Food for the Soul: “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art” exhibition in Paris

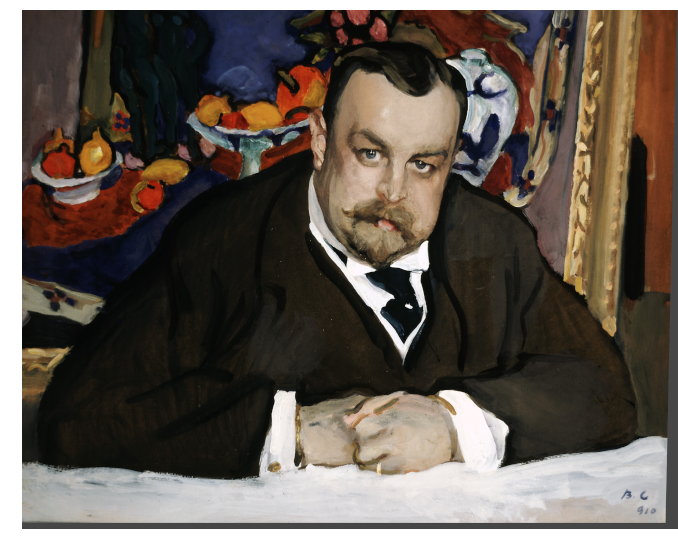

Valentin Serov. Portrait of the Collector of Modern Russian and French Paintings, Ivan Abramovich Morozov (1910). The State Tretiakov National Gallery, Moscow. © Tretiakov National Gallery, Moscow

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Paris is still the art center of the world. This notion was reinforced this year by a unique and massive exhibition currently mounted by Fondation Vuitton (a vibrant modern art museum in its own right) that provides a unique chance to learn about the history of modern art. “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art” exhibition reunites the finest Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings collected by the Morozov brothers at the turn of the 20th century, following these artworks’ dispersal among Russian museums for almost a century.

Paul Gauguin. Where Are You Going? – A Woman with a Fruit – Eu haere ia oe/Où vas-tu ? – La femme au Fruit (1893). Collection Ivan Morozov. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Photo: © State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, 2021

In the late 1800s, Michaïl and Ivan Morozov received an extensive art and humanities education as heirs to one of the grandest dynasties of textile manufacturers in Moscow. Their grand bourgeoisie family provided patronage to Russian Impressionists who in turn educated the brothers about art when the boys were teenagers. When, barely in their early twenties, the Morozovs decided to collect, the two rich, sophisticated, extensively traveled, and well-connected in the art world enthusiasts were perfectly positioned to take Paris by storm. The older one, Michaïl, amassed a collection of about 100 canvases of the best 19th-century paintings that included Renoir’s full-length Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary and Edouard Manet’s The Cork as well as works by Corot, Monet, Manet, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Michaïl was also the man who brought the first-ever paintings of Gauguin and van Gogh to Russia. His brother Ivan, who took up art collecting in earnest after Michaïl’s early death in 1903, is not only credited with bringing the first Picasso to Russia but also with spurring local artists to explore new artistic directions from Cubism to Fauvism.

Vincent van Gogh. Seascape at Saintes-Maries de la Mer /La Mer aux Saintes-Maries de la Mer (1888). Collection Michaïl Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Out of about 600 artworks that were originally in the collections of the brothers Morozov, about one third have traveled to the unique Paris exhibition, drawing from the Pushkin, Tretyakov, and L’Hermitage Museums in Russia—the three main depositories to which the collections were dispersed.

André Derain. Drying of Sails (1905). Collection Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2021

As a result of the 1917 Russian Revolution, the country’s capital was moved from Petrograd (soon to be named Leningrad and today called St. Petersburg) to Moscow. The newly nationalized collections of the Morozov brothers and that of their friend and art mentor, the industrialist Sergei Shchukin, were originally housed in the mansions of their owners. Eventually, a huge catfight erupted between L’Hermitage Museum and Moscow art institutions over which museum would be allowed to retain which of the paintings from both the Morozov and Shchukin collections. At the time, paintings were being sorted into those representing “worker and peasant subject matter” (alas, not many) and those deemed actively “reactionary, dimming class consciousness.” Others sought to allocate all old masters to L’Hermitage and all Russian art to the Tretyakov Gallery, but politics intervened again, especially after the State Museum of Western Art was dismantled in 1948. To make a long story short, not only was the collection of the Morozov brothers dispersed, but some thematic groups, patiently assembled by the younger Morozov, were broken up.

