Food for the Soul: Magdalena Abakanowicz – Women & Art Series 11

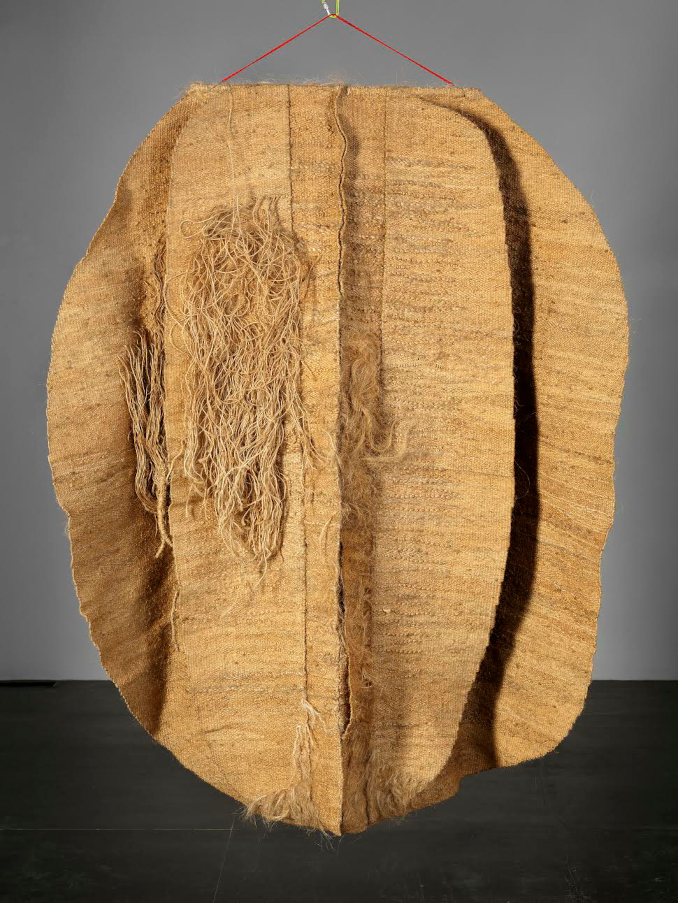

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Abakan Orange, 1971. Sisal. Jankilevitsch Collection. Photo: Marcin Koniak/Desa Unicum, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“Art does not solve problems but makes us aware of their existence. It opens our eyes to see and our brain to imagine.” ~ Magdalena Abakanowicz

In 1962, a young woman submitted her abstract Composition of White Forms, woven of earth-colored cotton yards, for a competition at the first Tapestry Biennal in Lausanne. This competition entry launched the career of a unique mixed-media artist, and it helped to change the status of textile works from “craft” to “textile art.” That artist was Magdalena Abakanowicz, a fiery young noblewoman from eastern Poland (with ancestry tracing all the way back to a certain Genghis Khan) who liked to use wool yarn, sisal rope, and other industrial fibers in a way that Western artists—raised in the long tradition of tapestry as a flat wall covering that mimics a painting—could not even approach. Her monumental fiber surfaces (kilims? tapestries? gobelins?) were like nothing ever created before.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. La Robe Blanche / Abakan Lady, 1972-1975. Sisal. ©Marta Magdalena Abakanowicz Kosmowska and Jan Kosmowski Foundation. Photo: Marek Gardulski/Galeria Starmach, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

The traditional tapestry industry, mostly Belgian and French, was at the time dominated by male artists, who created designs but did not make them—the actual works were executed by manufactories and weavers. With her submission to the Lausanne competition, Abakanowicz went against all of these conventions—a woman designer from eastern Europe whose submission was a huge, almost 20-ft-long vertical abstract composition that she also made by hand herself. Her tapestry won a medal, but the artist herself never attended the event since she lived behind the Iron Curtain in Poland. Traveling abroad required money and a state permit to travel—she had neither. The same thing happened a few years later when her textile composition won a gold medal in Sao Paolo; the artist, again short of money and a travel permit, did not attend. Soon after the Lausanne show, however, grants and show invitations enabled Abakanowicz to travel to the West and establish herself as one of the most inspiring contemporary artists. Since the late 1960s, her fame has spread all over the art world, catapulted by her clear transcendence beyond traditional textile art and entry into the world of sculpture and abstract art.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Turquoise Abakan, 1969. Flax, sisal, textiles. National Museum in Warsaw, inv. no. SZW 745 MNW. Photo: Teresa Żółtowska-Huszcza, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

Abakanowicz’s wool and jute compositions, looking like a cross between multidimensional kilims (Turkish rugs or carpets) and textured exotic plants, were featured in a 1969 documentary film titled Abakans by Jarosław Brzozowski and Kazimierz Mucha. Because her large, fibrous structures did not fit into any existing genre, the filmmakers simply created one from her family name. The name stuck and “Abakans” became a perfect, unique moniker for her art.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Abakan Yellow, 1967. Sisal, mixed media. National Museum in Poznań, inv. no. MNP Rw 1839. Photo: Sławomir Obst, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

In 1965, Abakanowicz started to teach tapestry and textile art at the State Graduate School of Art at Poznań University. Even though she acquired a devoted following of students who flocked to her classes from all over the world, she resisted having her creations categorized as textiles or even anything one-dimensional. Moving beyond the two-dimensional Abakans textile hangings—some of which were exhibited at New York’s MoMA and in Chicago in the early 1970s—she started exploring tridimensional, “winged” structures and grew more and more interested in sculpture, or at least in the architectural aspects of fibrous art.

