Protest in Art

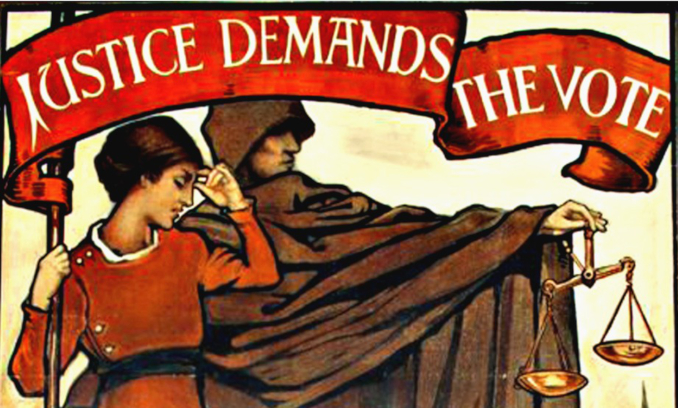

Poster for the Suffragette movement. Mary Lowndes (1909). Published by Brighton and Hove Women’s Franchise. Artists’ Suffrage League. Photo: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

If an individual stands up to bullies or resists violence, it is called personal courage. When a group does it, it is often called a revolution, a social protest, or a war of independence. Art has either illustrated examples of such resistance or sometimes it has served to incite it.

Here are some stories of both such functions of art.

French artist Jacques Louis David had the misfortune of finding himself constantly caught in between opposing social forces. He started out as one of the most talented proponents of the neoclassical style that moved French art from the Rococo’s fluff to clean lines and historical subjects, but he struggled against the bureaucracy of the Royal Academy. His fervor for social change and moral renewal found its outlet when the winds of history deprived the reigning King Louis XVI of his head and filled the streets of Paris with revolutionary crowds. David was closely aligned with the new power, embodied by Maximilien Robespierre, an early leader of the French Revolution, who unfortunately soon followed the king to the guillotine. David ended up in prison for several years, but Napoleon’s rise to power eventually saved him. He became a court painter, reaching the height of his political and artistic career, only to lose influence (again!) with the Bourbon restoration. He died in exile in Brussels, having finally realized that being an artist was a better deal than being a politician.

David painted The Intervention of the Sabine Women during his imprisonment after Robespierre’s demise. After having almost lost his life, he created a conciliatory message about the need for peace. The experience of the French Revolution’s brutality mellowed him to the point that he portrayed a victory of loving women over murderous men in the heat of a battle. Hersilia, the wife of Romulus (the legendary founder of Rome), runs into the battlefield with her babies, separating her Roman husband from her father, the Sabine tribe leader. In mythological or religious paintings, women and children usually would have been cast as victims, but here we have an image of women in fearless and effective action. You can see that one of the warriors is already sheathing his saber, and other men will soon also capitulate to Hersilia.

Jacques-Lois David. The Intervention of the Sabine Women,1794-99. Oil on canvas. The Louvre. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Jan Matejko was the most famous representative of historical painting in 19th-century Poland. He lived during the period when Poland had already spent almost a hundred years erased from the world map by subsequent partitions of the country by Prussia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Russia. His huge historical canvases had a patriotic mission—both raising the national morale and cautioning against political mistakes. This painting, which shows the protest of a lonely patriot—Tadeusz Reytan—against the destruction of his nation, is familiar to any school kid in Poland. Reytan was an 18th-century member of parliament who opposed the shameful collaboration of some corrupt senators with foreign governments. In this scene, Reytan is trying to block with his own body the legislators who are exiting the Sejm (Polish Parliament) after having voted for the country’s political destruction. After that event, Reytan became Poland’s symbol of a lonely patriot who resists the loss of political sovereignty.

Jan Matejko. Reytan at Sejm 1773, 1866. Oil on cavas. The Royal Castle, Warsaw. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

History tends to repeat itself, and in the case of Poland, it has been repeated for over a thousand years—there has always been one power or another invading that flat and fertile land. In the 20th century, stuck behind an Iron Curtain, post-war Poland underwent several political revolts that culminated in the birth of the Solidarity movement. The fall of communism in Poland was sealed on June 4, 1989 through the first free, unfalsified national elections since the country was overrun by the Red Army in 1945. The election campaign pitted the state propaganda machine (which owned all the printing houses, all physical materials like paper and paint, and all the cherry pickers to hang banners) against ordinary citizens who had more patriotic fervor than paint. In this context, Tomasz Sarnecki, a student of the Academy of Fine Arts, came up with an election poster that became a symbol of that election and of Solidarity’s victory: a stylized image of Gary Cooper from High Noon, walking toward an election urn. It was a call to arms—go vote for a final showdown. This historical moment—an overwhelming victory of a democracy—became immortalized in this poster, replicated in media worldwide ever since.

High Noon June 4th, 1989. Tomasz Sarnecki. Replicas of the poster were displayed in front of the Presidential Palace in Warsaw in June, 2011. Photo: Wistula at Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

In this particular photo taken in 2011, replicas of the original poster were displayed in front of the Presidential Palace in Warsaw. The posters are flanking a statue of Prince Józef Poniatowski, a famous general who led the Polish army in wars of insurgency against Austria and Russia in the early 19th century. In a way, this photo sums up the history of Poland—a nation of repeated fights for independence.

