Food for the Soul: Global Trade in Art Part 3- Middle East

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

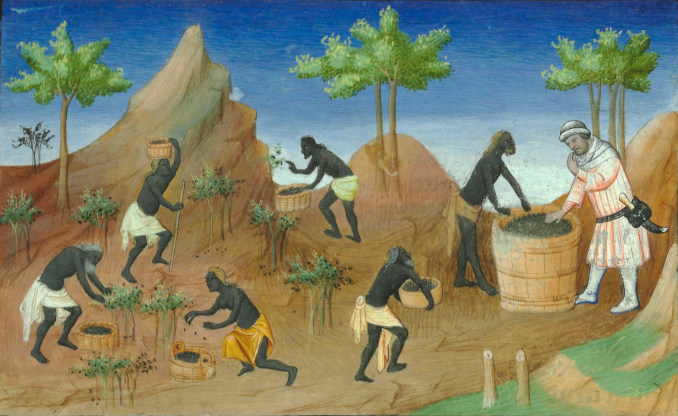

Even if Venice itself is not in the Middle East, until the early 1500s the Venetian empire, built on trade with Asia and the Levant, extended far beyond the city walls, incorporating such lands as Dalmatia and Istria, and reaching practically up to Constantinople. Venice was the gateway to the riches of the East—silk from China, spices and gemstones from India, Ceylon, and Indonesia, lapis and malachite from central Asia, carpets from Persia—all these goods flowed through Venice into Europe. In the late 1400s, for example, Venetian merchant galley ships would bring 400 tons of pepper from Egypt each year. This was a lot of wealth to spur the construction of palazzos, the importation of gold dishes, and the display of the finest fabrics in clothing.

In 1563, the Benedictine monks in Venice commissioned from Paolo Veronese a huge painting for their refectory. The artist delivered a 32-foot-long composition entitled The Marriage at Cana that included portraits of monarchs (François the 1st of France and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who fought against each other in several wars), noblemen, and his fellow artists (Tintoretto, Bassano, and Titian next to Veronese himself—all playing musical instruments). There are some 150 guests and servants at this fanciful wedding feast that is supposed to illustrate a Biblical scene—Jesus performing a miracle of changing water into wine—but the setting is a Venetian feast and the architecture is that of a Renaissance palazzo. Murano glass goblets, gold and silver dishes, and damask tablecloths decorate the tables at this Venetian-style banquet. However, this “who’s who” of the Venetian world could not omit the two most powerful figures from the Turkish empire: the sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (portrayed on the left, wearing a golden robe and seated between two ladies) and Sokollu Mehmet Pasha, the sultan’s Grand Vizier and the most powerful “prime minister” of the Ottoman Empire. Their presence in this painting attests to the importance of the constant interactions between the Venetians and both traders and rulers of the Turkish lands. The painting is famous for being the largest painting of a table in history, as well as an artwork plundered by Napoleon’s army in 1797 and never returned to Italy.

Painted around 1525, a canvas called Reception of a Venetian Delegation in Damascus in 1511 illustrated that the Venetian trade and political contacts went both ways. In a pre-photography world, such a painting feels almost like a “reportage“ on the Venetian notables visiting Syria. Somberly dressed Venetians are easy to spot among the colorful robes of their hosts, with the whole city bathed in the white sun of the Damascus plateau.

Naturally, being a gateway to the Orient, Venice would have been full of merchants and dignitaries from the Middle Eastern lands. Several works of late-Renaissance artists document well this melting pot of Italian and Middle Eastern people mingling on Venetian campos. Vittore Carpaccio painted St. Stephen, the first martyr of the early Christian church, preaching in the streets of Jerusalem. The city’s buildings look much more Italian than Middle Eastern (especially the octagonal church with a cupola), but there are also a few minarets, and the enthralled crowd consists of men in turbans and brocaded robes as well as women in pillbox-shaped hats that were standard in the 16th-century Ottoman empire. Carpaccio painted this work and four others for members of a Wool Guild (St. Stephen being their patron saint). Only three out of five of the canvases survived, and in all of them, the artist mixes Venetian and Middle Eastern attires and architectural elements to illustrate episodes from the deacon’s history of preaching in Jerusalem.

Giovanni Mansueti illustrated the life of St. Mark, patron saint of Venice, in a series of large works made in the first quarter of the 1500s. The one above presents the moment of the saint’s capture in Alexandria on orders of the sultan. The architecture of the Alexandria square is rendered in the style of the Italian Renaissance, but the people are supposed to be Egyptian, so they wear elaborate headgear and the robes of Muslim people.

