Food for the Soul – The Lust for Travel

James Tissot. Ball on Shipboard (1874). Tate Britain. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.”

~ St. Augustine

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

While we may be upset by the various pandemic travel restrictions the world is now experiencing, it is worth keeping in mind that leisure travel, especially in large numbers, is a relatively new invention. It has only been around in Europe for about 300 years and, in other continents, for much less.

Peter Paul Rubens. Summer: Peasants Going to Market (c. 1618). The Royal Collection, UK. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If you lived in Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution, you would travel if you had some merchandise to sell or wanted to go on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela or another holy site. Or perhaps you traveled to go on a crusade or look for education or employment. If you were a noblewoman, you might have been married off to a faraway family. What you would not have done is travel for leisure. The roads were not safe—if there were any roads at all. Peasants would have been tied to their lord’s lands anyway, and even people who were not serfs would not have seen the point of braving swamps or dangerous forests to travel with no discernible purpose. Mass leisure travel was not yet an option.

Carl Spitzweg. English Tourists in the Campagna (1845). Alte Nationalgallerie, Berlin. Photo: Wikimedia Commmons

Things started to change in the 18th century. Roads and safety had improved, and the wealth and education of the upper classes had grown as well. Conquests of faraway continents fed the wanderlust of Europe’s young people, while economic pressures encouraged migration. Traveling for the sake of traveling first took off among young noblemen, and especially the English aristocrats for whom a year or two of visiting Italy or France was almost an obligatory step in their entrance to adulthood. Venice and Rome filled up with young foreigners sketching picturesque ruins and sowing their wild oats at the carnevale.

Bernardo Bellotto. View of the Grand Canal and Punta della Dogana (c. 1743). The Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Artists quickly moved in to fill the need for souvenirs. Part of the Grand Tour for a noble tourist would be to commission paintings while traveling—either views of Rome and Venice or a portrait executed by a fashionable and preferably fast artist. (The artists were mostly Italian, but some followed their customers from France or England.) Those trophies on canvas would be carried back to the traveler’s estates and presented to friends and family as a proof of the extensive tour. Venetian painters such as Canaletto, his nephew Bernardo Bellotto (who also signed his paintings as Bernardo Canaletto, so there are two artists of this name), and Francesco Guardi specialized in creating large and busy panoramas of the Grand Canal or St. Mark’s Square, expressly for foreign clients. They even sometimes painted capriccios, a genre of architectural fantasies. An artist would paint some picturesque but fictional Roman ruins or a palazzo set in nice countryside. Capriccios would not be representations of real places or historical buildings, but they would look sufficiently “Italian” and serve as perfect souvenirs.

Pompeo Batoni. Portrait of Francis Basset, 1st baron de Dunstanville and Basset (1778). The Prado. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One of the artists who made his living by painting suitably grand portraits of English nobility on Italian tours was Pompeo Batoni, the most prominent Italian portraitist of the second part of the 18th century. Batoni specialized in painting British nobles as well as European royalty. He painted about 175 portraits of English and Scottish aristocrats, often against picturesque antique props. The portrait above is that of Francis Basset, who toured Rome in 1777. The future baron of Dunstanville had Batoni paint him with the two landmarks of Castel Sant‘ Angelo and St. Peter’s Basilica in the background, leaning on an (invented) Roman pedestal. Batoni was a perfectionist, however, and did not finish the painting before his aristocratic client left Rome, so the painting was sent to England on board the frigate Westmoreland. Unfortunately, England, France, and Spain were waging a war for sea domination at the time. Despite the ship’s 26 cannons, the French seized it and subsequently sold it to the Spanish, together with its entire contents. The Westmoreland was packed to the gills with souvenirs—57 crates of valuable paintings, marble statues, jewels, candelabra, books, even religious relics—all the purchases and expensive knick-knacks shipped by the British aristocracy while roaming Europe. The baron of Dunstanville never got his tourist souvenir, and his portrait is now in the collection of the Prado National Museum in Madrid.

