Food for the Soul: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney – Women & Art Series 13

Robert Henri. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 1916. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

In a press release issued in 1930, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney announced that she was launching a museum of American art because “…not only can the visiting foreigner find no adequate presentation of the growth and development of the fine arts in America under a single roof; the same difficulty faces the native who wants to get what American art is all about.”

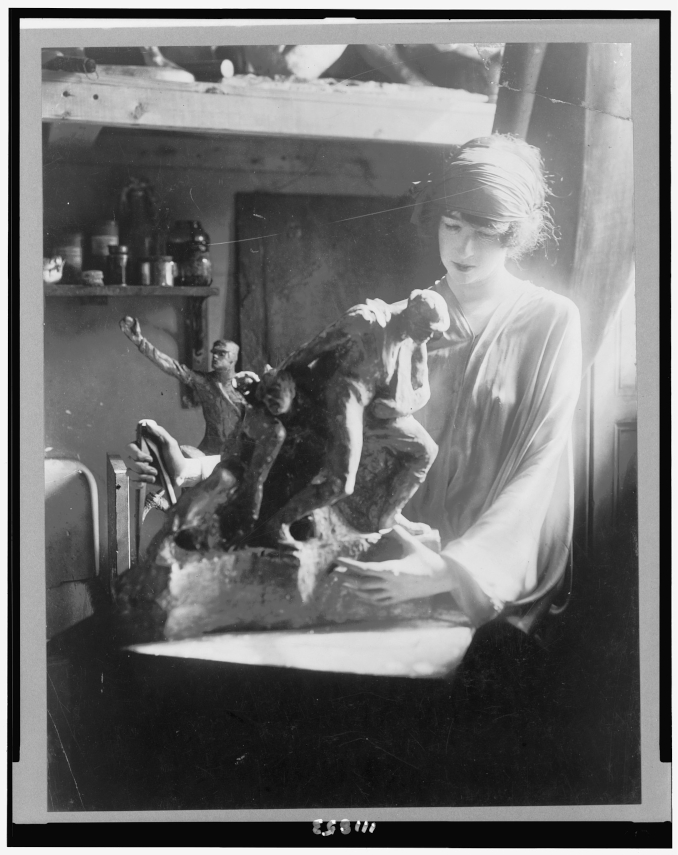

By the time she embarked on this pioneering venture, heiress Gertrude Whitney already had numerous other accomplishments to her name, including as a book author, a WWI hero (for founding a field hospital in France), and an accomplished professional sculptor with statues gracing many public spaces.

Photo of Gertrude Whitney from September 1921 edition of Tatler. Photo: Alfred Cheney Johnston/Wikimedia Commons

As a daughter of the billionaire Vanderbilt shipping family, Gertrude was never “like anyone else.” She was raised fully aware that she was always in the spotlight, with responsibilities that came along with the privileges of wealth. She also was subject to a myriad of conventions (such as not being able to attend her cousin Consuelo’s wedding of the century to the Duke of Marlborough simply because Consuelo’s parents were divorced) and expectations to marry right, attend the correct balls, and be a prominent New York socialite. By age 25, married to Harry Payne Whitney (a childhood friend from a distinguished old family), she had three children, and…a restlessness that led her to study sculpture.

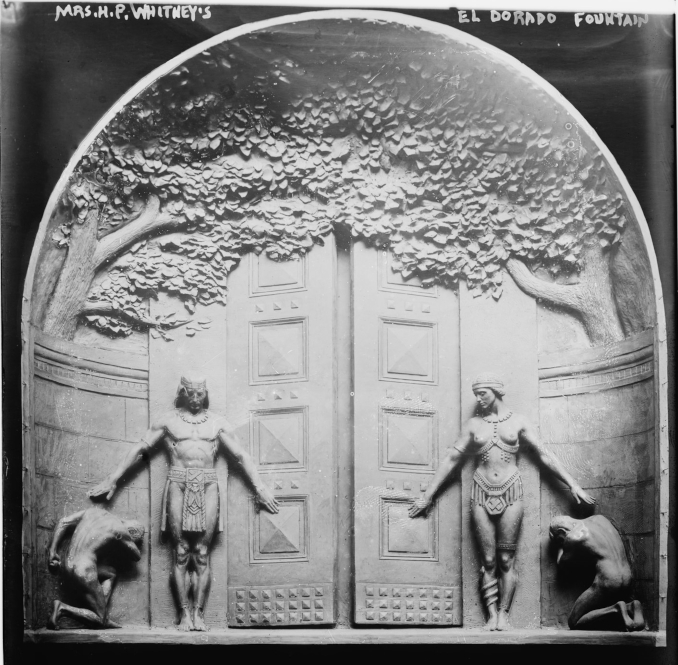

Gertrude Whitney. El Dorado Fountain—photo detail of the sculpture at the San Francisco Exposition, 1915. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By the early 1900s, sculpting and writing travel books took up more of her time than a marriage that had settled into one of convenience. For the next 15 years, Gertrude produced numerous large sculptures, such as the El Dorado Fountain that graced the 1915 World Exposition in San Francisco and the Titanic Memorial. The Memorial, designed by Gertrude in 1914 but not erected until 1931, in Washington, DC, was commissioned as an initiative of women survivors to honor men who died in the Titanic disaster. As the inscription on the monument says, it was dedicated to “the brave men who perished in the wreck of the Titanic, April 15, 1912. They gave their lives that women and children might be saved.” Gertrude’s powerful design of a man stretching his arms inspired the famous pose of the couple on the bow of the doomed ship in the 1997 movie Titanic.

