Feast for the Eyes

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

No one has ever rendered fruits more juicy or seafood more fresh than 17th-century painters in the Low Countries. Starting with late-Renaissance artists such as Pieter Aertsen and continuing for a century and half afterwards in the works of Dutch painters from Frans Snyders to Vermeer, this decorative tradition raised the painting of kitchen scenes and foodstuffs to the level of perfection.

Still Life with Fruit and Lobster is one of many fruit, seafood, and flower arrangements painted by one of the masters of the genre: Jan Davidsz. de Heem. If his success can be measured by the prices he commanded, he was certainly on top, since he was able to charge 2000 guilders for his flower garland portrait of young Wilhelm III — a price equivalent to twice the annual income of a successful painter at the time. The intent behind such lush portrayals of food may have been primarily decorative, but these works also contained religious and moral symbolism now largely lost on modern generations. For example, cherries represented the “fruit of paradise,” while mussels and lobster were allusions to resurrection, and grapes and corn were references to the Eucharist.

Simple Meals and Feasts

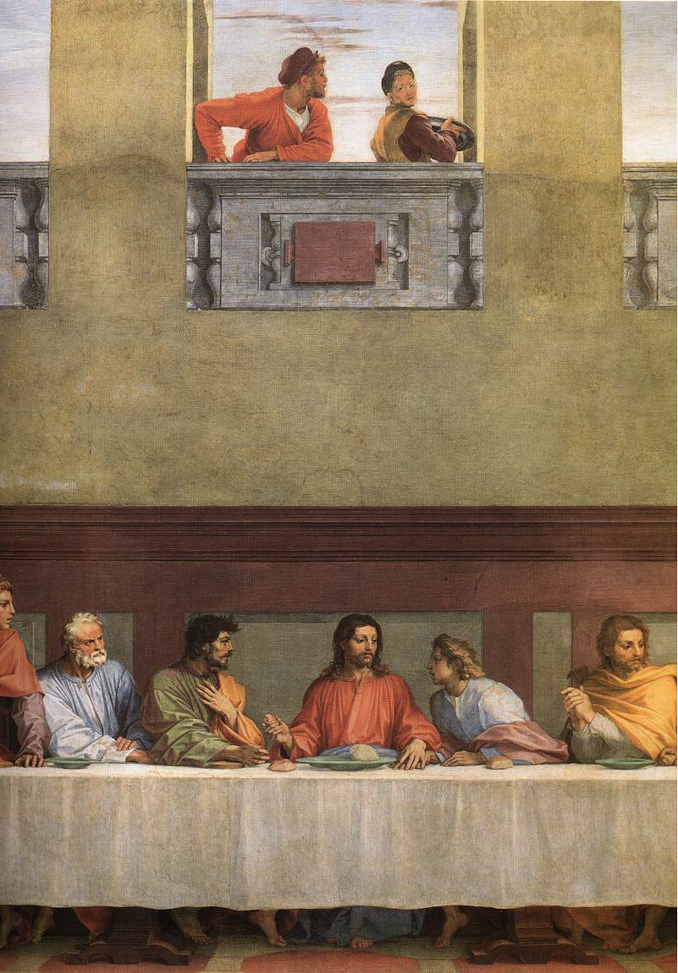

In art, the best examples of simple meals come from representations of Jesus’s life—either pictures of the “supper at Emmaus,” comprising only a few figures and a simple small table, or images of the Last Supper, where the only food required on the long table are some pieces of bread and, sometimes, chalices of wine.

You can usually find Italian cenacoli (paintings of the Last Supper) in refectories of monasteries. The most famous ones include da Vinci‘s fading fresco in Milan as well as Ghirlandaio’s cenacoli at the convent of San Marco and the Ognissanti church in Florence. However, one of the most picturesque representations is by Andrea del Sarto in the Florentine convent of San Michele. To increase the illusion of space, del Sarto painted a gallery from which two servants are witnessing the drama below. The artist meticulously prepared his fresco, making numerous sketches of hand gestures and faces of models for the varied expressions of the disciples surprised by Jesus’s prediction that one of them would betray him. Each saint has a different physiognomy and a different body language. Jesus endearingly places a calming palm on the hand of his disciple John, while the traitorous Judas makes an indignant gesture of false denial.

Whereas the tables in Last Supper paintings are devoid of any food except the bread that Jesus offers to “the one who will betray him,” scenes of feasts—biblical or allegorical—offered painters a chance to show off all kinds of foods and dishes. Allegories of the five senses (an Aristotelian theory popular as an art theme since the Middle Ages) offered painters a ready-made subject for this purpose.

