Nina’s Blog 2023: Stones of Florence

Commesso mosaic from the workshop of Scarpelli Mosaici, Florence. Photo: Nina Heyn

Like all of Italy, except a bit more so, Florence is all about stone. Green and white marble bricks cover the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (popularly called the Duomo) to breathtaking effect.

Carved lions guard steps of palazzos and gardens, statues of saints decorate outside walls of churches, and stone lintels, bricks, and columns support every building. Florence attracts millions wanting to see marvels in Carrara marble like Michelangelo’s statue of David and architectural triumphs in grey serena sandstone like the Pazzi Chapel.

The world-famous Carrara marble quarry has been in operation for two millennia. Michelangelo once spent eight months in Carrara selecting stones for sculptures that were planned by the pope in Rome.

Carrara is less than two hours’ drive from Florence, and if you travel toward the coast to visit Pisa or Genoa, you can spot marble wholesalers’ yards in the countryside.

Stone is everywhere in Tuscany. In Florence, granite lintels line street curbs and doorways and, as any tourist who has visited Florence in the summer would attest, streets are paved with hard and very hot cobbles everywhere. And then there are the smallest stones—the semi-precious ones, such as malachite, lapis, jasper, carnelian, and onyx. The Florentine art of arranging colorful stones into mosaic pictures is called commesso.

The Italian art of meticulous color selection, polishing and arranging semi-precious stones into pictures, is an old one. Stone artworks, from agate cameos to statuettes and mosaics, were popular in ancient Greece and Rome, but these arts lapsed, together with many others, until the Renaissance. In the 1500s, not only did refined collectors start searching for stone artworks from antiquity, but also the old arts of stone grinding and arrangement were revived. The patronage of the Medici Duke Francesco I (1541-1587) resulted in the setting up of the first Florentine stone workshop, which provided decorations for the Medici court. Soon, the ducal workshop would also provide artworks for various European courts.

Opificio delle Pietre Dure (literally “workshop of semi-precious stones”) started out as the ducal workshop in the 16th century, and it still exists today as a small museum often ignored by foreign tourists. It displays historical stone works by designers and artisans from the 17th through the 19th centuries. The best examples of this art are showcased at grand Florentine museums—Palazzo Vecchio, L’Uffizi, and Palazzo Pitti—but this small museum explains the process of making the mosaics that have been a Florentine trademark for several centuries. Opificio also has a second, important function as a national center of art restoration, based in several modern laboratories and research facilities.

A commesso mosaic starts with a painting. An artist would first paint on canvas a picture, which would then serve as a model for the stone mosaic executed by stone-cutters.

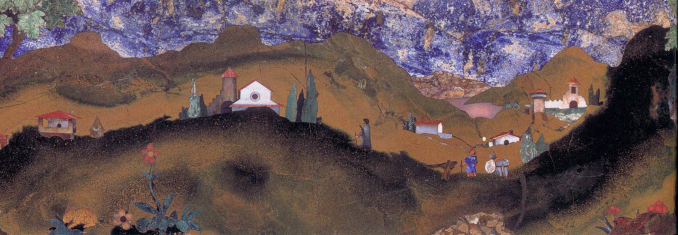

Here is an example of such a painting from 1752 which was rendered in stone a few decades later around 1776. Giuseppe Zocchi was an 18th-century artist in Florence who created many design paintings (called “models”) for stone workshops to adapt into mosaics. The one above comes from a series of scenes called The Arts. Below is the same picture detail, this time rendered in semi-precious stones, especially the bright lapis lazuli and yellow jasper.

The techniques to create a Florentine mosaic have not changed for centuries. Once the stones were sourced (for example, with lapis from Afghanistan, jasper from Sicily, and granite from Siberia) and color-matched, they would be cut into shapes with a steel wire strung on a bow.

They would then be polished with corundum paste, cut into precise slivers, assembled into designs, and polished again. It is a very exacting and labor-intensive process. Even if this craft is now rare, in Florence there are artisanal workshops where you can still witness the ancient technique and acquire treasures for your own collection.

I found a revived old workshop in the city center. Scarpelli Mosaici is a family company that manufactures and sells completed commesso pictures (usually traditional landscapes and flower compositions), but they also accept commissions for made-to-order images (apparently, one of the most common requests comes from American customers who want to commemorate their dogs). The fun is to watch the company’s artisans create commesso compositions, using the same bow technique as was done for centuries.

Working with stone in Florence is an art that is very much alive.