The 19th century was a great time for historical paintings. Masters of this genre, like Matejko, would often turn to immortalizing significant moments in their nation’s history. In Russia, the most renowned artist of that period was Ilya Repin, whose realistic yet romantic brushwork lent itself well to narrative paintings depicting episodes from his nation’s past. Repin’s canvas called Zaporozhian Cossacks Replying to the Turkish Sultan is not only one of the most known historical paintings in Russia (there are two versions) but also a delightful wink to the audience. Repin represented here a (most likely apocryphal) story of a supposed exchange of letters between fiercely independent, horse-riding tribes of Cossacks from the Ukrainian steppes and the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet IV. Apparently, during a military campaign in 1672, the Sultan sent a self-important and contemptuous missive demanding a surrender. The wild cavalrymen wrote back a refusal full of insults and profanities. A purported copy of this letter was read in Repin’s presence, inspiring him to pick up his brush.

Ilya Repin. Zaporozhian Cossacks Replying to the Turkish Sultan, 1878-91. Oil on canvas. State Russian Museum. St. Petersburg. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Repin captures a moment when the Cossacks (the cowboys of the eastern steppes) are coming up with the grossest insults they can muster, and they are having a ball doing it. Artistically, it’s a still from a movie scene—with picturesque characters and vivid expressions and gestures—you can almost hear the ribald laughter. A few decades later, you could have filmed this scene instead of recreating it in paint. The artwork was immediately purchased by Tsar Alexander III for his imperial collection. The fierce and freewheeling Cossacks embodied, for both the Tsar and the rest of the nation, a patriotic resistance against foreign invaders and a different religion.

In the 20th century, various kinds of resistance movements multiplied: wars of independence, the rise of terrorism in prerevolutionary Russia, workers’ protests against bad conditions in European factories, anti-war protests before and during both great wars, and political agitation for and against every ideology in existence. One protest stands out in the history of personal freedom—women’s suffrage. It started in Victorian England, and by 1872 it had become a national movement, gaining momentum in the early 20th century but suspended during WWI—and not fully succeeding until 1928. That covers generations of women who never saw equalization of their rights in their lifetimes.

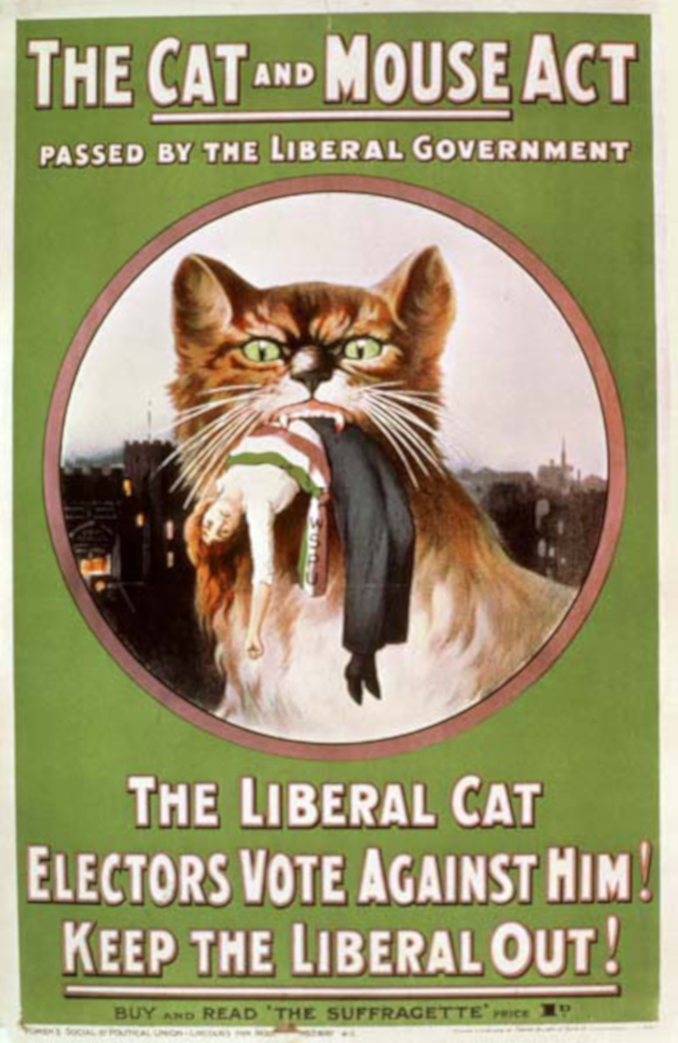

One of the infamous moments of the suffragettes’ struggle was the “Prisoners Act” passed by the British Parliament in 1913. It was commonly called the “Cat and Mouse Act,” referring to cats’ propensity to catch and release mice. The mice in question were the suffragettes, who would be released from prison during their hunger strikes, only to be incarcerated again when they got better. The Museum of London has in its collection a poster that protests this parliamentary act of Lord Asquith’s Liberal government. Satirical and funny though this poster may be, it actually calls attention to the despicable cruelty of lawmakers. Women had no vote, so all they could do was distribute such posters.

Cat and Mouse poster. 1914. Museum of London. Photo: Women’s Social and Political Union… Photo: Wistula at Wkimedia Commons

A picture is worth a thousand words, they say. A good picture is probably worth even more, and artists throughout the centuries have been well aware of the power of their images. Not all of those images were memorable, but the ones above have stayed in the history of art for good.