Food for the Soul: Comets – Looking Skyward for Inspiration

The Comet of 1680 over Rotterdam. Lieve Verschuier (1680). Rotterdam Historic Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

“As above, so below.” ~ Hermes Trismegistus (6th century AD)

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

A sudden appearance in the night sky of an exotic shape of a ball and a shiny tail would be hard to ignore. Over millennia, people have considered comets an omen—either a good sign or a bad one, but never something to be disregarded. How do we know that? We know because, from antiquity on, there are written accounts of comets’ appearances and numerous artistic records made in stone, wool thread, or oil paint.

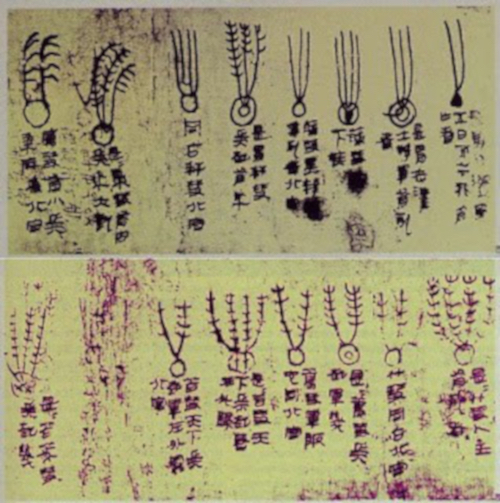

One of the earliest such records comes from China’s Western Han Dynasty (202 BC – 9 AD). The 1972 discovery of the Mawangdui tombs in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province and the heartland of China, has been hailed as one of the greatest archaeological finds ever. Not only did the tombs contain a perfectly preserved mummy of Lady Dai, the wife of the provincial ruler, but there was also a treasury of artifacts from about 180–160 BC. Lady Dai was buried with cosmetic boxes, jewelry, silk dresses, lacquered serving dishes, furniture, bronzes, and tapestries—all immaculately preserved. A nearby tomb of a man who was possibly her son contained weapons and jewelry, but also…books. A lot of books. The texts, written on bamboo slats and silk scrolls, include treatises on mathematics, warfare textbooks, religious discourses, poems, military maps, and astrological research. In the latter category, one document (dated to being prior to 168 BC) depicts 29 different comets, including the names they were given, their shapes, and associated portents.

Astrology manuscript. 2nd century BC. Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha, China. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Chinese historic documents illustrate a firm belief in the role of comets as portents of good or bad luck, especially for the rulers. Comets were believed to be a proof of an imbalance between yin and yang, and they were carefully monitored by palace astronomers. In fact, those detailed astronomical records from ancient China have enabled modern scientific orbit calculations of about 40 different comets.

The Tang dynasty Emperor Ruizong, who lived in the 8th century AD—a time when Islamic invaders were attacking the Iberian peninsula and Gaul, and the Vikings had started raiding European coasts—was a ruler who bowed to comets’ significance. This colorful period of Tang dynasty history was marked by brutal palace coups, intrigues by empresses, and regicide that would put Shakespeare’s imagination to shame. Emperor Ruizong, with a reign repeatedly interrupted by coups and various betrayals and power grabs, ended up abdicating, apparently after the appearance of a comet in 712 AD. Modern historians believe that he may have simply been worn down by the constant palace infighting, but certainly a bad celestial omen could have been an additional argument supporting his decision.

Medieval Europeans were not much different from the medieval Chinese in this respect. They observed these fiery apparitions with foreboding and assumed that there must be a connection between the show in the sky and their life on Earth. When Halley’s comet appeared in April 1066, people were not aware that this comet is the only one that is regularly visible on Earth to the naked eye and is a periodic comet, reappearing about every 75 years. (The astronomer Edmond Halley would not determine this fact until 1705.) Thus, all the 11th-century Anglo-Saxon and Norman fighters knew was that a fiery celestial object had burst into the night sky, presaging tumultuous times.

Panel from the Bayeux Tapestry featuring Halley’s comet of 1066. (ca. 1070). Bayeux, France. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

They were soon proven right about major events, for the Battle of Hastings was coming. The battle was part of the succession war between Harold, Earl of Wessex, who was an Anglo-Saxon heir-apparent, and a Norman prince named William of Poitiers. William, later dubbed “the Conqueror,” invaded England at Hastings and won the battle on October 14, 1066, establishing a new dynasty in England and creating a future reason for centuries of conflicts between England and France. Harold was slain in battle, and it was believed that the comet foretold his demise. The Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts all the events leading to the battle, was commissioned by bishop Odo, William the Conqueror’s half-brother. It includes a multicolored embroidery of the comet, streaking its fiery tail of doom above the heads of the awed people.

