Food for the Soul: Global Trade in Art – Part 1

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

There are bigger world problems than this, but you may have noticed that your favorite sheets are not in stock at Ikea—it is the global trade disruption, compliments of the pandemic. As “out of stock” notices affect our ability to obtain our favorite snacks, shoes, a sofa or a mouse trap, the whole world suddenly has sat up and noticed that global trade is something that makes our world go round. We used to take it for granted—coffee from Sumatra, pens from Japan, cheese from Switzerland—everything available anytime, at any place.

Although global trade intensified in our modern era, it has actually been going on for millennia, spurring technological developments and intellectual exchanges of ideas, as well as causing countless wars. Trade exchanges have also seeped into art—sometimes as luxury décor ostentatiously displayed in Dutch Republic canvases, and sometimes as images of exotic lands or animals shown in book engravings.

This series is devoted to parts of the world that, through trade, have left indelible traces of their culture in artistic representations.

We can start by looking at The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds, which is one of the most popular artworks at the Louvre, painted by master of candlelight Georges de La Tour in 1635. In this picture, the players are playing the so-called “Polish bank” card game and. . . one of the men is clearly cheating. He is being aided by a woman who probably organized the game, ensnaring “the mark”—a sumptuously dressed youth—who seems to be oblivious that the deck is stacked against him. But we can ignore the action in favor of examining the clothing and props used by de La Tour to paint this scene. The woman who organized the game is wearing multiple strands of pearls, possibly harvested in Venezuela (Columbus discovered immense pearl beds off Venezuela’s Paria peninsula in 1498), while her clothing’s silk could have come from China; the collar embroidery looks Indian, the ostrich feathers were perhaps from Africa, coral in the bracelet would be Italian and the wine could be from Spain. In its own way, this picture sums up the extent to which traded goods from other continents had penetrated into European daily life. The painting would not look the way it does without global trade.

Part 1. Going to the Far East

Silk production and trade are as old as the Chinese empire itself, and certainly by the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) it was one of the main goods traded with both surrounding (and threatening) nomadic tribes as well as foreign kingdoms—in the latter instance, the silk trade provided a means of securing a flow of goods otherwise lacking in China. The original scroll of Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk was painted by a Tang dynasty artist named Zhang Xuan around 635 AD, but the long tradition of copying revered art and literary works produced various copies of this work. The copy above, Women Preparing Silk, was most likely painted by the Song dynasty emperor Huizong, who was renowned for his mastery of calligraphy and art.

Transforming the secretions of the silkworm into a smooth and shiny fabric requires many labor-intensive stages—boiling, bleaching, rubbing with a stick, pounding, and ironing—and the entire 6-foot-long scroll features all these stages of silk preparation. The detail above shows women ironing with a copper iron. These are court ladies, not the regular workshop workers, so they are gracefully posed and dressed in colorful, intricately patterned silk robes.

Silk played a crucial role in China’s international trade and domestic economy. Mongol steppe tribes could be appeased with vast amounts of silk rolls, while Sogdian and Persian tribes might be offered silk in exchange for horses and luxury goods. The troops guarding the borders were as often paid in silk fabric as in grain. The luxurious fabric was both currency and a way to bring to China those goods that could not be produced locally.

The most desirable of these “unobtainable goods” were the “flying horses.” We know what they looked like from literary descriptions but especially from Tang dynasty statuettes found in tombs. These large-bodied, strong, and graceful horses were the objects of desire of every emperor and aristocrat of the Tang and Song dynasties in China and inspired countless poems and sculptures. Regular Asian horses were small, pony-like creatures from the steppes. There was, however, another kind—those large horses raised in the Fergana Valley in Central Asia (today’s Tajikistan and Afghanistan), which were brought along the Silk Road trade routes to China. They were called heavenly horses (tian ma 天马) and they were said to sweat blood (on account of a characteristic red perspiration). As the mounts of aristocratic and imperial riders, they represented as desirable a means of transportation as a Ferrari would today, bestowing elite status on the rider. This is what is depicted in the clay statuette above—the silk-robed lady is clearly a noblewoman whose high status is underscored by the heavenly horse she is riding.

These rare animals would be brought to China alongside the well-worn routes of the Silk Road, through the mountain pass and valleys of central Asia. Here is another Tang dynasty portrayal of a Fergana Valley horse, ridden by an imperial soldier, whose higher rank is indicated precisely by the type of horse he is riding.

