Food for the Soul: Faces of Tuscany

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

In Florentine museums and churches, there is an endless parade of Madonnas and altar compositions of the Holy Family, which have somewhat lost their religious impact after so many centuries of changing spiritual views. When they are displayed en masse in art galleries, what makes the most immediate impression are those details that have withstood the test of time. The best are the unusual, expressive faces that suddenly pop out of the gilded frames.

Despite pandemic travel turbulences, L’Uffizi is still full of tourists crowding in front of Botticelli’s Primavera and da Vinci’s Annunciation—paintings that remain more breathtaking and larger and more vivid than any illustration can render. Among these perennial favorites also hang some less popular ones, like the Madonnas by Filippo Lippi.

Just take a look at Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels. It portrays beatific Tuscan faces in vibrant colors that have held up much better than many 15th-century masterpieces painted in early oils that tended to lose their pigments (especially the blue). Lippi lived earlier than the masters of the High Renaissance and used tempera on wood; that medium has held fast until our time.

As the artist who taught Botticelli, Lippi could tease an angelic look for his John the Baptist directly out of heaven, as evidenced by the face of John the Baptist from Lippi’s Adoration of the Child with the Saints. One of the lesser Medicis, Piero the Gouty, commissioned this from Lippi for a private chapel.

Here is another idea of John the Baptist’s face by Gherardo di Giovanni from an altar painting with a long museum title: Madonna and the Child Enthroned with St. Francis, a Sainted Bishop, St. John the Baptist, and St. Mary Magdalene. The face of St. John the Baptist looking at Mary Magdalene is that of a concerned young man who is relating to the woman standing next to him. This is a very Renaissance painting concept—people interacting with each other rather than staring into space.