The Senses of Hearing, Touch and Taste, painted by Jan Breughel the Elder in the early 17th century, is a painting of culinary abundance. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the central table (the woman’s red dress serves as an attention grabber), which is entirely covered with dishes of game and fruit platters. The woman is reaching for oysters, which symbolize refined taste as well as suggesting sensual pleasure. Servants to the right are bringing in more platters and wine chalices. At this type of aristocratic banquet, game trophies (a boar’s head, a pheasant, and a peacock) would have been more decorative than necessarily edible, pet animals would have been allowed to roam under the table, and there would have been musicians to entertain the diners.

In the Kitchen

The Dutch Baroque genre paintings – the first time when entire pictures were devoted to images of just food – were replete with symbolism, religious allusions and allegorical hints. In a picture commissioned by a wealthy patron, the artist would present beautifully painted food as a contemplative image—not just a wall adornment but also a reminder of religious or moral values. Flemish “kitchen scenes” would also sometimes have some allegorical messages in addition to their popularity as a decorative genre. Kitchens of an aristocratic household would have been as busy as a contemporary restaurant, with people roasting meat, preparing game, chopping firewood, baking bread, and grinding spices. All this busy and messy environment was perfect as a setting for an interesting picture.

If you compare Kitchen Scene painted by Teniers in in the 17th century with a 19th-century French realist painting, you can see the shift in how society perceived food. In 1899 Jehan Georges Vibert painted The Marvelous Sauce as a satire but certainly not as an allegory. By the 19th century depicting the preparation of food became a goal in itself with no religious or allegorical connotations. A messy castle kitchen shown in Flemish genre paintings gives way to a spotless room that celebrates haute cuisine.

The Marvelous Sauce is an image of a great French kitchen but it also is a particularly biting critique. Vibert was a multitalented man who was larger than life, being a prolific painter, writer, actor, satirist, and even a sharpshooter in the Franco-Prussian war. Above all, he was a popular realist painter. His numerous satirical pictures expressed a sentiment shared by many progressives in French society who were rebelling against the decadence and abuse of power and wealth by the clergy. Vibert’s anticlerical vignettes illustrated the over-comfortable life within the Catholic church—such as cardinals indulging in food, vicars reading immoral literature, or priests playing instruments.

Food can have restorative or healing properties—and sometimes, even an entire kitchen can have such an effect. German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner painted his Alpine Kitchen in 1918, when he was healing his addictions and psychological trauma from WWI during prolonged stays in the Swiss Alps. Kirchner’s pre-war art was much more dramatic, with aggressive lines and jagged edges, but he painted this picture with flat stripes of rosy and yellow shades. The simple wood-burning cabin stove creates a protective frame, and the person at the table (probably his companion Erna) seems to be drawing or perhaps making a lithograph; in any case, she is engaged in a positive, creative activity. This kitchen is a source of warmth and food but also a safe harbor from the ugliness and threat of the world far away from the mountains.

Vegetables and Fruit

Giuseppe Arcimboldi (his last name is often also spelled Arcimboldo) was a Milanese artist (he worked with his father on decorating the Milanese Duomo) whose talent attracted the attention of the emperor Maximilian I. In 1562, he was invited to the Habsburg court, where he painted conventional artwork and decorations for balls and masques. However, he gained fame for his “fantasies”—cleverly planned portraits composed of plants, foodstuffs, and even books or pieces of furniture. His Water is composed of fish, pearls, coral, and water mammals, his Librarian is an arrangement of books and paper, and his Waiter is a person made of kitchen pots, jugs, and barrels. The painting known as The Greengrocer is a composition of vegetables under a pot—if you upend the painting, you can see that they can all go into a large soup pot that, the other side up, serves as a hat. In fact, this painting, as well as The Cook (piglets on a plate) and A Basket of Fruit were painted as still-lifes, and it was only after reversing them that the viewer would discover that the foods created a portrait of a person.

Amusing as these “caprices” were, they were also made up of thoroughly researched and rendered objects from nature (including corn from the newly discovered Americas), and Arcimboldi was probably invested in the symbolism of these paintings as expressions of the universality of nature to which both the plants and people belonged. In short, while those vegetable puzzles, following the 16th-century taste for the “bizarre” in art, may have served to amuse the emperor and his court, they probably also expressed Arcimboldi’s humanist beliefs. Although his art subsequently fell into obscurity until the late 19th century, it went on to inspire the surrealists of the early 20th century. Today, his fanciful art jigsaws delight audiences in museums all over the world.

