Food for the Soul: Animal Hunt at Art Institute of Chicago

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Comprehensive and large-scope art museums tend to be those created in centuries past, such as the Louvre in the 18th century and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”) in the 19th century. Their function was to provide the inhabitants of big cities with collections that were educational, displaying fine art but also historical artifacts and, sometimes, stuffed exotic animals (think Smithsonian), collections of old weapons, medieval manuscripts, or early photography.

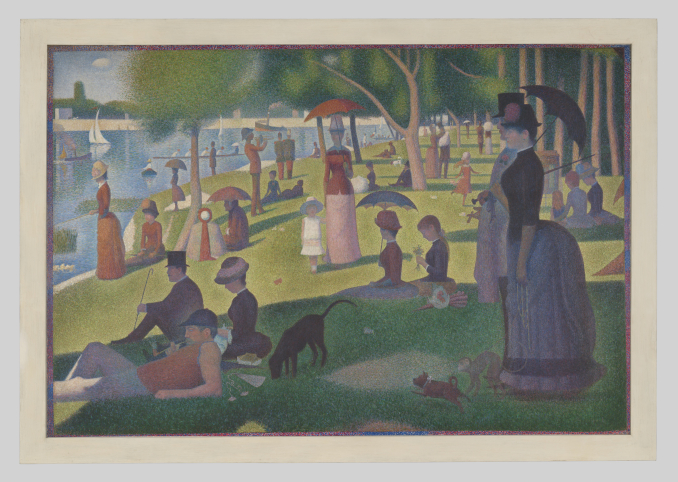

The Art Institute of Chicago houses one such encyclopedic collection. Established in 1879 as a cultural focus of the growing city, it has expanded from original few rented rooms to the classical structure built for Chicago’s World Fair in 1893, with its latest addition being a modern art wing designed by Renzo Piano in 2009. It is now the second largest museum in the U.S. (after the Met), and it showcases famous paintings such as Paris Street; Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte and Georges Seurat’s iconic A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884. The museum also has beautifully displayed sections of non-Western art, an antiquity department, photography, and areas devoted to architectural design, textiles, and decorative art. A full day in the museum would not be enough to take in all its treasures.

I tried to see as much as I could during a recent visit. During my long walks through the halls, I was struck by how few children I saw. Thanks to its vibrant college scene, Chicago has plenty of twenty-year-olds to fill the visitors’ lines, but I did not spot many school-age kids. And it is a pity, because the museum halls could offer a veritable treasure hunt for kids—for example, by looking for various creatures in the museum’s collection.

So … here is a virtual walk through the halls of Chicago’s Art Institute, where I try to spot some unusual animals from its collection of over 300,000 artworks placed in various galleries throughout the museum.

In 1875, the family of Winslow Homer started vacationing in Prout’s Neck, an up-and-coming seaside area in the southern part of Maine. Soon after, Homer’s younger brother and especially their father started investing heavily in the area, buying up all available lots for further sales and subdivisions. Those wise land investments secured the family’s affluence and allowed Winslow to live there comfortably for years. The artist spent many years making commercial illustrations for travel companies, women’s magazines, and advertising as well creating conventional landscapes for sale at galleries. Once he settled at Prout’s Neck and no longer had to work for a living, his art changed, too. He became interested in unusual seascapes, and he developed a dramatic diagonal composition to enhance the narrative. The Herring Net comes from that period in Homer’s art—we see a dory boat at an angle, and two men struggling with the net, weighted with fish, hanging at a diagonal while the heavy swell of waves adds movement to the scene. For 21st-century viewers, this image of daily work at sea is also a window into times past—these days, very few fish are caught by just a couple of fishermen with a small net.

After many years of attempts, in 1709 a German alchemist named Johann Fredrich Böttger (or perhaps his boss, who died a few years earlier) finally broke the Chinese secret of making hard-paste porcelain by successfully combining an appropriate local clay with the right ingredients and developing the firing process. This allowed porcelain locally produced in the city of Meissen to rival porcelain objects imported from China. The 18th century could not get enough of porcelain products—ranging from dishes to decorative clocks, vases, or ornaments—so the discovery of the secret of making porcelain that was both durable and white was tantamount to the discovery of gold.