Western trade with China, famously evidenced by the adventures of Marco Polo in the 13th century, gave birth to China’s mass production of goods, especially porcelain, specifically for the European markets. When in 1998 fishermen uncovered a shipwreck of a Chinese junk traveling from Canton (today’s Guangzhou) to Batavia (today’s Jakarta), a salvage operation uncovered about 130,000 pieces of mass-produced ceramic. In the Vermeer painting above, there are actually two important objects—the titular pearl necklace with pearls brought over from the South Seas and on the left a barely visible Chinese porcelain jar. The craze for Chinese porcelain started in the Netherlands after a Dutch ship brought over, in 1602, the porcelain goods seized from a Portuguese treasure cargo. Afterwards, the Dutch could not get enough of Ming pottery, especially the white and blue kind.

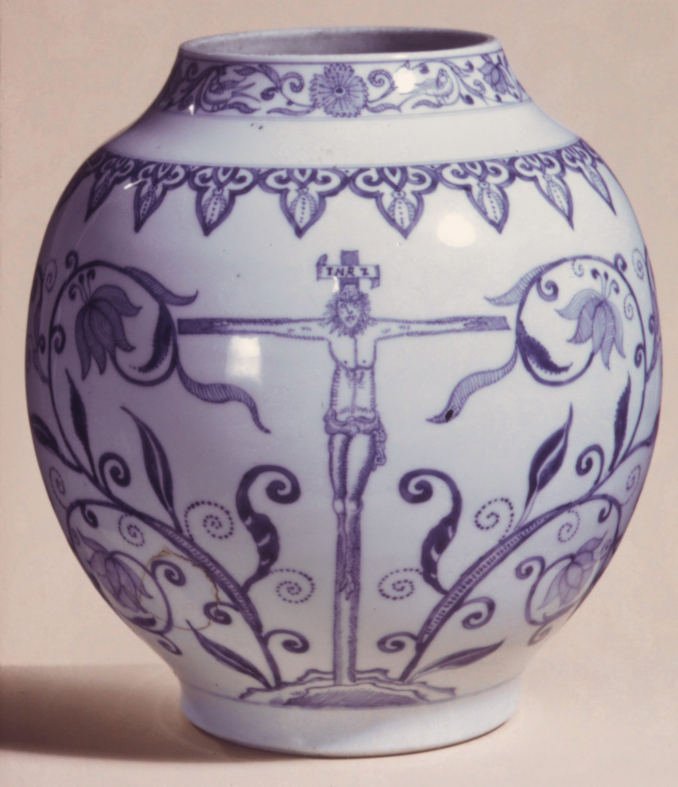

This 17th-century jar is an example of ceramic clearly produced for the European market; moreover, it bears the traces of an awkward copying of western decoration to please the overseas customers. The floral ornament on the jar suggests it was a copy of an embroidered fabric, perhaps from a book cover or a cloth. There were (and still are) entire factories in China devoted to making porcelain for export. Initially, these items were decorated in purely Chinese colors and patterns, but as the global trade grew, there was more customization of vases and plates to satisfy European fashion trends and color preferences. For example, the Ming dynasty porcelain with its thick white glaze and no external painted decoration was dubbed in the West, blanc de chine. Another type of white and lapis-blue porcelain inspired the famous Delft ceramics. Until the discovery of kaolin clay processing in 1708 in Saxony, beautiful white ceramic had to be imported from China. Afterwards, production of copies of the Chinese “white gold” was initiated throughout Europe in royal manufactures like the ones in Sèvres, Meissen, or St. Petersburg. The so-called chinoiserie porcelain (especially rococo vases and figurines of shepherds and courting couples) appeased Europeans’ hunger for pottery and knick-knacks, at the same time reducing the financial imbalance of Western kingdoms in their trade with the Far East.

European monarchs went to great lengths to combat the thirst for fashionable goods and reduce their foreign trade debt. Jean-Baptiste Colbert (the finance minister of King Louis XIV) oversaw the set-up of fabric and ceramic workshops, as well as retaining and training craftsmen precisely to control the volume of imported goods. Centuries later, when France was importing muslin from India through France’s enemy England, Napoleon tried to reduce the demand for cotton muslin among his court ladies. After his ascent to power in 1799, he mandated the fashion for silks (produced in Lyon) and wool, while commanding a lowering of palace heating to force women into warmer clothes. He also ordered formal (silk) clothing for attendance at state functions. Napoleon was not always successful, however—sometimes women would just put on shawls and wear diaphanous muslin anyway. For example, François Gérard, a key artist of the Empire period, painted Catherine Verlée, the wife of the all-powerful Prince de Talleyrand, wearing a fashionable gown à la grecque. These antiquity-inspired high-fashion dresses were made of the thinnest of muslin, designed to cling and reveal as much of the body as was decent. After Napoleon’s insistence on women wearing silk, a lot of dresses also ended up in a compromise. Madame Talleyrand is wearing a silk gown with just an overdress of chiffon (possibly muslin) but. . . the pashmina shawl on the chair has Indian embroidery in paisley patterns.