Eugène Louis Boudin. Bathing Time at Deauville (1865). National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sightseeing expanded to the middle classes in the early 19th century as the Industrial Revolution (first in England and then on the continent) ushered in the rapid construction of railroads, along with increased migration to cities characterized by crowded, unsanitary, and polluted living conditions. City dwellers now had the means—and a reason—to travel to the coast. By 1870 in Britain, there were about 13,500 miles of railroads that could get travelers not only to the main cities but also to the seaside resorts of St. Yves in Cornwall or Brighton south of London. In 1841, Thomas Cook founded his travel agency, initially escorting 500 people on an 11-mile railway journey but soon expanding to become the prime travel agency in the world.

Both English and French tourists started visiting the coast of Brittany, while vacationers from Central Europe would take the waters in Carlsbad or other fashionable spa resorts. By the end of the 19th century, millions of middle-class families were spending summers exploring seaside resorts and vacationing at quaint hotels.

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps. The Turkish Patrol (1831). The Wallace Collection, London, Photo: Wikimedia Commons

After Napoleon led his army into Egypt in 1798, Europe developed a fascination with North Africa and other “Oriental” places. Artists also began traveling to those regions, no longer content to simply imagine the exotic lands. The growth of leisure travel that expanded throughout the 19th century created a demand for anything “Oriental”: Persian carpets, Turkish brass pots, Venetian shawls, and genre paintings of “harems” and “Moroccan bazaars.” Collectors eagerly acquired works by lesser artists, while large canvases by masters such as Delacroix and Gérôme were admired at Paris exhibitions. In painting, Orientalism as a distinct genre was started by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, who launched it in 1831 by painting scenes from lands of the Ottoman empire. Decamps’ first major painting of an Oriental subject was a portrait of a police chief in Smyrna in 1828.

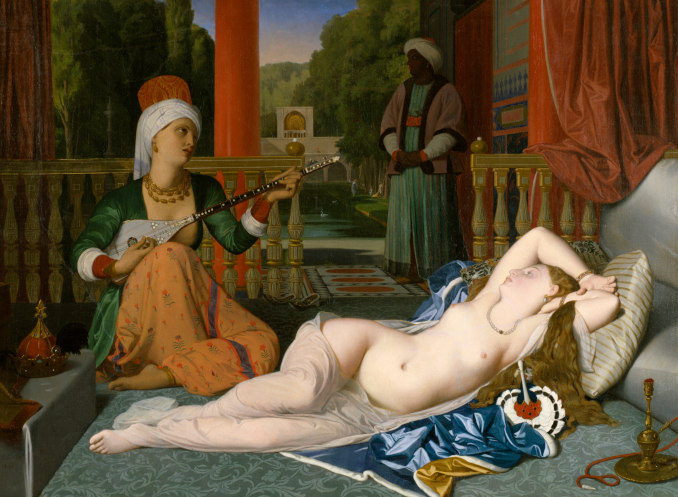

Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres (with assistance of Paul Flandrin). Odalisque with a Slave (1842). Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The genre became enormously popular in Europe, in part because it allowed the depiction of alluring nudes in the 19th-century era of prudish modesty, and in part because it brought a whiff of exotic adventure to people who could not actually get to Tangier, Cairo, or Istanbul—but who would read about these places in adventure novels or in their daily newspaper. The masterpiece in the category of exotic nudes, La Grande Baigneuse, was painted by Ingres in 1808. He actually painted several versions of the sinuous back of a sitting odalisque because of the constant demand for this image.

The Orientalism theme was woven throughout literature, opera, ballet, theater, and musical pieces for centuries, but in paintings, it reached its apogee toward the second part of the 19th century, when literally thousands of painters composed scenes from seraglios and Middle East battlefields or bazaars, real or imagined:

Jean-Léon Gérôme. The Carpet Merchant (c. 1887). Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Across the Atlantic, mass tourism started taking off in the mid-19th century, at least on the East Coast. In 1850, over 50,000 tourists annually visited Niagara Falls (out of a U.S. population of about 23 million). The site of this geological wonder was soon overrun by day trippers and visitors to hotels and viewing platforms, not to mention carnival attractions and souvenir stands. But if this first-ever American vacation destination was becoming more and more crowded and visually polluted, you could not have guessed it from the paintings of Frederic Edwin Church or Winslow Homer. Church immortalized the grandeur of the waterfall in his panoramic canvas Niagara, painted in 1857 and displayed at numerous shows, including the Exposition Universelle in Paris ten years later. Thanks to chromolithographs and other prints of the painting, marketed by the gallery that purchased the monumental work, the image became a symbol of the enormity and uniqueness of American landscapes. In creating this painting (and its “companion” Niagara Falls From the American Side in 1867), Church validated this location as one of the must-see travel wonders.