Halley’s Comet embroidery in the Bayeux Tapestry. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Giotto di Bondone can be credited not only with being one of the greatest Italian artists who pushed artistic style from the Byzantine Gothic toward the Renaissance but also probably as the first artist who realistically painted a comet. In his fresco, Adoration of the Magi, Giotto featured the image of Halley’s comet of 1301, which he must have seen with his own eyes, as “The Star of Bethlehem.” To render the comet’s pulsing radiance, Giotto applied gold pigments and painted in vivid orange streaks coming out of the ball of the coma (stream of gas around the front of the comet). Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, where this fresco is located, is decorated by dozens of New Testament scenes that are considered Giotto’s highest artistic achievement. In honor of Adoration of the Magi, a robotic probe from the European Space Agency that was the first to fly close to Halley’s comet in 1986 was named Giotto.

Adoration of the Magi (featuring Halley’s comet of 1301). Giotto di Bondone (1301-04). Scrovegni Chapel, Padua. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

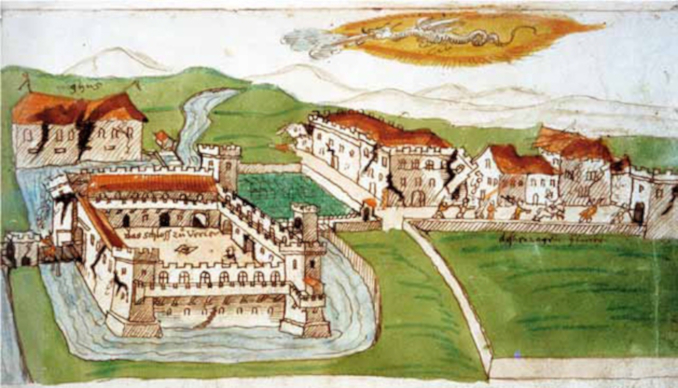

Comets did not have a very good reputation in the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. They were at least associated with, if not presumed to be directly responsible for, all kinds of natural disasters and ills—the plague and earthquakes included. This is evident in a 16th-century illustration of a 1570 earthquake in the Italian city of Ferrara, which shows a comet in the sky (which would have been the Great Comet of 1577). This appears to indicate that Ferrara’s destruction and subsequent economic decline were blamed retroactively on the passage of a celestial beast seven years later—or at least the comet is a symbol of the misfortune that befell the city.

Ferrara Destroyed by the Earthquake of 1570. H.J. Helden (ca. 1577). Zurich University Library. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Unlike Halley, the Great Comet of 1577 was a non-periodic comet that passed close to Earth and was visible all over the continent, causing both anxiety among the population and scientific excitement. A Czech woodcut bears the following inscription by Peter Codicillus of Tulechova: “About a terrible and marvelous comet as appeared the Tuesday after St. Martin’s Day (1577-11-12) on heaven.”

The Great Comet of 1577 Seen at Prague. Jiri Daschitzsky printshop (1577). Zentralbibliotek Zürich. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The 1577 comet was studied by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. The age of scientific observation had arrived in Europe and, popular fear of comets notwithstanding, the astronomers were on their way to examine the sky phenomena with a discerning eye and newly designed instruments. Interestingly, an eminent Arabic astronomer named Taqi al-Din also studied the same comet in detail. Unfortunately, Sultan Murad III considered the comet to be a bad omen and the cause of a plague outbreak. As a result, Taqi al-Din’s famous laboratory was closed, and his achievements in astronomical research did not become as well known as Brahe’s scientific contribution, despite the fact that al-Din’s instruments are believed to have been more precise. Brahe is credited with discovering that a comet’s head always faces away from the sun.

The Astronomical Observations: the Comet. Donato Creti (1711). Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

At the dawn of the 18th century, later dubbed the Age of Enlightenment, Italian Count Marsili was trying to get papal funds to build an observatory in Bologna. He first had an observatory built on his ancestral grounds. However, his family strongly opposed such newfangled ideas, including his plan to donate the palazzo to the city of Bologna, so he turned toward the city senate and the Vatican. The count then commissioned Donato Creti, a young Rococo painter in Bologna, to paint eight nocturnal landscapes to which a miniaturist added images of the five known planets, the sun, the moon, and a comet—presenting them the way they would have been seen through a telescope. For instance, the painting of Jupiter shows six bands on the planet’s surface. Creation of these planetary “portraits” was supervised by mathematician Eustachio Manfredi, who was, as we would say today, a “scientific advisor” to the project. About a decade earlier, in 1702, Manfredi would have seen two comets crossing the sky, and the comet painting is likely based on his sketches of these celestial events. Count Marsili then sent the eight finished paintings—the equivalent of a PowerPoint presentation today—to the Vatican, and his marketing ploy worked. Funds were granted, a Science Institute was established in 1714, and in 1725, Bologna gained an observatory. It is not certain how the family felt about losing out to planets and a comet.

Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30 pm 5 October 1858. William Turner of Oxford (1858-59). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Donati’s comet was named after its first European observer, Giovanni Battista Donati, who spotted it on June 2, 1858. This comet was one of the brightest in the 19th century and had the scientific honor of being the first to be photographed (photography had been in use since 1839). Donati’s comet appears in numerous artistic records, one of the most popular being the one above by William Turner. Although he is called William Turner of Oxford to distinguish him from his much more famous contemporary J.M.W. Turner, this artist was a very accomplished watercolorist as well. He spent most of his life in and around Oxford, and this is where he observed the comet, recording the time very precisely in his watercolor entitled Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30 pm 5 October 1858. Although the painting’s “scientific” title reflects the fact that by the mid-19th century, comets had become less augurs of fate and more of a scientific curiosity needing to be monitored, recorded, and studied, Turner’s rendition was nonetheless more artistic than accurate. It seems it was more an opportunity to enliven a landscape with a dramatic arc over a valley he must have been observing from a hillside.

Pegwell Bay: A recollection of October 5th>. William Dyce (1860). Tate, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

The “scientific” approach to portraying comets is evident in William Dyce’s Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5th. Again, the title is very precise and matched by the Pre-Raphaelite style of heightened realism. It feels like a color photo, except that in Dyce’s time, photography was in its infancy and certainly not in color. The comet’s scientifically documented appearance serves here as a “time stamp” for a moment in the life of the artist’s family, but it is equally an expression of his ideas of spirituality and time. If the comet represents the celestial (that is, divine or at least spiritual) aspect of human existence, then the beachcombers embody the scientific side of human experience—as they gather shells and fossils among the cliffs that have witnessed geological eons. Pegwell Bay Beach is the location of both Roman invasions by Julius Caesar and thus an important historic marker. This famous beach becomes a meeting point of an impressive celestial phenomenon, a marker of the transitory presence of visiting humans, and the immutable solidity of ages past represented by the cliff face. This painting is considered Dyce’s masterpiece, not only thanks to his artistic skill but precisely because it can be viewed either as a realistic record of an astrological event or as an allegory of passing time and the place of humans in it.

Comet (Night Rider). Wassily Kandinsky (1900). Städlische Galerie Munich. Photo: wikiart.org Public Domain

For artists in the 20th century—a time full of political upheaval and technological acceleration—comets were great symbols signaling change, the mystery of the cosmos, or unexpected events. As photography took over, art found itself rid of the burden of faithfully depicting comets. An artist did not need to record an actual viewing anymore, with that task given over to photography, but he could still use the comet’s alluring shape to inspire. Wassily Kandinsky painted Comet (Night Rider) in 1900—at the turn of a new century and in transition from one style to another.

Kandinsky had several distinct periods in his art, moving from post-Impressionism through the German Expressionism of the Blue Rider group that he co-founded, and all the way to the abstract art for which he is so famous. In Comet (Night Rider), there are still references to the sinuous Art Nouveau style and neo-Romantic notions of a horse-riding knight, but the vivid, contrasting colors, simplified rendering, and mysterious comet that dominates the sky belong to 20th-century style and thought. While Kandinsky’s contemporaries were still creating realistic and fussy compositions, he was already far into what we now consider “modern art.” His comet is not a scientific record but, as in the Middle Ages, a symbol—perhaps not the symbol of doom, but a symbol of mystery and the cosmic forces that guide people.

In the 21st century, we have come to understand comets’ recurring nature and scientific structure, and comets are less scary and mysterious. Here is a real image of Comet Neowise, which streaked through our night skies in 2020. For both artists and regular people, we now have the freedom to consider comets as beautiful decorations of the night-time sky, symbols of unimpeded movement in space, harbingers of change—or sources of inspiration.

Comet Neowise on July 14, 2020. Photo: SimgDe at Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

“Before the Earth was formed, there were comets here. Afterwards, and for all subsequent eons, comets have graced our skies. But until very recently, the comets performed without an audience; there was, as yet, no consciousness to wonder at their beauty. This all changed a few million years ago, but it was not until the last ten millennia or so that we began to make permanent records of our thoughts and feelings. Ever since, comets have left a good deal more than dust and gas in their wakes; they have trailed images, poetry, questions, and insights.”

~ Carl Sagan and Anne Druyan, “Comet”