Gertrude Whitney. The Women’s Titanic Memorial, 1931. Washington, DC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While her husband mostly pursued horse breeding, polo playing, and yachting, Gertrude sculpted in all seriousness while also getting involved in many humanitarian causes. One of her causes was supporting the WWI war effort from the start by providing funds of an estimated quarter of a million (in 1914 dollars) to establish a field hospital on the European front. With this gesture, Gertrude wanted to repay the years of happiness that France had given her before the war, when she would spend months each year working on her sculptures at her Paris studio, going to museums, and traveling to French resorts. Her commitment to the field hospital did not just include securing the enormous funds, organizing a team of medical personnel, and shipping supplies to France—she also traveled herself a few times to war-torn France to supervise the hospital’s set-up. In 1926, she completed her last public commission: a statue of an American soldier intended to commemorate America’s support of France during WWI. That symbol of the American-French alliance overlooked a harbor in Saint-Nazaire in Brittany until it was dynamited and destroyed in 1941 by the German army.

Photo of Gertrude Whitney standing with her statue of soldiers, 1920. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the 1920s, Gertrude supported art events and individual artists. She also started dreaming of creating a place where contemporary American painters and sculptors could exhibit their works. At the time, there was little respect or financial recognition for American artists in their homeland. In 1907, for example, when Renoir’s La Famille Charpentier sold to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”) for $18,480, a painting by a living American artist would have fetched only about $1500.

George Benjamin Luks. Armistice Night, 1918. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In those days, supporting the arts also meant supporting artists. Gertrude did it all—including paying artists’ overdue rent or doctor bills, sponsoring trips to Paris, or helping with solo exhibitions. She also set up the Whitney Studio Club, an organization to promote the education, support, and presentation of contemporary artists. In 1916, the first show at Whitney Studio Club was called Modern American and Foreign Artists. Many painters, such as John Sloan and Edward Hopper, had their first shows at the Club. Notably, out of 400 club members, more than a quarter were women artists, at a time when women—artists or not—had a hard time being admitted to many public organizations.

Edward Hopper. New York Interior, 1921. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Being an artist herself, Gertrude was more than a rich collector of art—she bought the works of new artists, and she opened the doors of other galleries for many debutants. By 1929, she had a serious collection of about 600 works and a mission to make them known to the American public. But when she offered her collection to the Met, even proposing to endow a special wing to house it, the museum’s director Edward Robinson immediately refused the offer, since the American art did not rate high enough in his eyes. Out of that refusal was born the Whitney Museum of American Art.

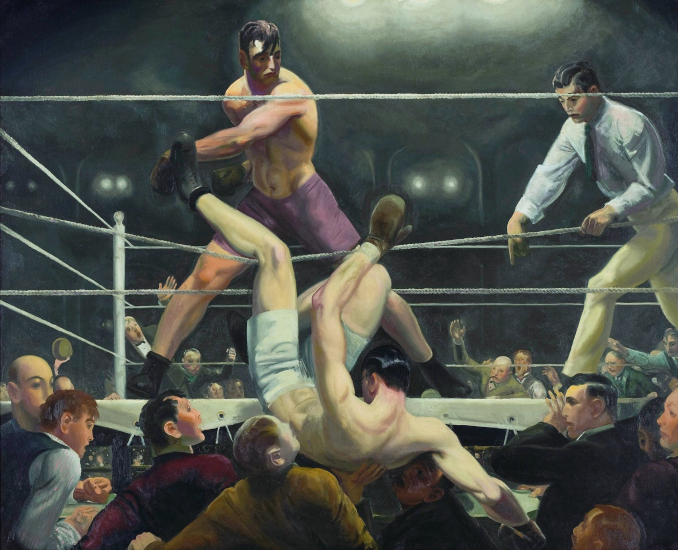

George Bellows. Dempsey and Firpo, 1924. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Whitney Museum’s beginnings were modest. Although several thousand guests showed up for the opening, the initial collection reflected Gertrude’s personal preference of realist paintings and included few of the future greats of other styles in American art. With the museum’s creation, a first step was taken, however—for the first time, there was concrete recognition that American artists deserved their own dedicated institution, even while all other New York museums were still filled with mostly European art.

Edward Hopper. Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Gertrude’s legacy was not only the founding of a museum that no one else deemed it worthwhile to establish; she also ensured that her daughter and granddaughter would continue her commitment. Her devotion to a museum as a focal point for artists was also reinforced by the fact that the first three curators of the Whitney—Edmund Archer, Karl Free, and Hermon Moore—who served all the way until 1958, were artists themselves.

Thanks to generations of Whitney women, the museum has continued to thrive. First, there was Gertrude, who had the idea to create one place devoted to American artists and the fortitude to carry out this idea. Then there was her daughter, Flora Whitney Miller, who not only maintained the museum’s mission but also, resisting financial pressures, declined to have the Whitney folded into the Met in 1948; instead, she expanded the museum’s gifting policies to enable artists, patrons, and trusts to endow the Whitney with more art. Her daughter (and Gertrude’s granddaughter), Flora Miller Biddle, continued on the board of the museum and presided over the creation of the new Bauer Building. Meanwhile, the museum evolved in many ways, changing location a couple of times, moving from collecting primarily realist art to acquiring all new styles and genres (which brought the museum exciting modern art masterpieces ranging from Abstract Expressionist to Pop and Post-Modern), and increasing its collection to the current 25,000 works.

View of the Whitney Museum of American Art from Gansevoort Street. Photo: Ed Lederman, 2015.©Whitney Museum

Today, the Whitney Museum of American Art is firmly established as one of the most exciting and beautiful world depositories of modern art, but it is often overlooked that this supermodern building on the Hudson River had its modest beginnings in the vision of one woman—Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.