Food for the Soul: Peeking into the Artist’s Mind — An Interview with Henryk Waniek

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

Even though most of the artists I admire are from the 20th century—from David Hockney to Leonora Carrington, and from Gerhard Richter to Francis Bacon—I’m usually not able to post about them here because images of their art are still under copyright. It is, therefore, a rare treat for me that I can write about a contemporary artist and especially one who I have admired for decades. This time, I have the artist’s permission to use images of his paintings.

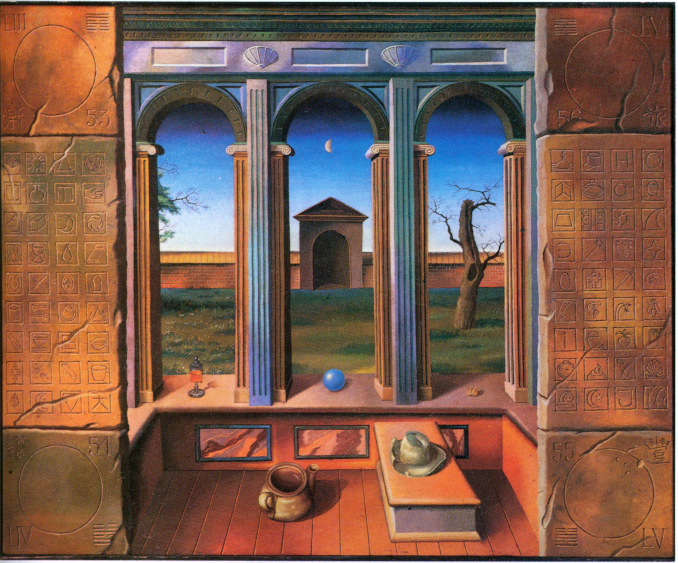

Henryk Waniek is an eminent Polish artist whose art is exhibited in museums and art galleries all over the world. Many decades ago, I discovered his art by accident. I was working on a movie where a scene was taking place in an art gallery. The director asked Waniek to lend his paintings for one day of filming to stage this scene. So, suddenly, I spent a day surrounded by Waniek’s paintings—colorful, surrealist, beautifully rendered images of dreams and imaginary lands. It was an array of brilliant canvases that looked as if Caspar David Friedrich was meeting Salvador Dalí. I was seduced by this art for life. The artist and I became lifelong friends, which is why today I have the luxury of being able to ask him questions and to publish photos of his paintings. Many of his artworks are now dispersed in private collections and can only be seen through this private documentation of the artist himself.

I have always been fascinated by how painters think—something that is impossible to figure out when you look at artworks, no matter how much analyzed, by an artist who is no longer alive. But Waniek is available, and he is also a published author of many books. He is a man very much interested in philosophy, esoterica, and history, and he is as good at juggling words as making colors dance on his canvases. So, I asked Waniek a few questions about his process as an artist. Here is a peek into how an artist thinks, accompanied by some examples of his stunning art.

What is your earliest memory of wanting to paint professionally?

Since childhood I have lived in the world of images—real and imagined. Like all children, I would draw and paint a lot. I was lucky to be exposed to drawings of Wilhelm Busch (German artist of the Victorian era). I still admire him. But I think I was particularly affected by the world of words—fables, children’s poems, and eventually more complex works like The Adventures of Pinocchio or The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen. I was less than four years old when I learned to read and write—all by myself. Painting became a choice for me much later, when I started seeking things as a teenager. Even then I was still not thinking of actually becoming a painter. I chose an art high school because I was persuaded by a friend. Then he dropped out, but I didn’t. It still did not feel like a conscious decision at that time—there were many options, and painting was just one of them.

Did any of your teachers or mentors ever try to steer you toward any particular painting genre or style?

