Nina’s Euro Blog: Wandering around Prague

I went to Prague to look at paintings in museums, but I found out that the best art there is not necessarily on the walls inside but on the ones outside. In other words, there is so much architectural beauty to be found in the city’s buildings, streets, and views that it surpasses the art in collections. Let’s start with museums, though.

Czech National Gallery collections are placed in several historical buildings in Prague. Works from the Middle Ages through the 18th century are collected in palaces that comprise the Hradčany Royal Castle complex. The castle grounds cover over 100 acres of a hilltop, housing various palaces, the Gothic Basilica of St. Vitus, medieval streets, fortifications, and gardens as well as the Czech senate and the presidential office. Modern art from the national collection is displayed in the Trade Fair Palace. Built in 1928, it was designed for trade exhibitions. On the outside, it looks like a gray monolith of an office building, but inside it is light and airy, with oval railings and moldings of the Art Deco style.

The Old Masters collection combines several historic collections of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire era, including the so-called” Italian primitive school” as well as painting masterpieces from the collection of the aristocratic Lobkowicz family.

Highlights include an outstanding Rembrandt, Scholar at His Study, and Albrecht Dürer’s two charming Madonnas—the one with an iris flower and the famous, complicated, and colorful Feast of the Rose Garlands.

The modern collection displays a lot of German Expressionism’s works and some very good Czech art, especially by František Kupka (1871-1957), an artist who moved at the turn of the century from Symbolism to Abstractionism.

However, the canvases that brought me the most joy were two by Gustav Klimt.The Maiden from 1913 is very much in the style we expect from this artist—sinuous figures of women enveloped in a mosaic of colors and geometric shapes. This one differs from the well-known Klimt “gold” pictures in his choice of the color palette—this one seduces with the vibrant shades of purple and green.

Klimt’s Water Castle is one of 11 large, square-shaped pictures he created during his summer stays at Lake Attersee near Salzburg. The artist would roam the lakeshore and forests, dressed in a long robe that he favored for his painting sessions (his girlfriend Emilie Flöge was a fashion designer who designed such unrestricted, flowing robes as a reaction to the constraints of wire corsets, fishbone stays, and the high, starched collars of men’s shirts). Klimt’s summer landscapes stand in strong contrast to the Art Nouveau portraiture that he painted, often as commissions, in Vienna. These summer stays at the lake and the resulting, post-Impressionist, “traditional “landscapes seemed to be his escape from city life and the pressures of studio work.

The Klimt series of landscapes, painted with sharp colors of modern synthetic pigments (such as apple green or phtalo green), are all forceful, busy masses of greenery that can evoke different feelings—from wonder to uneasiness. Water Castle is a view of Schloss Kammer, a baroque palace that he painted from several sides. The low point of view from the water allowed the artist to devote the bottom half of the picture to reflections on the lake—an explosion of greens and light that evokes Monet’s views of Giverny.

In Prague, however, art is best experienced through walking the city. The experience starts with the incredible views of the city, cleaved by the wide Vltava river and joined by bridges that rival those of Paris. It’s a city where you can find any architectural style within a short walk. The Middle Ages left Prague its famous astronomical clock, as well as the Basilica of St. Vitus, which is at the center of the Hradčany Castle complex.

The original church dates to 930 AD. It was transformed into a present-day Gothic cathedral in the mid-14th century.

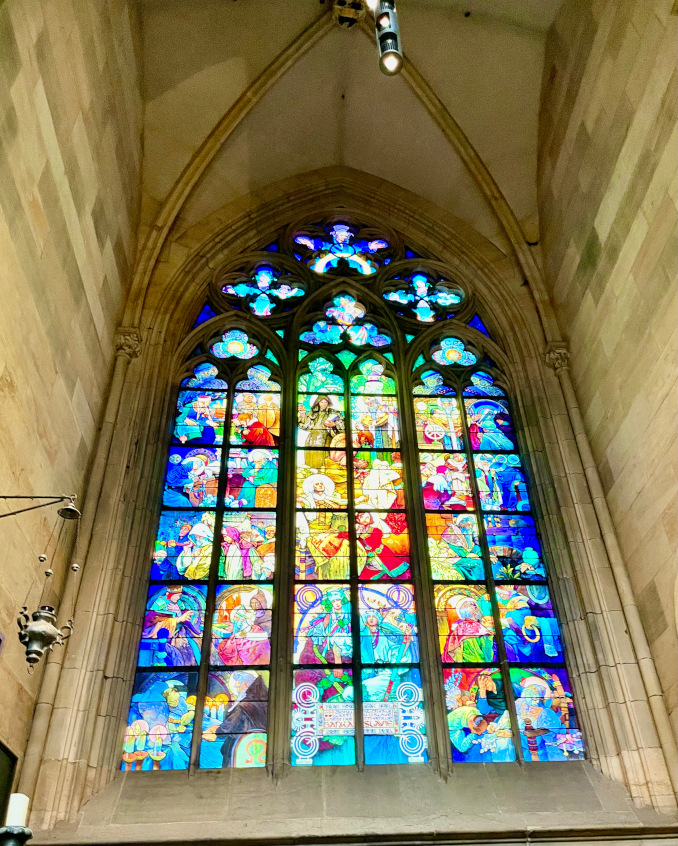

Even in this very old church, modernity can be found because one of the main stained glass windows was designed by the most famous Art Nouveau Czech artist—Alphonse Mucha.

Prague also houses Baroque churches, Renaissance houses of burghers, and above all, Art Nouveau buildings from the 1900s—the style that makes Prague’s historic center so distinct. Decorative details in this style are everywhere on houses throughout the older part of Prague.

In so many places, you can spot a little balcony with wrought-iron marigolds or thistle garlands, or you can admire carved doors, wrought iron banisters, or the facade of a building created with the full complement of moldings, sculpted details, and elaborate stonework of the 1900s—all of it preserved much better than anywhere else except perhaps Vienna.

Old Prague is a city to walk and look at buildings all day long….