Frederic Edwin Church. Niagara (1857). National Gallery, Washington, DC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By 1881, Niagara Falls had crumbling rocks around the rim, hordes of day trippers were leaving trash, and factories and other buildings were obscuring the view. The deplorable state of this once-pristine nature view led upper-class visitors to avoid the site in favor of less-overrun places such as the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York. The scenery of this place inspired many writers and painters, prompting many of them to move into the Hudson Valley area, including Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, and Albert Bierstadt, who all contributed to the development of tourism in the area. While the majority of works created by artists visiting the Hudson Valley and later the Adirondacks were artistic landscapes, many of these artists also produced commercial illustrations for magazines or advertising for hotel and restaurant owners. For example, Winslow Homer created engravings with enticing, self-explanatory titles like Trapping in the Adirondacks and Deer-Stalking the Adirondacks in Winter. Some of them were designed for female tourists, like this Winslow Homer illustration for Appleton’s Journal in 1869.

Winslow Homer. The Beach at Long Branch, an engraving published as an Art Supplement to Appleton’s Journal (August 21, 1869). Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Jersey. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Homer, who was later celebrated as a prime American seascape artist, started much more modestly as an illustrator for magazines and other forms of advertising.

Winslow Homer. The Bridle Path, White Mountains (1868). Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

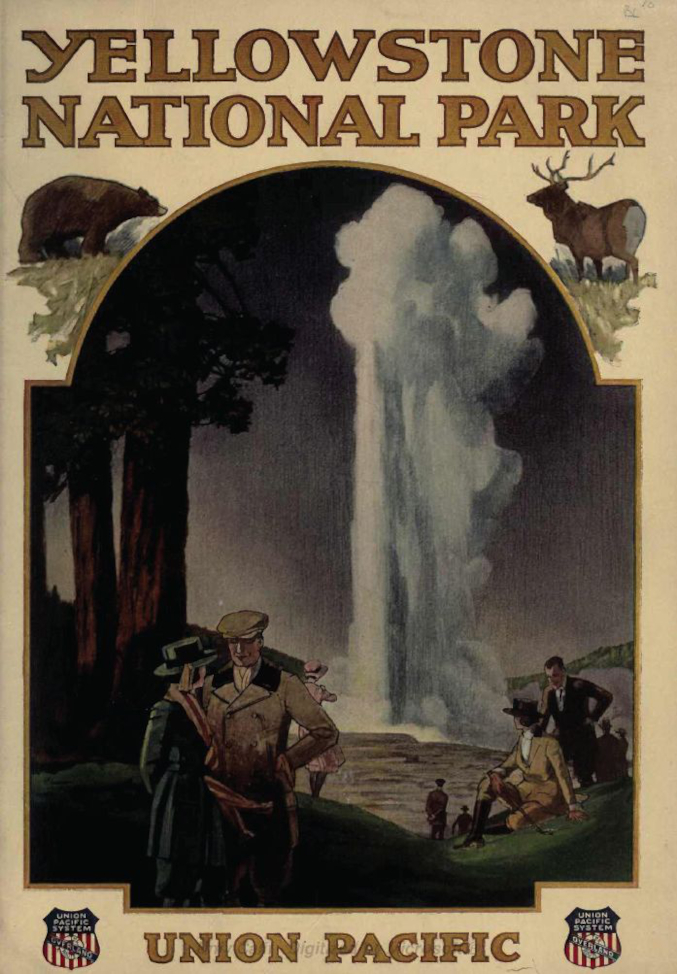

At the beginning of the 19th century, the American West was less accessible than the eastern part of the country, but by 1872, the first national park, Yellowstone, was created, ensuring that the western wilderness would avoid the fate of overdeveloped Niagara Falls.

Union Pacific Railroad brochure for Yellowstone National Park (1921). Photo: Mike Cline/Wikimedia Commons

One of the men who was instrumental in making Yellowstone a nature preserve was Thomas Moran. After he joined an expedition in 1871 to explore the Yellowstone lands, he documented over 30 locations that he then represented in oils and sketches. The beauty of these artworks helped persuade President Grant and the Congress to preserve Yellowstone as a national park. Moran devoted his life to portraying the unforgettable views of the canyons and waterfalls of Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Zion, and other wilderness locations in the American West. Already in Moran’s time, however, many of these mountain meadows and prairie plains had become inhabited and crisscrossed by railway tracks. His romanticized versions of dramatic orange rocks and stormy skies were his way of enhancing these places’ natural beauty, and his dramatic landscapes remain the most popular “portraits” of these vacation destinations to this day.