Augustus II the Strong, king of Poland and Saxony, was an über-collector of art. He already had a massive collection of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, but once the local porcelain produced in Meissen became available, he rushed to place huge orders. In 1728, he had an idea for a royal menagerie of animals—all made of porcelain—for his Japanese Palace in Dresden. A sculptor named Johann Joachim Kändler was hired to create models of dozens of animals. His sculptures not only were showpieces of artistry, capturing animals’ lifelike poses and characteristics, but were also achievements of technology. Firing such large clay figures without cracks was a challenge in itself, and having the colorants survive high temperatures was even more so. Kändler’s King Vulture is, therefore, a double masterpiece of successful porcelain firing and coloring, achieved at the Meissen factory that was barely twenty years old at the time. Some of Kändler’s creatures were never even painted, as evidenced by a turkey sculpture from the same collection (now at the Getty Center in Los Angeles).

A Monumental Portrait of a Monkey comes from the state of Rajasthan in India. The artist’s name is unknown. Historians have dubbed him a “Master of Stippling” because he is known for about four dozen other paintings in which he pioneered a new style of Mughal Empire art. This monkey is clearly a pet, kept on a silken cord. It has an almost human face and hands, so this is not a naturalistic portrait of an animal but perhaps a subtle allegory of a courtier—or it may simply be an amusing animal picture. In Indian art, it was rare for monkeys to be subjects of stand-alone, large pictures (unless it was a picture of the god Hanuman, but he would be clearly shown as a god and not an animal), so this is an unusual but definitely charming picture.

Wassily Kandinsky created Painting with Troika, a picture of a peasant cart being pulled by galloping horses across a madly colored countryside, when he was on the cusp of his transition from figurative art to the Abstractionism that he pioneered. In his earlier works, he explored “modern art” with bold colors and lines while still making references to actual objects and actions—like these rushing Russian horses (a troika was a traditional arrangement of horses all abreast, pulling a sled or cart). Eventually, Kandinsky’s paintings became arrangements of colors and lines deliberately voided of any narrative, so that they would, in his words in 1912, become “vibrations of the soul.” But we are lucky that not all of his artworks were so abstract—this one, full of movement and intriguing shapes (the horses are marked by white ovals and the people are yellow rhomboids), is a delight.

The Chicago Art Institute houses two ceramic sculptures that would delight any kid who likes fantastical creatures. One of them is called Pelican, but her wings are more like those of a dragon, and she looks a bit like a Notre Dame gargoyle (“she” because she has mammal breasts on her chest). The second animal is called Bull, but he, too, sports wings, while sitting like a dog and looking with great interest at a tiny red snail. These charming creatures were created by artist Emmanuel Frémiet, who spent most of his professional life making statues of heroes for public squares; he originally designed these two as neo-Gothic decorations for a palace. These cat-sized sculptures in bright turquoise and copper colors are small ceramic versions of the original stone statues.

Frémiet was a French sculptor who spent some time doing scientific paintings at morgues as well as executing various commissions for statues and fountains, including one of Joan of Arc in Paris. His greatest fondness must have been for animals, however, because he specialized in making figurines, big and small, of various animals. In 19th c. artists skilled in creating realistic images and sculptures were called animaliers. Frémiet was such an animalier. He started exhibiting animal sculptures in 1843, when he was barely 19 years old, and he continued drawing and sculpting them for decades thereafter, especially when he became a professor of drawing at the Parisian Jardin des Plantes, a botanical and zoological park in Paris. One sculpture that is familiar to many people is his bronze of a trapped young elephant, one of the three large statues that grace the front of the Musée d’Orsay.

