Food for the Soul – Georgia O’Keeffe: Women & Art Series 12

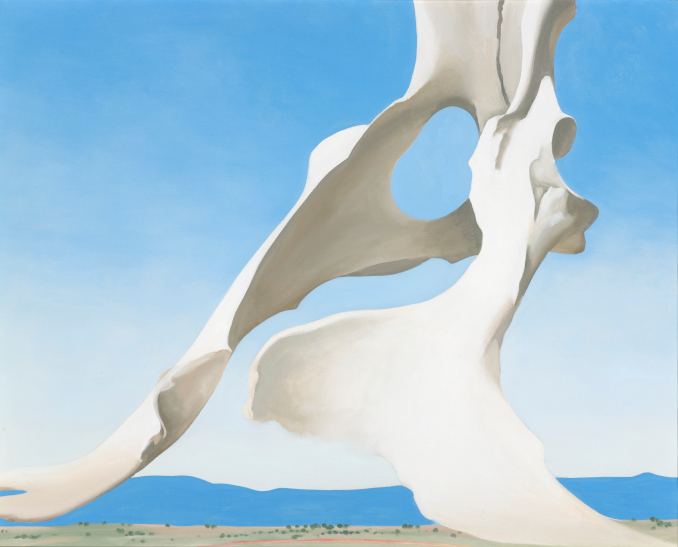

Georgia O’Keeffe. Pelvis with the distance, 1943. Oil on canvas. Indianapolis Museum of Art, Newfields, IN. © Indianapolis Museum of Art/Gift of Anne Marmon Greenleaf in memory of Caroline M. Fesler. Photo: Bridgeman Images © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

“I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.” ~ Georgia O’Keeffe

Photo of Georgia O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz (1918). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, donated by MET to Wiki. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Georgia O’Keeffe painted flowers for a dozen years in the 1920s and early 1930s. Before that, she painted abstract watercolors, New York skyscrapers, and views of Lake George in upstate New York. After her flower period, she painted the black and red hills of New Mexico, sun-bleached cattle skulls, and the sunset skies of the western United States. But the public will always associate her with those enormous lilacs, irises, and calla lilies.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Oriental Poppies, 1927. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Museum Purchase (1937.1). Photo: Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

Unlike most artists, O’Keeffe did not really have much of a struggling artist phase. Already in 1910, the 20-something Georgia was part of the modernist movement in American art, and by 1920 she was a celebrity artist. Her 1916 meeting with New York gallerist and photographer Alfred Stieglitz changed her life and helped to place her in the center of the city’s art scene. He accepted her early works for a show in his prestigious gallery (where he exhibited Braque, Matisse, and other masters of modernism), and soon she became his muse (he took over 300 portrait photographs of her), his principal gallery artist, his lover, and eventually his wife in 1924. They stayed together until his death in 1946, living the life of celebrated bicoastal artists (winters in New York, summers first at Lake George and then in New Mexico) working at the forefront of American art.

None of these biographical facts explains O’Keeffe’s artistic path, however—the road she took was unique and very much her own. While she was attracted to Art Deco and the abstract styles of her era, O’Keeffe’s paintings of New York buildings or her views of the serene Adirondack hills were from her point of view. She showed city towers at sharp and sometimes menacing angles, enveloped in halos of sun or artificial light. Her lake views were also very far from being stereotypically “feminine” depictions of nature—instead, she painted black blocks of barn houses and dark swaths of stormy sky. Even her partner and champion Stieglitz was reluctant to exhibit her more “masculine” works, favoring the ever popular flowers.

Georgia O’Keeffe. The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y., 1926. Oil on canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago. IL© Art Institute of Chicago/Gift of Leigh B. Block/Bridgeman Images © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

For an American museumgoer, O’Keeffe is a very familiar artist. Her works can be found in many American art institutions; they grace book illustrations and souvenir merchandise, and her biography is taught at schools. In Europe, her artworks are much less common because few of her works are in permanent collections. The ongoing exhibition at Centre Pompidou in Paris is literally the first-ever major solo exhibition of this artist in France. The Modern Art Museum at Centre Pompidou has put together an exhibition that aims to present O‘Keeffe not only as a celebrated woman artist and representative of American modernism but also to show the full scope of her work, far beyond the famous flowers.