Thomas Moran. The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872). The Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While Winslow Homer was readily recognized as an outstanding landscape painter, praised especially for his sea views from the Maine coast, his contemporary John Singer Sargent had a harder time with art critics. Critics dismissed him as a “society painter,” sometimes accusing him of portraying people with a vacuous gaze (perhaps not realizing that the reason might be the vacuity of the models themselves rather than the artist’s lack of skill). But as much as Sargent might have been dismissed by critics, he was the most sought-after portraitist to the rich and famous during the Gilded Age. And in between his prestigious commissions (he painted aristocracy, famous writers, politicians, and more), he sketched and painted nature.

John Singer Sargent. Muddy Alligators (1917). Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sargent recorded his impressions of countless places around the world that he visited in his incessant travels. Born in Florence to a family of expats, Sargent had travel in his blood and his artwork; his freewheeling watercolors especially attest to his travels to the Middle East, all over Europe, and, in the U.S., in the American West as well Florida in the South and the Eastern Seaboard. Picturesque places would call to him in search of exotic subjects, the great outdoors, and warm sun. The charming Muddy Alligators with their sassy grins were painted in Florida. For New Yorkers, not to mention the Londoners who were Sargent’s principal clients, Florida’s alligators would have been as exotic as Egyptian camels.

The list of truly exotic places that Sargent sketched is very long. Many titles of his paintings attest to his wide roaming: Patio de los Leones in Alhambra, Hagia Sophia, Oranges at Corfu, Ilex Wood at Majorca, Bus Horses in Jerusalem, Egyptian Raising Water from the Nile, Tangier Street, and so many others. But he was capable of documenting the simple joys of camping as well, as evidenced in his series of watercolors painted when he was on wilderness camping trips.

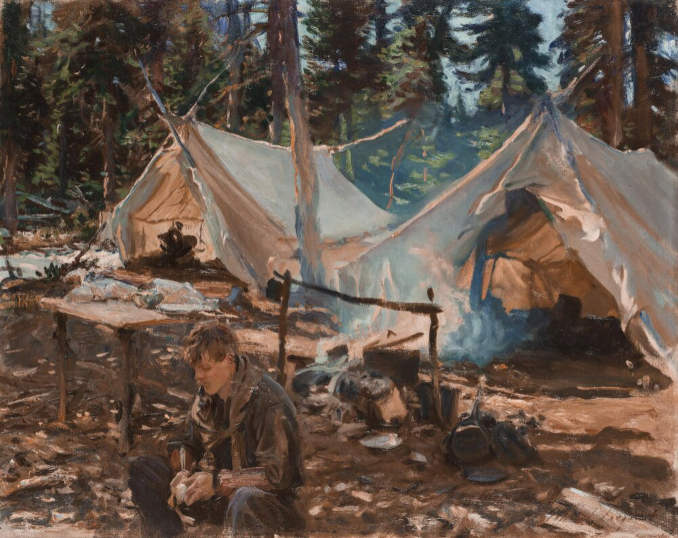

John Singer Sargent. Tents at Lake O’Hara (1916). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Here is one where he captured the simplicity and enjoyment of spending time at a campfire and in canvas tents. These are not amateurish vacation pictures either; they are painted by a master of color and light—striking and moody even in the modest medium of watercolor paint. The watercolors would sometimes be sketched more for private enjoyment than for any public display. He painted about 2000 of them throughout his life. Evan Charteris, his friend and biographer, said of these watercolors: “To live with Sargent’s water-colours is to live with sunshine captured and held.”

These days, mass vacation travel is part of everyday life, and it rarely gets recorded by serious painters. In a way, we have all become landscape artists with our digital cameras and access to remote locations. However, a beautiful landscape painting of a unique nature view can still feed our thirst for beauty and scratch that itch for travel.

Frederic Edwin Church. Tropical Landscape (1855). National Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Photo: Wikimedia Commons