The 17th century was a golden age for the still-life genre. In both the Protestant Dutch Republic and the Catholic Spanish Netherlands, artists painted the most luscious and elaborate arrangements of food, plants, and dishes. In Spain, artists such as the young Velázquez would paint “kitchen scenes” called bodegónes, while in Italy, baskets overflowing with fruit decorated many religious or mythological scenes as well as serving as interior decorations for private homes and public buildings. Caravaggio painted Boy with a Basket of Fruit when he was freshly arrived in Rome from his native Lombardy and was working as a young member of the studio of the Mannerist artist Cavalier d’Arpino. This is Caravaggio’s first known still-life, but it is already full of his characteristic touches—distinct lighting created from a single if unseen source, his model a sensuous youth, and his naturalistic image of fruit so tempting you could imagine sinking your teeth into those ripe cherries and grapes. There is possibly some symbolism in this artwork—either referring to the tradition of Roman hospitality or the fullness of youth—but there is none of the elaborate religious code of similar Dutch works. Here, we can just enjoy the sensuality and freshness—both of the beautiful boy and the perfectly ripened fruit.

Once you have seen one of Cézanne’s paintings of fruit, you cannot unsee it—you will end up judging all other pictures of apples and pears against his ideas of color, composition, and brushwork. Thousands of apples have been painted copying Cezanne’s ideas, but his singular vision and brushwork make many subsequent apple pictures feel a bit derivative and less visually striking.

In 1928, Charles A. Loeser, an early and passionate collector of Cézanne’s works, bequeathed eight canvases to the “president of the United States for the adornment of the White House.” The exquisite small picture titled Still Life with Quince, Apples and Pears was among them. The bequest had a convoluted history, and the collection almost ended up at Washington’s National Gallery, but eventually this picture was placed in the private apartments of the presidential residence. As a result, it is much less known than other canvases by Cézanne found in major collections.

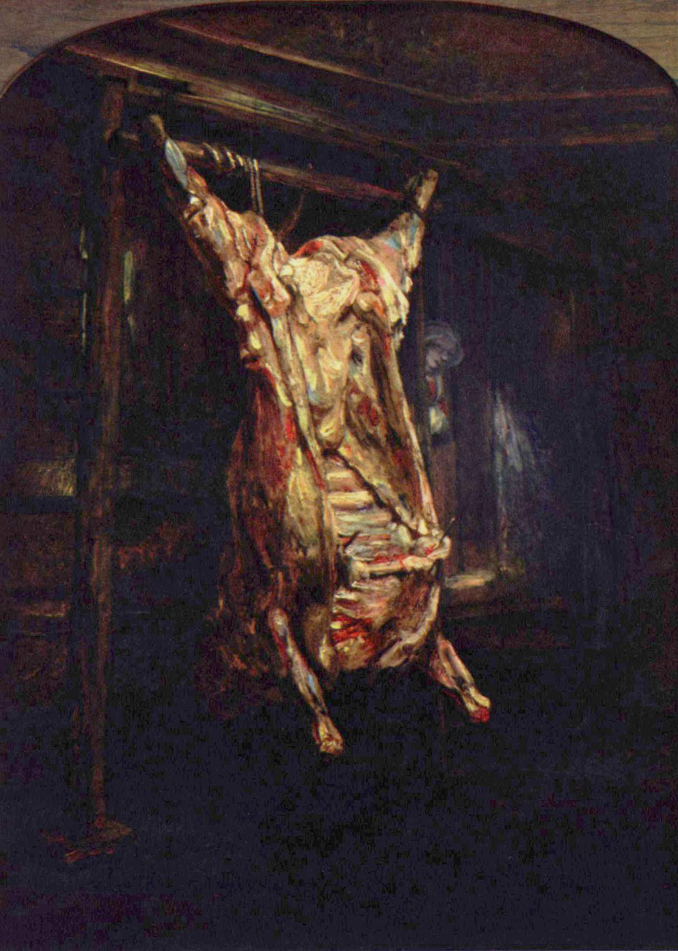

Masters Paint Meat

To contemporary eyes this brutal display of a carcass might be a shocking image, especially painted by the revered old master whose religious scenes and psychological portraits are so much better known. However, Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox can be regarded as both a religious and allegorical image, despite its unsparing realism. Beginning in the Middle Ages, pieces of meat had stood as symbols of Christ’s sacrifice in paintings of scenes from the New Testament. By the mid-17th century, when Rembrandt painted this picture, the image of a quartered body of beef could have been just a reminder of inevitable mortality or some other moral message, but it would still have had some symbolic meaning beyond the sheer naturalism of the butchery. The power of this harsh exposition of mutilated flesh has inspired many artists, most notably such somber 20th-century painters as Chaïm Soutine and Francis Bacon, both of whom were famous for their pessimistic imagery of torn flesh.

