Food for the Soul: Women Art Exhibitions—Venice and Paris

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

In recent years, exhibitions of women’s art have gained so much popularity that almost every week there is a local exhibition somewhere in the world. Predictably, the most ambitious shows tend to be hosted in the global art centers of Paris and Venice. Two important exhibitions focused on women artists are ongoing now at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and at Musée du Luxembourg in Paris.

The intimate Peggy Guggenheim Collection, one of my favorite museums, is based in Guggenheim’s “unfinished palazzo” in Venice. The museum has put on a deeply researched show entitled ”Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Reality.” Technically speaking, the Venice exhibition is devoted to Surrealists of both sexes—including male artists like Max Ernst (showcasing the star of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Ernst’s Attirement of the Bride, shown above), Giorgio de Chirico, Victor Brauner, Salvador Dalì, and Rene Magritte—but it is the curators’ assembly of rarely seen female Surrealist art that makes this exhibition so valuable. The exhibition focuses on Surrealism’s strong interest in magic and the occult—themes that have always attracted women’s attention and insights.

Before the 20th century, women artists often explored their inner worlds through intimate family portraits (such as those by Impressionists Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot) or even through abstract compositions (for example, by Hilma af Klint or Natalia Goncharova). The advent of Surrealism gave them a perfect tool to express female intuition, dreams, and fantasies; to unleash a repressed sexuality; or to pursue female-oriented interests (that is, more organic, less scientific) in nature or psychology. Surrealism removed the need for realism in subject or form, while bringing to the foreground the unsaid, the hidden, the grotesque, or the unusual. It is also the movement that elevated the position of female artists to a higher degree of respect and attention than any other previous “-isms” in art. Women’s ease in connecting with the subconscious and their frequent interest in poetry and magic turned out to be their ace card in creating exceptional art.