Installation view of “Georgia O’Keeffe” exhibition in 2021 in Paris, National Modern Art Museum, Centre Pompidou. Photo: Audrey Laurans for Centre Pompidou, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

Not that there are no flowers in the Paris exhibition. Some of O’Keeffe’s most beloved flower compositions have made it to Paris from a dozen American museums, illustrating so well the visual shock that is still unleashed on viewers when confronted with these enormous chalices of plants that become a Rorschach test of the viewer’s imagination.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Series I White and Blue Flower Shapes, 1919. Oil on board. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, courtesy Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Photography: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

O’Keeffe’s early art, roughly in the period between the two world wars, was at the crossroads of many intellectual and artistic influences. Modern art had been liberated by abstractionists like Wassily Kandinsky and expressionists like August Macke from the burden of a faithful representation of objects. There were also many styles ongoing at the same time—from surrealism to fauvism, from cubism to futurism, from Art Deco to the sinuous Art Nouveau artwork still popular in advertising. For O’Keeffe to paint her hyperrealist flowers in the 1920s—or in 1924, a sunset that is almost an abstraction in Red, Yellow and Black Streak—was proof of her untamed individualism and genuine artistic originality. These days, she is often celebrated as a feminist or at least as a “woman artist.” The Pompidou show is more expansive, presenting her art as work created by an exceptionally individual and mature painter who never stopped searching for unique points of view.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Red, Yellow and Black Streak (1924). Displayed at Centre Pompidou, National Museum of Modern Art, Paris. Gift of Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1995. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM- CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP© Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI.

Living on the 30th floor of a Manhattan tower, O’Keeffe naturally turned her gaze on New York’s skyscrapers, while her summers at the Stieglitz family property in Lake George resulted in her landscapes with black barns and lush green corn stalks. But these were “not her places,” as she once confessed. She found her “own place“ in 1929 when she visited an artist colony in Taos, New Mexico. The arid landscapes, the empty rolling hills, Kiowa tribe dances at night, and long walks in a red desert became the environment that nurtured this artist more than the lush but tame vegetation of upstate New York ever could have.

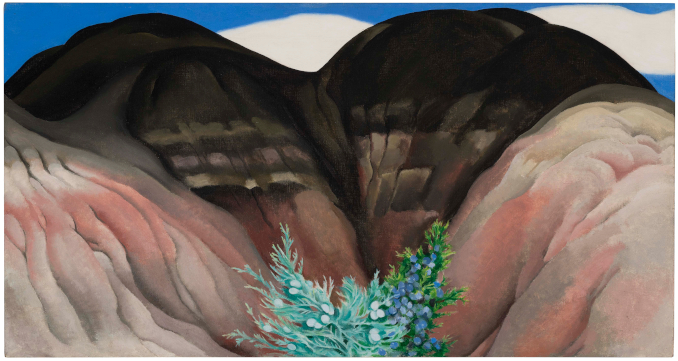

Georgia O’Keeffe. Black Hills with Cedar, 1941-1942. Oil on canvas. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. The Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest, 1981 (86.3471). Photo © Cathy Carver. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

For the next five decades (she passed away in 1986), O’Keeffe never tired of the arid and severe landscapes of the American West. Living in a succession of remote adobe houses, she contended with lack of plumbing, stifling heat, solitude, and rattlesnakes—a Wild West environment that likely would have overpowered many an explorer but that stimulated this woman with a pioneer spirit to create more and more sophisticated art.

