by attending, twice a week, a horse trading market in Paris. She even obtained a police permit to be able to dress in pants when sketching and observing at the market. That saved her the harassment of horse traders who would not have ignored a young woman in a crinoline and bonnet, but it was also probably a relief for the unconventional Bonheur to be able to move around freely. Later, pants became her trademark painting attire to the point that the French president insisted that she receive him wearing them so that he could see “how the artist worked.”

The massive 8 x 16 feet (244 x 506 cm) artwork depicts a scene at the Paris horse market (the dome of La Salpêtrière hospital is visible in the background). Exhibited in the Salon of 1853, the scene of bucking Percherons tossing their heads with flying manes and straining their enormous muscles excited the crowds of viewers and brought Bonheur to the heights of fame and recognition.

There are two versions of Horse Fair, but neither version of the artist’s most famous painting resides in her native country. The American one was purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt and then offered to the Met; the other, smaller one is at the National Gallery in London. Bonheur initially offered the painting to the city of Bordeaux, but the offer was rejected. Instead, her dealer Ernst Gambart purchased it and came up with a clever marketing campaign. He then sold the painting for the huge sum of 40,000 francs, but only after reserving the right to tour the painting for three years (including in England and the U.S.) and to strike engravings that made the canvas famous and the entrepreneur rich.

Rosa Bonheur. El Cid, 1879. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

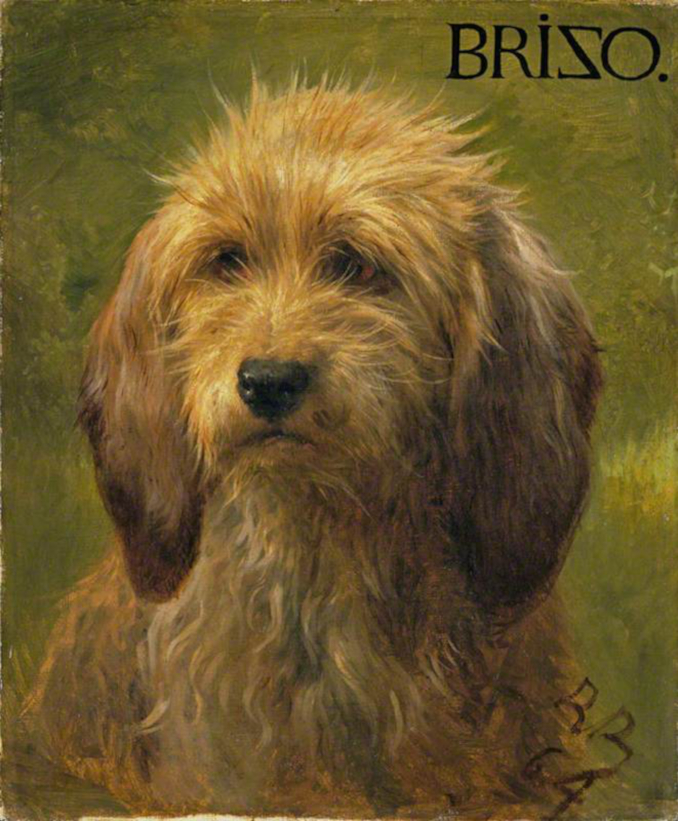

To Bonheur, animals were people—creatures with individualized expressions and great faces to be painted. One of the most famous animal portraits is at the Spanish Prado museum. This majestic head of a lion is named El Cid (implying both the name of a valiant Castilian knight and the term for a “lord” or even a “prince”). It was donated by Bonheur’s dealer to the museum. Bonheur always had a fondness for lions; in fact, she even kept a pair in her private zoo on her property of Château de By near Fontainebleau. Not all Bonheur portraits were of exotic creatures, however, as evidenced by the tender portrait below of a hound named Brizo.

Rosa Bonheur. Brizo the Shepherd’s Dog, 1864. Oil on canvas. The Wallace Collection, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bonheur was (excuse the pun) lionized by the public and royalty alike. French Empress Éugenie, after a spontaneous visit to Bonheur’s residence, returned there a year later and pinned on her a Légion d’Hônneur medal—with Bonheur becoming the first woman to be awarded this distinction in the arts. Queen Victoria requested and enjoyed a private viewing of The Horse Fair when the painting was touring Britain. Bonheur also received medals from the king of Spain and the hapless Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, as well as invitations to royal courts all over Europe. She also got rave reviews in America.

Photo of Rosa Bonheur, 1890s. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, none of her titled patrons nor art critics seem to have minded the fact that Bonheur openly lived in relations with women (first with Nathalie, and after the latter’s passing, with American artist Anna Klumpke), wore pants (even if permitted by police), kept her hair short, smoked cigars, and generally ignored all the rules of appropriate behavior for women in rigorous “polite society.” As Empress Éugenie declared, “genius has no gender.” Bonheur’s passion and admiration for the animals she portrayed seems to have swept away any social objections.

Rosa Bonheur. Portrait of Col. William F. Cody, 1899. Oil on canvas. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Even toward the end of her life, Bonheur lost neither her amazing skill at portraying animals nor her curiosity about the unconventional. Buffalo Bill enthralled Europeans with his Wild West exhibition when he took it to Paris for the Exposition Universelle in 1889. Bonheur visited the grounds of Cody’s Wild West attraction to sketch the exotic American animals and the Indian warriors with their families. Cody, in turn, accepted her invitation to visit her château in Fontainebleau, where she painted his portrait. For Bonheur, the colorful character of Col. Cody seems to have embodied the freedom and independence of the United States, a young country so different from codified and formal France. In this painting, however, she shows Col. Cody as a somewhat distant figure gazing away, while his white steed faces front and is painted with minute detailed attention to his spots and fine hair. Again, it is the horse that is the ultimate star of the painting.

Rosa Bonheur. The Highland Raid, 1860. Oil on canvas. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. National Museum of Women in the Arts. Washington. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It is ironic that one of the most popular painters of the 19th century eventually became one of the most unfashionable ones. Even within the realistic style, Bonheur’s genre of animal pictures eventually was overshadowed by academic art of historical scenes and the landscapes of the Barbizon school. By the 1870s, Impressionism had begun challenging realistic paintings, and by the time Bonheur passed away in 1899, art, especially in France, had moved in a myriad of different directions, none of which included her kind of painting. Even Bonheur’s Château de By fell into disrepair after the death of her last companion Anna Klumpke in the 1940s. Only very recently did a French businesswoman and her daughters purchase the property; they are in the process of restoring it and bringing back Bonheur’s memory. This will perhaps help to move Bonheur from being just a poster child for early emancipation to an artist recognized for her unique, emotional paintings.