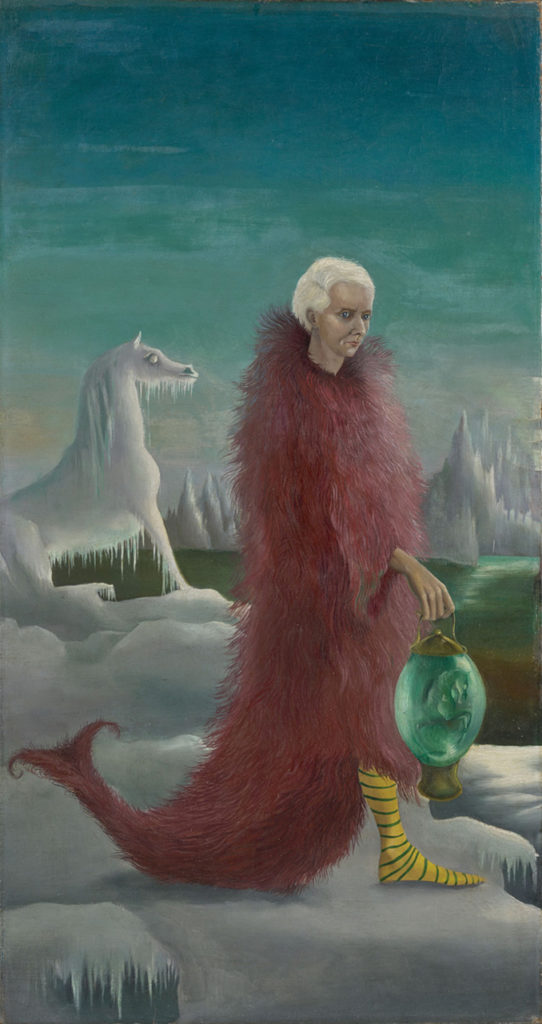

Leonor Fini (1907-1996) had too much of a strong personality to be a close follower of André Breton, the founder and a guru of the French Surrealist movement, but in the 1930s she was not only socially connected with the leaders of the movement (such as poet Paul Éluard, painter Max Ernst—with whom she had a brief affair—and artist Leonora Carrington, with whom she had a complicated friendship), but she also created many works expressing her fascinations and fantasies, including images of rotting vegetation and dark pools, works illustrating themes of death and magic, and fairy-tale-like portraits of women. Fini, a flamboyant woman of Italian-Argentinean-Spanish descent, was a passionate individual, and a woman very conscious of her struggle against male dominance, especially in the art world of her era. She would often paint portraits—of herself and other women—in a position of control and full of mysterious energy. The Portrait of Princess Francesca Ruspoli, presented at the Venice exhibition, is an example. It’s interesting that Fini, at the center of the artistic avant-garde in the 1930s and 1940s, was then largely absent from art history for many decades (most compendia of female artists simply do not list her) and is only now being recognized again.

Any artist who explores a world of fantasy or magic—or at least an alternate reality—has to create that whole world from scratch and populate it with entirely new creatures and scenes. This is perhaps why so many Surrealist canvases, from Dalí to Kurt Seligmann, are such arrays of symbols, fantastic elements, or personages, all placed in complicated, oneiric landscapes.

The Pleasures of Dagobert by Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) is an example of one such attempt to create a world of one’s own imagination. Carrington started out as an English artist, becoming a popular member of the Surrealist movement in Paris and a lover of Max Ernst, for whom he left his wife to share a bohemian lifestyle in Paris. The breakout of WWII changed all that. Ernst, as a German national, was interned; Carrington escaped across the channel. By the time they both ended up in exile in the U.S., their relationship was over, and Carrington spent the rest of her life in Mexico, having survived a psychotic episode and brutal medical treatment in England. Mexico and the new circle of friends she found there were her escape from war-torn Europe and from destructive relationships with Ernst and her own family. In Mexico, she would go on to create artworks devoted to magic, mythology, and cross-cultural imagery. The Pleasures of Dagobert, painted in her new country in 1945, created her own magic world; it reveals her departure from the overwhelming influence of Ernst on her life and art, while also making reference to French and English medieval art and history.