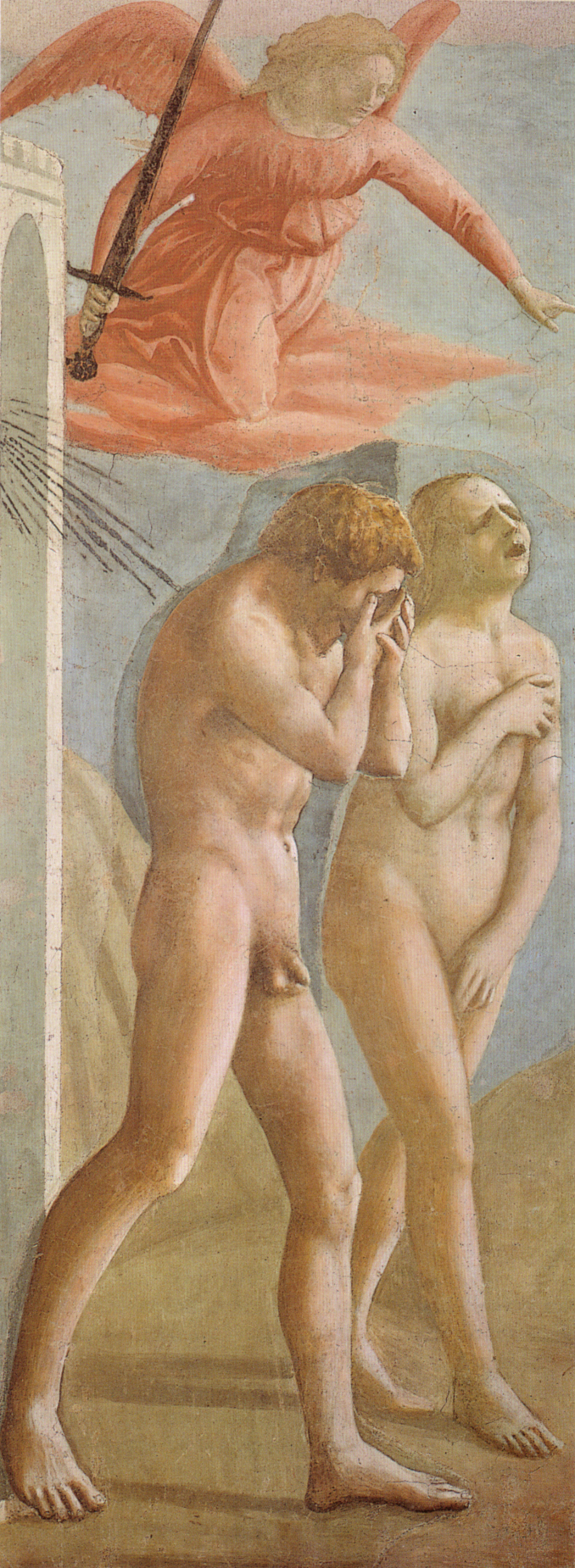

As much as Giotto pushed the late Gothic style toward the Renaissance with his abandonment of flat surfaces in favor of shaded, rounded bodies and a perspective, Masaccio is the one who is considered the first true Renaissance master, despite the fact that he only worked for a few years before passing away at the age of 27. Masaccio’s claim to glory in his incredibly short life are the frescoes he created in the Brancacci Chapel together with his mentor Masolino. Masaccio admirers from Vasari onward have pointed out the realism of his figures. These faces say something. They are no longer the frozen, solemn expressions of generic faces of medieval art. While an earlier image of Adam and Eve painted by Masolino offers a static, non-individualized portrait of the original sinners, Masaccio’s cast-out Adam and Eve from 1524 are real people full of anguish, shame, and remorse.

After Masaccio painted those images, there was no going back. The Renaissance’s focus on individual drama and true emotions entered art.

Another face of a Tuscan beauty was painted by Antonella da Messina about 50 years later than the characters in the Brancacci Chapel. His Madonna in St. John the Evangelist, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels is a real person, modeled by some young woman whose slightly pursed lips have such a human expression of worry.

Not all Renaissance faces are found in religious artworks. For example, Andrea della Robbia’s terracotta sculptures grace many places in Tuscany, one of the most visible being those endearing swaddled infants that decorate the Orphanage of the Innocents in central Florence.

The Bargello Museum houses a more intimate portrait by della Robbia in glazed clay. It is of a young woman with hair that swings in wispy pigtails, while her head leans forward. She has such a lifelike, contemporary expression—this is a portrait of a person rather than a decoration of a wall.

The most magnificent parade of Renaissance faces can be found at an old Medici palace in glorious, fairy-tale frescoes called The Calvalcade of the Magi painted by Tuscan artist Benozzo Gozzoli. The first grand Medici—Cosimo the Elder—had started the building of the main family residence in the center of Florence in 1447, but the palazzo and the chapel took years to construct; by the time Gozzoli was completing the chapel decoration in 1462, Cosimo was in decline. Since a new generation of Medicis had by then come to prominence, Gozzoli included them in this imaginary parade of the Three Kings. Gozzoli created a visual delight—a fantastic portrait gallery of various of his Medici patrons dressed as characters from the procession and surrounded by hunting scenes and scores of exotic animals.

Gozzoli’s Calvacade is a wildly colorful panorama of people dressed in sumptuous tunics, riding magnificent horses rendered in detail down to the smallest bulging vein. The three kings, dripping with adornments, are portraits of specific rulers. The Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg who represents the ruler of the West is portrayed as an old Magus. The middle-aged Magus is embodied by emperor John VIII Palaeologus as the Eastern ruler, and the youngest Magus is thought to be Gozzoli’s portrait of Lorenzo (not yet the Magnificent) Medici. All three are wearing wildly decorated crowns and riding white stallions.

Not all of Gozzoli’s expressive faces are human. Since the procession of the Magi is supposed to take place in the Middle East—mysterious yet unvisited by the painter—the cavalcade is populated with exotic animals: some camels, a morose-looking monkey on a silk cushion, a lot of birds, and deer. The best are the cheetahs. The whitish one looks like a cross between a dog and a mythical lion, and the other—the one with golden fur sitting on a horse—has a more cat-like appearance and stares intently forward.

The final Tuscan face comes from a much later period than the Renaissance. It is a portrait of a woman who, in the early 18th century, literally gave a princely gift to the people of her province. Visitors to Florence’s art-packed museums and churches are rarely aware that the city owes its concentration of beauty to this woman—the last of the Medicis.

In 1743, princess Anna Maria Louisa de’ Medici was 76 years old, having outlived both her husband, Elector Johann Wilhelm II, and her brother, Gian Gastone, Elector Palatine and the last of the Medicis. She is the woman responsible for the incredible trove of art that has survived in Florence until our day. Childless, Anna Maria willed the entire Medici family wealth—including the art legacy contained in the Uffizi Gallery, the Palazzo Pitti, and other Medici homes—to the people of Florence. Her will expressed it this way: “The Most Serene Electress cedes, bestows and transfers…galleries, paintings, statues, libraries, jewelry and other precious things…upon the express condition it be maintained as ornamentation of the State, for public use and to attract the curiosity of foreigners, nor shall it ever be removed or transported outside of the capital and the Grand Ducal State.”

If not for Anna Maria Louisa’s foresight, many Florentine paintings would have been sold off in the 18th and 19th centuries to English travelers and in the 20th century to American mega-collectors. The Princess’s legacy has ensured the city’s beauty and relevance for our generation, “foreigners” included.