You have to be very lucky to find a real teacher. I did get lucky at the Fine Arts Academy. I had a few discouraging experiences. Finally, I talked my way into the class of a professor, named Zbigniew Kowalewski, who was not very respected by his students. I said something disrespectful, too, and for three years this professor never said a word to me, but I knew that he sometimes would surreptitiously check out my work. At the time, I loved El Greco, and you could see that in my student work. And then I would find on my school desk some high-quality prints and albums about the works of this Spanish-Greek master. One day I found a collection of essays by Aldous Huxley called Music at Night, a book which was published in Poland before WWII. It contained an essay called “Jonah,” which was a wonderful introduction to the world of El Greco.

Sometimes I would find on my desk some paint tubes—in those times, they were hard to obtain. There were so many instances of these discreet interventions. My teacher wouldn’t do anything direct; he just looked (at what I was doing) and then he would unobtrusively help. I did not know his paintings because he was discreet about his own work. I saw them for the first time in the 1980s when I was already a recognized artist. And I am glad that it happened so late because they were very seductive. If I knew them as a student, I might have become a follower of Zbigniew Kowalewski. Many years later, we became good friends.

You are also a writer who has had many books published. Most painters do not have a second career as a writer, but you do. What is the relationship between your painting and your writing?

I know many good painters who express themselves with words as well as images. Usually, it is poetry but sometimes it is prose as well. I also know a lot of poets and writers who have the need to paint or draw. Curiously, this happens quite often. There are things that can be painted but not described. There are also things impossible to paint but which can be expressed with words. Western culture for centuries would have this interplay of images and literature. The experiences of both domains are priceless. Literature adds to a picture time that is not available otherwise. A picture adds to literature space that is otherwise not available. It is important to join those two dimensions, and for as long as I can remember I felt that these two ways of experiencing things are one. When I was a student, they were always trying to put visual art and writing in opposing camps. Abstractionism dominated in this period, which has left us with a lot of empty paint smears.

What world do you paint? Where does your inspiration come from?

Generally speaking, I am inspired by nature in the widest sense, not just as wild flora and fauna. Senses and a perception of the world are also part of nature, as well as tools and mediums that a painter uses. The nature of pigments—how fascinating is this! The world in my paintings does not have just one meaning; neither do dreams. In any case, a finished painting is only partially the product of its creator. Sometimes my own paintings are a mystery to me—a mystery that I sometimes cannot penetrate, even if I find it interesting. This is because my paintings, at least the ones I consider good, do not present a banal and boring reality. I believe that the world presented in a painting should not be what we see through a window or on a TV screen. A painting should reflect not the outside reality but our inside.

Who are your favorite artists, and why?

There aren’t too many of them, and it would be easier to name my favorite artworks rather than artists. There are a few like Alfred Kubin, Bosch, Magritte, and Ernst (in no particular order), but I’m the closest to the modest and hard-working Caspar David Friedrich. He was an early 19th-century painter, an artist who was spiritual but not excessively, and he was artistically somewhere between Romanticism and Classicism. I have many reasons to be fascinated by him, but especially because of his landscapes, which are not very realistic. I consider landscapes to be the noblest genre. I believe that the holy mission of paintings is to represent space and its properties.

Pure surrealism is now over 100 years old. Do you think it still can serve as a means of expression?

I do not consider surrealism much of a style—it did not create any clear artistic principles. Surrealism was more of an appeal for spiritual freedom, and that appeal resulted in so many different things. André Breton, the patriarch of this movement, ended up immersed in the occult and magic, which actually I’m interested in. After decades of revolutionary activities, Breton discovered that the source of lasting symbols, dreams, and desires lies in a human being. I’m sure this was a discovery with a long tradition and very useful for artists, even if the historic label of one more “-ism” does not serve any purpose. Especially now, when the world is full of people who would have been described in the 20th century as “surrealists” of some sort.

What spurs you to start painting a new picture? An image? A dream? A commission or an upcoming exhibition?