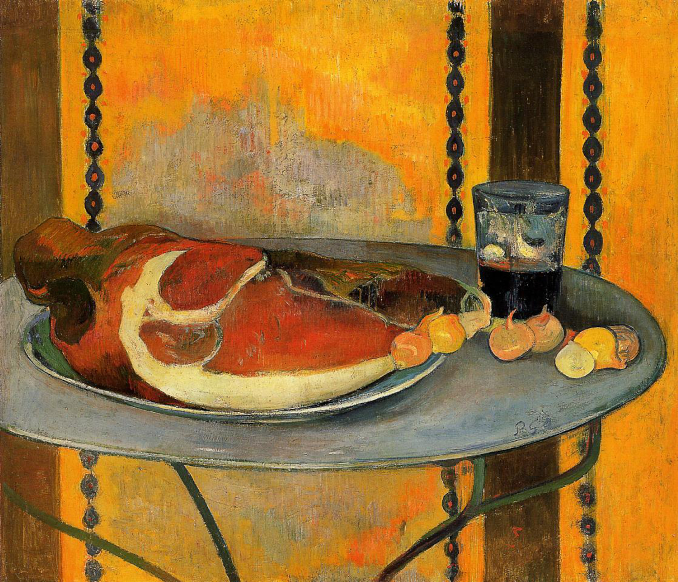

You can find Gauguin’s The Ham in one of my most favorite art galleries in the world—the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. Gauguin was enamored of Cézanne’s art, and his prized possession was a painting entitled Fruit Bowl, Glass and Apples. He referred to this work by Cézanne as “an exceptional pearl, the apple of my eye,” and he kept it for many years until desperately needed money for medical expenses forced him to sell it. (It is now in the Museum of Modern Art collection in New York.) By the time Gauguin painted The Ham in 1889, the religious symbolism of Baroque paintings of meat was mostly gone from art —instead, this is just an interesting composition of vivid colors and alternating round and vertical shapes. Gauguin evoked Cézanne’s style by painting the onions with a thick bluish outline and by placing the ham and the glass on a table that is off-center and slightly tilting. This followed Cézanne’s approach, which rejected traditional rules of perspective in favor of multiple points of view.

Desserts

Raphaelle Peale is considered the first and one of the most accomplished still-life painters in America. He was born in 1774 into an artistic family (his painter father named his other children Titian, Rembrandt, Sofonisba, Rubens, and Angelica Kauffmann—clearly, there were painterly expectations there). In his youth, he spent considerable time collecting specimens and doing taxidermy for his father’s natural history museum. This latter activity cost him his health; he was poisoned by arsenic and mercury in the specimens he handled. By age 35, he had started having deliriums and attacks of stomach pain that plagued him for the rest of his life. Peale specialized in small pictures, mostly of food, as evidenced by this precise and mouth-watering picture of iced cakes. This still-life is painted very much in style of the Flemish art of a century earlier, at a time when there were few domestic paintings of such quality in colonial America.

We do not know much about Clara Peeters, other than that she was born in Catholic Antwerp, lived in the Protestant Dutch Republic, and specialized in genre paintings of flower arrangements and richly appointed meal settings. Her paintings sometimes are symbolic meditations on the fleeting nature of life, replete with symbols of decay and passing. Many of them, however, are above all a celebration of earthly delights—food set out on tables full of fat cheese wheels and sugared snacks—all arranged on imported porcelain and among gadrooned silver ewers. She must have had rich patrons to have access to such costly props. In Still Life with Flowers, Goblet and Dainties, she placed all the trademarks of her pictures, including a bunch of botanically precise, full-bloomed flowers next to goblets with surfaces rendered in virtuoso realism—a wine glass, a gilt goblet, and a shiny water flagon. She even painted on the pewter surface a tiny reflection of herself, a “signature” trick featured in her other paintings as well. The dessert bowl is full of enticing sweets—dried figs and raisins with some other fruit candied in white sugar. Unfortunately, only a few dozen of the artist’s pictures have survived, and even if she was one of the precursors of the Dutch still-life genre that began with artists like her and exploded into thousands of still-life works over the next couple of centuries, Peeters herself remains almost unknown.

Meals with friends are not just about food, of course—they are also about friends getting together and the joy of talking to one another and sharing companionship while eating and drinking. Beyond basic sustenance, food plays numerous social and emotional roles in our lives, and this Luncheon of the Boating Party , so brilliantly conceived, staged, and painted by Renoir over several sittings, is the best expression of this idea. In fact, the food at this outdoor restaurant has already been cleared away, leaving just some wine and crumbs, yet the lively conversation goes on between people warmed up by the company and a good meal.

The Fournaise tavern pictured here—with two of the owner’s children, Alphonsine and Alphonse, Jr., perched on the terrace railing wearing hats—was a gathering place for a group of Renoir’s artistic friends. He planned this picture as carefully as the old masters would have composed their cenacoli, and with as many people as this tight arrangement would fit (there are 14 persons interacting here). The conversation is lively, and everyone is animated by the good meal they must have had. Even if Luncheon is a painting with little actual food visible, it is still a master painting about the pleasure of food.