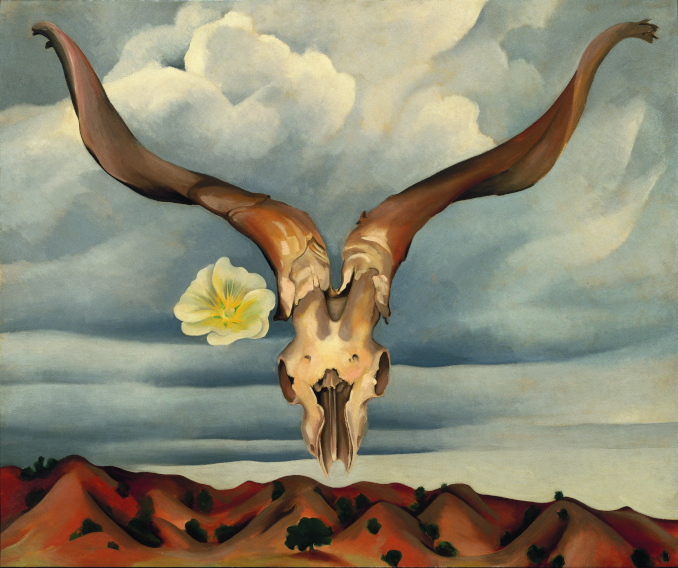

While the second World War raged in the world at large, O’Keeffe’s austere world of New Mexican deserts inspired her to create a series of paintings depicting animal skulls and bones against the bluest sky of the West. Part meditation on the transitory nature of life and part images of hope (she did, after all, paint the piercingly blue sky beyond), these were bold, modern images that preceded the hyperrealist art movement by decades.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills/Ram’s Head and White Hollyhock, New Mexico (1935). Brooklyn Museum. Bequest of Edith and Milton Lowenthal (1992.11.28). Photo: Brooklyn Museum © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Adagp, Paris, 2021, courtesy of Centre Pompidou

Where some would see lack of water and a hostile, uninhabitable desert, O’Keeffe perceived the grandeur of nature, the softness of the earth, and the stubbornness of desert plants that manage to thrive in a harsh climate. Those empty reddish hills inspired her to create some of her most striking landscapes—images that have remained fresh, modern, and beautiful decades after so many other art styles rolled through the 20th-century art scene.

For a painter, the advantage of living a long life is that there is time for evolution of style and reaching maturity. Who knows what we might have seen develop in the art of Masaccio, Raphael, Frédéric Bazille, or Aubrey Beardsley had they lived on instead of succumbing early? In O’Keeffe’s case, she had time to move beyond the landscapes (and far past her flowers) to the simplicity and elegance of “almost” abstract art.

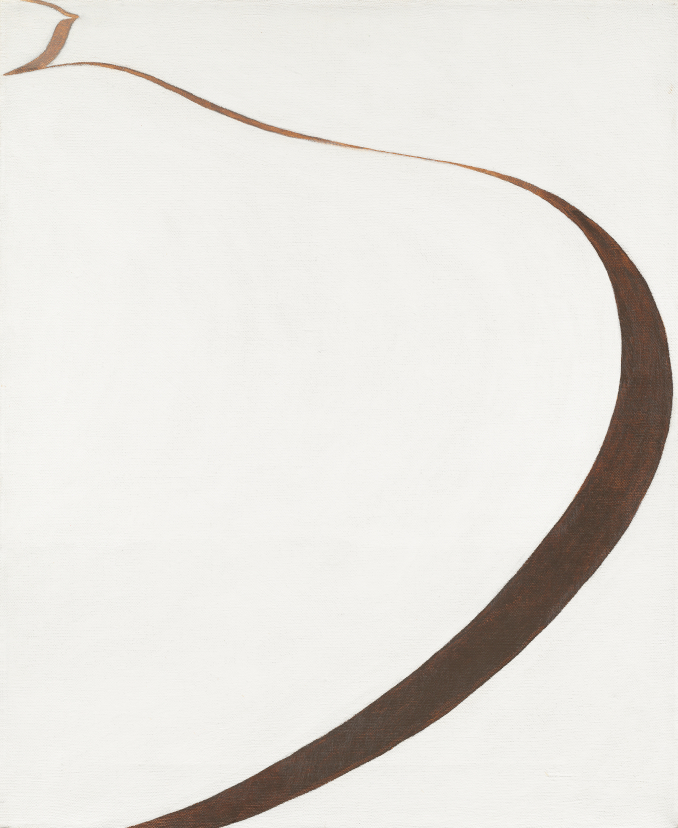

Georgia O’Keeffe. Winter Road I, 1963. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (1995.4.1). © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: courtesy of Centre Pompidou

Her Winter Road, painted in 1963, is such a picture. It looks like an abstraction—or perhaps some Japanese calligraphy—but it really isn’t. It is the artist’s way of reducing the landscape to its core element of a winding road. But it is also still a landscape where the emptiness of white canvas can be easily filled with our knowledge of all the hilly roads we have met.

The exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe runs from September 8 to December 6, 2021 at Centre Pompidou in Paris.