Ivan Morozov was a cerebral collector who would plan his acquisitions and wait for the right artwork to come to the market. In 1904, he bought Renoir’s Portrait of Actress Jeanne Samary, a picture that portrayed Samary in a similar way to a full-length painting of her that Ivan’s brother had purchased a few years earlier. The artist painted this beautiful and “classical Renoir style” painting in 1877. His famed pinks and fluttering brushstrokes are here at their finest.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Portrait of Jeanne Samary/Portrait de Jeanne Samary/ La Revêrie (1877). Collection Michaïl Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Three years later, in 1880, Renoir painted another half-length portrait, A Girl with a Fan/La Femme à l’Éventail, which featured Alphonsine Fournaise, one of his models from his masterpiece The Luncheon of the Boating Party.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. A Girl with a Fan/La Femme à l’Éventail (1880). Collection Ivan Morozov. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ivan Morozov found this portrait in 1908—five years after buying the first. When he hung them next to each other in his Moscow mansion, he would probably have experienced the same comparison that you can see here—noticing how much Renoir’s style had changed within three years (he moved toward a more classicizing style after 1880). The fascinating thing is that you can spot this at the Paris exhibition because the two canvases are expressly presented next to each other. However, after Morozov’s collection was confiscated and dispersed in the aftermath of the revolution and later during an especially virulent Stalinist period of the late 1940s, the two paintings got separated. Jeanne Samary’s portrait is now in Moscow while the Girl with a Fan is in St. Petersburg. The exhibition reunites them for the first time in a hundred years.

The exhibition is full of such thoughtful arrangements into historical or thematic groupings. This is particularly evident in the “Cézanne Rooms.”

Paul Cézanne. The Big Pine/Le Grand Pin (1895-1897). Collection Ivan Morozov. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Photo: © State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, 2021

Like Giotto and Picassso, Cézanne is a painter whose influence propelled Western art into a different direction. There is art before Cézanne, and there is art after Cézanne. The exhibition rooms called “Cézanne and cézannists” present Morozov’s finds of the best of Cézanne’s work, together with some Russian art that was inspired by this collection. Morozov discovered Cézanne in 1907 after seeing a posthumous homage show at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. In 1914, the Louvre finally accepted its first Cézanne painting, but only because it was a bequest (by the famous collector Isaac de Camondo). The French public was not entirely ready for this master—and yet by the same year, Morozov had already amassed a collection of 18 representative Cézanne paintings.

Paul Cézanne. Still Life with a Curtain/Nature Morte à la Draperie (c. 1892-1894). Collection Ivan Morozov. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Photo: © State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, 2021

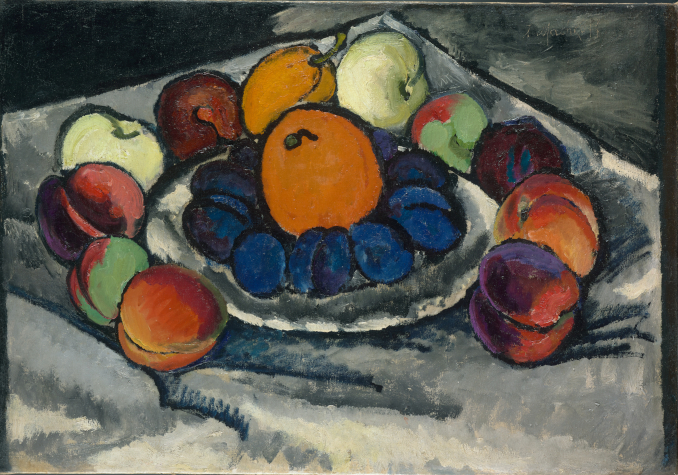

After Ivan Morozov’s haul of Cézanne art started arriving in Moscow—and especially two portraits acquired by Morozov in 1909 (Self-Portrait in a Casquette and Smoker)—the works influenced and inspired a whole generation of Russian artists to create in the new, “modern” style. The Paris exhibition displays paintings of Russian “cézannists,” especially Pyotr Konchalovsky and Ilya Machkov, next to Cézanne’s works, clearly showing how their art had profited from viewing Morozov’s collection.

Ilia Mashkov. Still Life, Plate of Fruit (1910). Collection Ivan Morozov. Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow. © Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow

Here is another example of how Western and Russian art connected through the Morozovs. After Ivan Morozov started acquiring Picasso’s and Cezanne’s portraits and bringing them to Moscow, many Russian artists who were part of this collector’s circle derived inspiration from these works in their own search for modern expression.

Pablo Picasso. Portrait of Ambrose Vollard (1910). Collection Michaïl Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Picasso’s tour de force portrait of his dealer Ambrose Vollard, which he painted to prove that you can express someone’s look and inner nature through a series of geometric shapes, inspired many painters in Russia. For example, Kazimir Malevich—who ended up with pure abstraction—reached out for deconstruction and a Cubist organization of space and color to create the Portrait of Mikhaïl Matyushin below.

Kazimir Malevich. Portrait of Mikhaïl Matyushin (1913-1914). Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow. © Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow

Unlike Sergei Shchukin—the pioneer of painting collectors of the era—the Morozov brothers did not collect exclusively Western art. In fact, they ended up purchasing twice as many contemporary Russian artworks as Western ones. In 1920, Ivan Morozov summed up his collection in an interview, saying that he left behind 430 artworks by Russian artists and 240 Western ones. Not only did he support known Russian Impressionists like Konstantin Korovin and Piotr Konchalowski, but he was, for example, the first collector of the Armenian Martiros Sarian in Russia.

Martiros Sarian. Street in Constantinople (1910). Collection Ivan Morozov. Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow. © Tretyakov National Gallery, Moscow

And then we come to Matisse….