Automatons, clocks, and any kind of mechanical precision contraptions—including large and detailed world globes, armillary spheres, and nautical instruments—were the 18th-century equivalent of today’s smartphones and consumer electronics. Only the aristocracy and royalty could afford the most complicated machines, but they created a demand for such objects not only in Europe but also at the wealthiest houses of royalty and nobility in other parts of the world. Goldsmiths, engineers, and clockmakers were more than happy to oblige. The gold clock and automaton creation of James Cox pictured above was expressly manufactured for the imperial court of China. Britain’s East India Company, one of the most successful multinational corporations, commissioned it as a present for the Qing dynasty emperor Qianlong, who presided over one of the most stable eras of Chinese history. This is an example of a reverse flow of goods—Europe sending something to China, in this case as a diplomatic present intended to smooth the way for trade relationships. At the time, the European trade imbalance with China was enormous. In the decade between 1771 and 1780, the East India Company imported six million pounds of tea from Canton—one-third of all the tea that China was exporting to Europe.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC is the Dutch acronym) was the other global trade powerhouse in Europe, and through this enterprise, the Netherlands got into tulips from the Ottoman empire, pearls from the Pacific, sugar from Formosa (today’s Taiwan), porcelain and tea from China, spices from what is now Indonesia, and all the other goods that sustained the growth of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch obsession with exotic flowers, which culminated in the first-ever speculative market bubble in 1637, is expressed perfectly in the lives of painter Ambrosius Bosschaert and his sons, who specialized in portraying the novel tulip flower. The painting above, Flowers in a Chinese Vase, is a perfect example of a Boscchaert composition—a beautiful, centrally positioned vase with huge and colorful flowers. Bosschaert was one of the first artists who treated these showy bouquets as stand-alone subjects of paintings. He made a portrait of them, as if they were important people. They may not have been people, but they were very important—those sought-after flower compositions were status symbols. Bulbs of rare tulips were collectible and an object of financial speculation. But Bosschaert’s painting also features other precious status symbols, such as the beautiful vase from the Ming dynasty’s Wanli period, which was so prized that once it got imported to Europe, it was set with a gilt-silver top ring. The shells strewn around the vase come from the Indian and Pacific oceans, which, again, were objects of high value and rarity. Year after year, the VOC ships would haul an enormous amount of these precious and exotic objects, which went on to decorate the homes of ordinary burghers, even if sometimes only through a painting like the one above.

Pietro Longhi’s painting The Rhinoceros documents another type of trade. . . that of exotic creatures. This Venetian painter specialized in genre paintings of scenes observed in his city—street performances, masked balls, games and concerts—as well as paintings of novelties such as chocolate drinking (another fashionable trade good) and exotic animals. He painted two versions of this display of a rhino’s visit to Venice (another version is in London’s National Gallery). This is a portrait of Clara, an unfortunate rhinoceros captured in India and brought by the VOC to the Netherlands. The Company’s director, named Van der Meer, bought her in 1741 and took her on a grand tour of European capitals. In the course of her peregrinations, Clara got addicted to beer and tobacco leaves and, in 1750, lost her horn (in the painting, her handler is holding up the horn to show the public). Clara’s owner made a fortune from admissions and selling rhino merchandise, received a nobility title, and was offered 100,000 écus by France’s King Louis XV. Poor Clara finally passed away in 1758, apparently after eating some bad bread in London. Traders would bring exotic animals to royal courts and private zoos—monkeys, lions, parrots, even giraffes—as part of their shipments of more mundane cargo of tea, coffee, or sugar. In 1826, a ship from Cairo brought to Marseille a giraffe sent as a diplomatic gift by the Egyptian ruler Mehmet Ali to France’s King Charles X.

Clara was a sensation wherever she went, and Longhi’s painting reflects this by showing a group of gawkers who paid to be seated in circus-like seats. But this is not a photograph and Longhi, whose paintings are often mildly satirical, captured something else—the contrast between the world of nature and that of artifice. There is Clara—an impossibly shaped unique mystery of biology—and there are the elegant viewers, who look grotesque in their carnival masques, tricorne hats, and voluminous clothes. Objectively, they look just as exotic and unnatural as the poor animal.

These works represent but a small fraction of art reflecting the incessant flow of goods into European kingdoms, especially those that had maritime capacity, enriching the nations and transforming tastes and knowledge for centuries to come.