Even today, metal figurines of Asian dragons, snakes, birds, butterflies, fish, or crayfish are often made of many small parts that can move when the figurine is handled. This iron “articulated dragon” was made in the last quarter of the 19th century by one of the most venerated metalsmith companies of Japan, the Myochin family, whose earliest signed craftworks date back to 1713. Their suits of armor were legendary; they also produced many jizai okimono (ornamental figures), even more so when Japan opened to the West and started exporting to Europe and the U.S. This particular dragon not only has beautifully rendered scales and spikes, but he also has such an endearing startled look, as if he were a plain garden lizard surprised on a path.

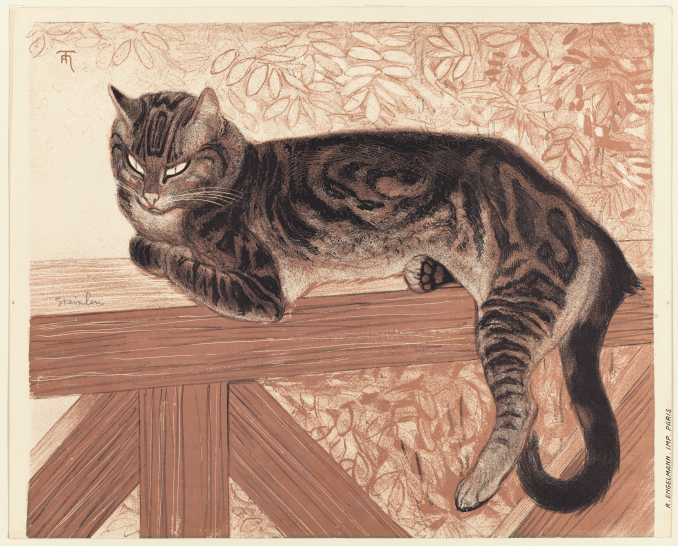

The opening of Japan to the West in 1868 was culturally a two-way street. Japan adopted Western clothing, a parliamentary system, and technology; the West, in turn, became fascinated with Japanese design and art. Modern homes were redecorated with Japanese-style wallpapers and filled with kimonos and parasols, while painters—from Monet to van Gogh to Klimt—incorporated the Japanese style of flattened surfaces and skewed angles in their art. Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen was one of the artists in the 1900s whose style was influenced by Japanese art, particularly in his pictures of cats. Steinlen earned a living with his commercial artwork—book illustrations, restaurant posters, advertisements, and promotional posters—and he was also an active leftist, even an anarchist, whose radicalism sometimes got him into trouble. However, posterity knows him best for his most innocuous passion—drawing cats. Sinuous tabbies and black cats decorated his ads for chocolate and Nestlé cream, and he also would sculpt and draw cat portraits for his own enjoyment. Summer: Cat on a Balustrade is such a painting. Looking at this picture of a relaxed tabby sunning himself, you would never think that its creator, Steinlen, was a militant activist who spent time making propaganda posters.

One of the “calling cards” of the Art Institute of Chicago is the large painting (207.5 x 308.1 cm, i.e., about 10 x 6 ft), A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884 by Georges Seurat—one of the most iconic French paintings. Once the original Impressionists like Monet and Renoir had broken the conventions attached to more realistic and academic painting styles, the visual revolution brought out other disparate styles such as Gauguin’s flat and outlined surfaces, van Gogh’s wild colors and impasto texture, and Seurat’s myriad of small dots. Today, we lump all these styles into one category—“post-Impressionist”—but in fact, each of these artists had a different vision of what a modernist painting style should be. Seurat’s visual approach, derived from printing techniques and color theories, was that the human eye fills in gaps and, therefore, is able to perceive an unbroken line or a blended color that would result from placing small dots of primary colors next to each other. His technique of stippling little touches of color may feel too contrived today (as well as requiring an enormous amount of patience), but the resulting shimmering images can still fascinate contemporary viewers. And yes, there are animals in this picture, too—a couple of dogs and small monkeys that bring some suggestion of movement and lightness to the otherwise unnaturally stiff and posed figures of people.

The Chicago museum has hundreds more images of animals—horses in European paintings and Chinese sculptures, cows in antique reliefs, and dragons and other fantastic creatures in religious artworks. And an animal hunt can start with the museum’s entrance, guarded by two famous lions sculpted especially for the museum in 1893.