Henri Matisse. The Moroccan Triptych. Installation view of the exhibition “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art.” Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

After Ivan Morozov acquired his first Matisse painting, called Bouquet/ La Vase aux Deux Anses in 1907 (at a time when “Matisse” was hardly a household name in France), he was introduced to the artist himself. Inevitably, this new acquaintanceship led the collector to further purchases. Morozov discovered Matisse precisely at the point when the artist’s style was undergoing a transformation from a darker palette and still lifes inspired by those of old Dutch masters and Simon Chardin into the vibrant colorful explosions that became his trademark. Morozov acquired older still lifes, like The Bottle of Schiedam (1896), while also commissioning new art featuring Matisse’s fully mature style. His patronage gave fruit to Moroccan Triptych that Matisse painted specifically for Morozov in Tangier. The order in which the three paintings were to be hung was specified by the artist, and it is even believed that he intended them to viewed from right to left (like Arabic writing), in order to experience the morning, noon, and evening light shown in the three scenes.

Henri Matisse. Moroccan Triptych, Entrance to the Kasbah/Triptyque marocain, La Porte de Casbah, right panel (1912–1913). Collection Ivan Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The one above is the city viewed through the door with the morning light.

Henri Matisse. Moroccan Triptych, Zorah on the Terrace/Triptyque marocain, Zorah sur la Terrasse, central panel (1912–1913). Collection Ivan Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Noon is represented by a portrait of Matisse’s model in Tangier, a girl called Zorah. The painting shows an interior in a blinding midday light. The Triptych goes from high contrast in the morning, to shimmering and ethereal in the midday, to Prussian blue shadows against apricot-colored earth in the last painting.

Henri Matisse. Moroccan Triptych, View from Window/Triptyque marocain, La Vue de la Fenêtre, left panel (1912–1913). Collection Ivan Morozov. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The three images are unified by their vivid shade of blue-green hue that varies with the light source and viewpoint. If a viewer fails to discern all this from labels and the catalog, Fondation Vuitton offers a delightful aid in understanding the exhibits in the form of “roaming docents.” The museum has about 30 curators who are available to explain the meaning of specific paintings or the logic of their arrangement. These “art guides” are multilingual, top-notch art historians who attract an enthusiastic following of visitors. Their help goes far beyond a standard museum audio guide—these are live experts ready to answer questions or draw your attention to connections and the meanings of what you are looking at. I have not encountered this level of “customer service” at any exhibition or museum anywhere.

Paul Gauguin. Te Tiare Farani/Flowers of France (1891). Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The beauty of this exhibition stems from the fact that it was put together by many art experts (on the French side led by curator Anne Baldassari, who previously was a director of the Parisian Museum Picasso); as such, it provides both an esthetic and educational experience. You can learn about life in pre-revolutionary Russia, about the artistic evolution of art giants like Matisse or Renoir, or about the art of collecting. Last but not least, you can see some of the greatest works of modern art that ordinarily are difficult for Western art lovers to access. Ivan Morozov collected exquisite Sisleys, hired Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis to create decorative panels for his mansion, and bought landscapes by Pisarro and Monet, as well as canvases by van Gogh, Vlaminck, Derain, Valtat, Vouillard, and Gauguin. His impeccable taste and deep pockets produced an epic collection in the history of art. Unfortunately, he did not get to enjoy it for long.

Edvard Munch. White Night/Girls on the Bridge (1903). Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Ivan Morozov could not cope with the advent of the Soviet Union. He did not have the foresight of Shchukin to move out of the way of the runaway train of revolution and failed to emigrate or remove his wealth in time. A few months after the revolution, in April 1918, Morozov had an encounter with the artist Sergei Konenkov, whose sculptures he had formerly bought, supporting Konenkov as Morozov did so many other young Russian intellectuals. This one proved to be ungrateful. An aggressive Konenkov showed up this time not as an artist but as a Bolshevik official with a preservation order, which meant the collection could not be destroyed by anarchists but was confiscated by the state. The naïve Morozov thought that this also meant that a local military unit would move out of his mansion, but the opposite happened. In 1919, Morozov was not only made a tour guide of his own private collection but was also told to vacate the premises immediately. This last humiliation was the final straw. He finally understood that there was no room for him in the worker’s paradise. Morozov used whatever was left of his money and connections to escape through the Finnish border with his wife and their little daughter, but the ordeal broke him. He lingered for a couple of years as one of hundreds of Russian emigrés in Paris and Switzerland. In May 1921, he went to a spa in Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in Czechia) to take care of his ailing heart. He died there on July 22, 1921.

Unknown. Museum of Modern Western Art, Cézanne Room, with paintings from the Morozov and Shchukin collections dominated by Blue Landscape (c. 1904-1906) of Paul Cézanne, former mansion of Ivan Morozov, 21 Prechistenka Street, Moscow, c. 1931-1932, gelatin silver print. Photo: Pushkin Museum archives, Moscow. Courtesy Fondation Vuitton

The exhibition “The Morozov Collection: Icons of Modern Art” runs in Paris between September 22, 2021 and February 22, 2022.