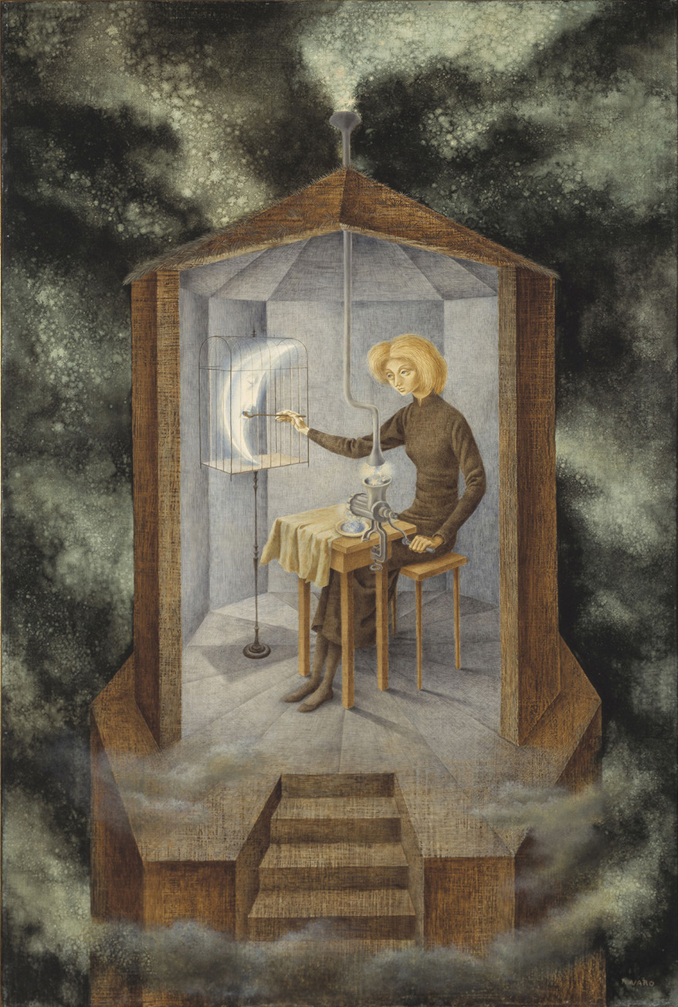

The exhibition displays several works of female artists whose art is as enchanting as it is rarely seen in museums, at least in the U.S. One of these women is Remedios Varo (1908-1963), a Spanish artist who also lived and created in Mexico. She was Carrington’s contemporary and her friend, and while her surrealist style is much different from Carrington’s, it, too, places women rather than men at the center of magical practice. Varo’s Celestial Pablum shows a woman (a magician?) who is grinding stardust into nourishment she feeds to a sickly-looking and caged moon. Pablum means “bland or trite entertainment,” so perhaps this is a metaphor for the daily humdrum of existence. There can be so many interpretations of this image that is both poetic and a bit nostalgic; all Varo’s paintings have numerous meanings and stories embedded in them.

In making magic and the occult its focus, the exhibition brings in examples of art from a wide range of female artists, from the tragic and under-recognized Leonora Carrington to the over-celebrated Frida Kahlo, as well as from underappreciated mid-century women artists like Kay Sage and Dorothea Tanning. These assembled works attest to the artists’ pioneering interest in women’s study of witchcraft, Wicca, and modern occultism (presaging the New Age’s fascination with modern magic). Theirs is a women-centered imagery, so different from the works of male Surrealists.

The exhibition, a joint effort between the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Museum Barberini, runs between April 9 and September 26, 2022.

As any reader of Hemingway would remember, 1920s Paris was an exciting place to be. Coming out of the brutal and protracted WWI, people all over Europe wanted to party—and artists wanted to explore modernity. Women, drafted en masse into men’s jobs during the war, were exploring the freedom to leave their housebound roles of wives, mothers, cooks, and domestic workers in favor of new jobs, artistic pursuits, male-style clothing, and sometimes a new sexual orientation.

The crucible of the ”jazz years” and Avant-Garde art (everything from Dadaism to Surrealism to Cubism) was in force in Paris. Women from many countries, and especially from the fallen Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, flocked to Paris to find themselves, artistically and socially. New female “archetypes” arose—the athlete in a tight costume, the garçonne (a woman with hair cut short and wearing men’s clothing, sometimes also gay but not necessarily), the bohemian intellectual, or the artist exploring new styles, from Abstract to Art Deco.

The current exhibition in Paris highlights those new female archetypes in artworks created mostly by immigrant artists from Eastern Europe, such as Tamara de Lempicka (originally Tamara Górska from a Polish family), Alexandra Bejcova (originally from Latvia), Stefania Łazarska (Polish), and Mela Muter (Polish-Jewish). Other artists featured in the exhibition include Suzanne Valadon (originally a muse of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, then an accomplished painter herself), French feminist artist Marie Laurencin, and Hungarian-Indian artist Amrita Sher-Gil. The art, created by self-emancipated, worldly women of multinational backgrounds, no longer sought to convey the subtle charms of Impressionism, or Victorian sweetness and feminine beauty. These female artists wanted to portray strong women in command of their bodies. In paintings of sportswomen, women in sexual encounters, or breastfeeding mothers, they painted women as themselves, rather than vehicles for picturesque studies of color and light.

Paintings like the one above, Young Woman, Head Backwards by Émilie Charmy (1878-1974), explore feminine ecstasy, so long denied and only seen before through the eyes of male artists. Paintings of maternity by Mela Muter (1876-1967) and Spanish Cubist Maria Blanchard (1881-1932) show the physicality of both mother and child—joyful but also quite honest about what a woman who has just given birth looks like.

The political and social emancipation of women in the early 20th century has been better documented than their artistic growth and liberation. The assemblage of so many female artworks at the exhibition fills in this historic gap by bringing attention to the many pionnières (female pioneers) who were busy creating art during the jazz years in Paris.

The exhibition, entitled Pionnières, is at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, between March 2 and July 10, 2022.