It’s hard to tell. Triggers can vary. The mind is always open and when you add a desire to express every thought inside, then the internal pressure results in an image. A dream often helps to formulate an image. When there are commercial reasons behind the work’s creation, as happens so often in the contemporary art market, then there is much less of inspiration to go around. Artists do yield to those considerations sometimes, but one has to be careful.

Regarding exhibitions—unless they are some important retrospectives—they are mostly meaningless rituals of the art market and they have little cultural value. I do not care for exhibitions much. I much prefer when someone pays attention to just one of my paintings. It is interesting that I must have seen thousands of paintings in my life, but the ones that I have really “seen” can be counted on one hand.

Do you have any favorite painting of yours or imagery in your art that you come back to all the time?

Many times, after I would part from one of my paintings that I considered a good one, I would paint a copy or a similar painting. This is actually good training for an artist—making a copy of one’s work, which often is coupled with corrections of some faults. But these are examples from more commercial activity.

Sometimes I would select some theme or motive to study the subject more. In the 1970s, I was interested in the architecture of the Italian Renaissance. There was a period when I forced myself to paint just in black and white. I did a dozen paintings entitled ”The Solomon’s Temple” because I got seduced by the beauty of this legend which has such a strong literary tradition. There was a time I only painted still lifes when I felt strongly about iconoclasm.

There was a moment when I publicly declared I would not paint anymore, and soon after I lost sight for several months. The miracle of medicine brought my eyesight back. I was curious what I would paint after having lost sight for a while, so for three to four years I did a lot of painting. But I did not want to get carried away, so I decided to put some limitations on myself and I called this cycle “Squaring a Circle.“ This is a paradox from antiquity, and I wanted to juxtapose the precision of geometry with the exuberance of nature. I was happy with the result, so at the moment I’m done with painting. I’d rather concentrate on writing now.

How do you start a painting? Do you have a precise image in your mind, or do you build it while painting? Do you do preparatory drawings?

At the end of the day, painting is a fascinating adventure and sometimes it’s better not to know how this is all going end up. Mistakes or outright failures can always be corrected. Or at least this is how it is when a painter is in front of his own painting. Sometimes a painter is part of some more public activity, and then he cannot afford to make a mistake. I have not had many such public moments, and I definitely prefer to surf alone on the waves of different moods. In a way, I paint my paintings for myself, and I am surprised when they turn out to be meaningful to other people. The process of painting has something of casting a letter in a bottle from a deserted island. In the end, the letters arrive somewhere and their arrival results in various reactions. I could tell you many stories about the peregrinations of my paintings, and sometimes they are quite incredible.

You have been painting for a long time. How has the approach to the art of painting changed over those few decades? I do not mean styles (e.g., hyperrealism or pop art), but the philosophy or the place of painting in culture or society.

Yes of course, everything changes with time. I’m no longer the frustrated freshman I was 60 years ago, and I have my set ways. This is why I am painting much less these days. I already know what I can do and what illusions I should abandon. I am not much affected by grand careers of painters, either those I know personally or those I don’t. I am aware that in our times a painting in a traditional sense is a bit of an anachronism. We are overwhelmed by paintings and pictures that have been created for commercial and informational purposes, many of them digital. There is nothing that can be done about it. The art of painting according to old-fashioned principles has become an elite and specialized activity. Its place in mass culture is that of an exception. And yet, for culture, since it does not like uniformity, exceptions are the most important.

Imagine that you are 20 again. Would you choose to become a painter again? Would you do something completely different?

Indeed, I was about 20 years old when I finally decided that for me, painting is the way to live. Eventually, I made every effort to become a painter. However, before I got to this point, I would do many other things. I would write, of course, but I was also a miner, a cinema manager, and a teacher. A “painter” or a ”writer” are not really “serious” professions. To be a writer or to be a painter simply means that you have some freedom. I feel that I succeeded in life and in that freedom, but not many people know that I feel that way. Maybe there are just a few people.…

Interview Copyright: Nina Heyn, February 28, 2023