Eventually, however, the focal point of Europe’s economy shifted away from the Mediterranean region and pivoted toward the Atlantic coast. Power and wealth were transferred from southern Europe toward countries that ruled the Atlantic traffic—England, Spain, Portugal, and the Low Countries. The trade hegemony enjoyed by the Italian coastal cities of Genoa, Venice, and Pisa had waned.

In the pre-Columbian world, precious spices—pepper, nutmeg, saffron, turmeric, cinnamon, and so on—would come from the regions of India and the Indonesian islands, finding their way into Europe through Central Asia and then the Middle East. The spice trade contributed to the growth and power of the Ottoman Empire and the nearest European ports in southern Italy. However, once alternative routes to India were found through the Atlantic, the Middle Eastern merchants had to find new products to trade. One of them was coffee, which became popular in the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century and, over the next few centuries, spread through Vienna (after the coffee beans had been captured during the 1653 Battle of Vienna), as well to France and England. By the 18th century, coffee houses throughout Europe had become incubators of new social and literary thinking and even hotbeds of many revolutions—but that is another story.

Harem Scene with Drinking Coffee—an oriental fantasy painted in the 18th century by court painter Johann Samuel Mock for his patron, Augustus II the Strong, king of Poland and Saxony—illustrates the popularity of both “Turkish” attire (especially for exotic portraiture and court balls and masquerades) and the new beverage, coffee. This is an example of a European vision of Ottoman culture, often provided by artists who had not really traveled to the Orient (Mock was born in Germany and died in Warsaw, spending his life in Poland as a court artist). Oriental themes became more and more popular in art, fashion, and literature.

The pull of the exotic “Orient,” a term that encompassed anything from Egypt to India but very often meant the Islamic lands of North Africa, got a huge boost with Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt and what is today Syria. The general and his 40,000-strong Army of the Orient landed in Alexandria. Alongside the military presence, there were hundreds of scientists, writers, and artists, all keen on exploring both the contemporary and ancient cultures of the region. While the military expedition took only two short years, the French influence in the region extended for well over a century and a half, feeding Talleyrand’s original vision of colonialism in Africa. The Napoleonic government published in 1809 a massive compilation—a 24-volume Description of Egypt—which popularized the region’s landscape, history, customs, and society. French archeological and linguistic discoveries also launched the new science of Egyptology, while artists turned their attention to depicting “exotic-looking” lands and peoples.

Later on, this ongoing fascination with the Middle East grew into a wider movement called Orientalism. It started in France with artists like Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, Delacroix, and Jean-Léon Gérôme—artists who missed out on Napoleon’s era but were still infused with his spirit of conquest and fascination with overseas exploration. Gérôme, who visited Egypt six times, built a large part of his career around oriental fantasies, for example painting noble warriors and scenes from harems that of course he could not visit but could visualize in seductive narratives. Orientalist art, fed by these artists’ masterpieces (including Ingres’ odalisques, Decamps’ Arab warriors, and Gérôme’s merchants), flourished throughout the 19th century. The list of “Orientalists“ eventually blossomed to include hundreds of artists from practically all European countries.

Not all the “Orientalists” actually traveled. For example, Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres never visited North Africa, but he used the Orient as a setting to paint his sinuous odalisques, while Antoine-Jean Gros painted Napoleon in the Plague House in Jaffa not having visited Palestine. This armchair approach became less common as the 19th century progressed—artists of all nationalities started traveling to the oriental region in search of picturesque subjects, especially as tourism developed. Victorian-era artist Charles Robertson traveled extensively all over the Middle East, capturing both landscapes and genre scenes. The one above is a typical “Orientalist” image of carpet trading in Egypt, bound to please the owners of large estates in England, who would have been the potential buyers of colorful and exotic scenes like Robertson’s as well as large oriental carpets. However, even the most beautiful carpets were not the thing that dramatically altered the position of the Middle East in global trade. At the dawn of the 20th century, it turned out that the most significant trade goods of the Middle East were not the caravan goods of spices, coffee, or lapis stones, but the black gold of crude oil.

Oil brought untold riches and untold misery to the entire Middle East. Before the discovery of oil (in 1908 in Persia and in 1938 in Saudi Arabia), the sandy dunes of the region were populated with nomadic tribes. They would have looked like this depiction in a canvas by German painter Eugen Bracht entitled Rest in the Syrian Desert:

Soon after, the deserts of North Africa became battlegrounds in the frenetic search for the black oil. Romantic visions of turbaned warriors crossing the desert on camels gave way to photo reportages.

The Middle East may have become one of the most crucial regions for global trade, but an oil field is not a very graceful subject for a decorative painting.