Magdalena Abakanowicz at State School of Decorative Arts at Poznań University, mid-1960s. Photo: Jerzy Nowakowski, Collection of Poznań Art University, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

Abakanowicz’s artistic transition is well documented and honored by a current exhibition at the Artistic University of Poznań. That art school has just been named after Abakanowicz (who spent 25 years teaching there), and to celebrate this event, the National Museum in Poznań has mounted an outstanding show of some of her most famous and seminal works. The exhibition’s title is a quote from the artist: “We are fibrous structures.” Her early Abakans are definitely that—fibers that evoke the viscosity and texture of human tissues:

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Black Abakan (detail from 2021 exhibition at the National Museum Poznań). Photo: Malgorzata Kossut

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Turquoise Abakan (detail from the 2021 exhibition at the National Museum Poznań). Photo: Malgorzata Kossut

The fascinating exhibition showcases not only the famous Abakans (a major feat since the museum had to assemble these huge, complicated works from faraway museums and private collections during pandemic restrictions) but also the next steps in the artist’s development. She once declared: “My weaving and use of soft materials comes out of my need to protest. A desire to question all the rules and habits connected with the material.”

In the 1970s, Abakanowicz moved on to abstract structures, like those made out of burlap sacks and sailing ropes:

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Embryology, 1978. Burlap, cotton gauze, hemp cord, sisal, nylon, 51 pieces, variable dimensions. Starmach Gallery, Kraków. Photo: Marek Gardulski/Starmach Gallery, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

And then, almost inevitably, she started to explore human figures.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Untitled, 1990–2000. Burlap, resin, 30 objects. ©Marta Magdalena Abakanowicz Kosmowska and Jan Kosmowski Foundation. Photo: Marcin Jagiellicz/All That Art! Contemporary Art Foundation, Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

Abakanowicz made her name living in the materially limited world of communist Poland—where even the simplest art materials were hard to obtain, foreign travel was limited, and art was sometimes criticized for suspect political content. Her early works were made from the simplest materials (laundry clotheslines, sizal cords, yacht ropes, burlap grain sacs, even some branches found by the roadside). At the same time, the artist struggled against having her work categorized as “decorative art” (as tapestries ordinarily would be); though she was using craft fibers, an affordable and plentiful material, clearly she did so as a means toward the expression of pure art.

Through her Abakans and then numerous figurative installations, Abakanowicz explored her ideas about what moves or inspires or animates a human body. The relationship of the flesh to consciousness—probed so insightfully in a Zen koan (Hsu Yun’s famous “Who is dragging this corpse around?”)—seems to be a central tenet of Abakanowicz’s later art. She created entire tribes of barely human figures, often headless or misshapen—human and dehumanized at the same time—not unlike the contemporary world that we all live in.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Fox, 2009. Burlap, resin, iron. Marta Magdalena Abakanowicz Kosmowska and Jan Kosmowski Foundation. Photo: Wojciech Holnicki-Szulc. Courtesy of National Museum Poznań

Moving into figurative art relieved Abakanowicz of the unwelcome label of craft or textile maker and allowed her to use the unconventional medium of fiber to create her disturbing, truncated figures—hunched, headless, anonymous, but powerfully present. Her installations moved outside to park and museum settings. She started creating groups of figures and eventually, like so many sculptors, ended up creating some of them in the most venerated of sculpture mediums—the bronze.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Unrecognized/Nierozpoznani installation. Poznań Cytadela Park. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Abakanowicz passed away in 2017, leaving behind an art landscape populated with works made out of any material imaginable by scores of artists who went on to further blur the lines between craft, installation, sculpture, painting, and other mediums of expression. These days, museum-goers routinely encounter objects admired as art that owe something to the pioneering eye of this woman from a remote corner of Europe. Once you have seen an Abakan or her installation of headless hunched human shapes, all subsequent forays in contemporary art gain a bit more context—you can see where they may have come from, and sometimes they definitely come from the unique world of Magdalena Abakanowicz.

The exhibition “We Are Fibrous Structures” is open at the National Museum in Poznań, Poland from Aug. 8 through Oct. 24, 2021.