Food for the Soul: A Year of the Dragon

By Nina Heyn- Your Culture Scout

In Asia, being born in a Year of the Dragon means to arrive in an auspicious year; dragons, in Chinese astrology, are symbols of power, good luck, and success. Western culture—the modern take from Game of Thrones notwithstanding—treats dragons as monsters to be vanquished. These two radically different views of the mythical creature are, of course, reflected in art.

Chinese culture started using dragons as symbols of power and divine blessings at least five millennia ago, as attested by stone carvings, decorations, and tomb jewelry. A Chinese dragon has the thin, sinuous body of a snake, but he walks on four paws with three to five claws, and he has a huge head, often with horns, bulging eyes, and a pearl in the middle of the forehead. He almost never has wings, but he spends a lot of time flying, trailing his long whiskers behind him. Since his permanent abode is usually in the heavens, he is often portrayed flying through clouds, only rarely landing on palace and temple roofs or in front of imperial palace gates. Water dragons live in rivers and seas, often protecting boats, sailors and swimmers.

As the most powerful creatures in Chinese mythology, dragons became emblems of imperial power. Elaborate dragon images would be placed on court robes and palace pottery, as well as being represented in paintings, sculptures, and architecture. With time, the dragon lore became very complicated, coming to include various types of dragons assigned different colors and attributes. Chinese dragons can be any color (e.g., black, red, or yellow), with each color signifying a different power; they can have horns or sometimes even wings, and they can embody various characteristics. For example, the Horned Dragon has two horns, his skin is covered with green or blue scales, and he can cause rains or rainbows to appear; the Fire Dragon is pushy, and the Metal Dragon is virtuous. All of this huge variety in dragon lore was reflected in Asian art for millennia.

At the Qing dynasty court (1644-1911), all formal robes and accessories would be adorned with color-coded and number-prescribed dragon designs, serving in this way to distinguish the rank of court officials. The regulation of iconography was strict; for instance, officials of the fourth to sixth rank were assigned robes with eight dragons, each of them with four claws. The imperial “dragon robes,” which were known as jifu (i.e., “festive dress”), were full-length coats embroidered with pictures of dragons, accompanied by auspicious signs and religious emblems. For an emperor, the reserved color was bright yellow, and the exclusive design included nine dragons with five claws. A detail of such imperial embroidery is shown above.

In China, dragons have continued to be a symbol of government’s power and prosperity in more modern times. In the last decades of the Qing dynasty the 19th century, the state flag would bear just such a symbol, a lively azure-colored dragon on a yellow background, making one of the most artistic flags in history:

Dragon iconography also trickled down from the splendor on display at court to less elaborate artifacts produced for the lesser nobility and officials as well as the merchant class. This beautifully painted porcelain plate shows two dragons chasing a flaming pearl—a classic motif symbolizing the pursuit of wisdom and spiritual energy.

(Kangxi reign mark). Porcelain, enamel, iron oxide. National Museum, Warsaw. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Dragon tales would be told to children, dragon statues would be used for decoration of homes and public spaces, and dragon images would decorate holiday wares, clothing, porcelain dishes, and writing sets. Because the dragon is a mythical creature, he is also considered most suitable for a traditional decoration placed on roofs to protect abodes from fire and bad luck. Until the present day, dragons, together with the phoenix and qilin (a type of horned chimera), are posed on roof corners, usually as small, ceramic or wooden monochrome statues. On this temple roof, however, the clay figurine is brightly painted and unusually large.

Japan and the rest of Asia share the Chinese iconography of dragons as snake-bodied, luck-bringing celestial creatures. As such, they have decorated warriors’ armor (for luck in battle), ships and boats (to protect them from sinking or losing in a race—dragons control water), and statues guarding important buildings.

Japanese master Hokusai (1760-1849) is best known in the West through his indigo and white woodblock prints of landscapes, with The Great Wave being the most iconic. Even if his fame both in Japan and in the West sprung from these woodblock prints, he was also a painter and book illustrator. This snake-like dragon was painted by Hokusai when he was in his eighties. It is a decoration of a boat ceiling that he painted as a commission from a local merchant when he was living in the countryside. It is just a decoration of a festival float—by definition an ephemeral object—and yet this is such a perfect picture. Up until his last days, Hokusai was in search of mastery in his art, and this is clear in this “decorative piece” when you study the contrasting red and gold color scheme, the pattern of scales, and the coils of the dragon encircled by tiny waves. The best is the priceless expression on the dragon’s face—he looks like a family dog who has swallowed a forbidden piece of meat—sly and a bit worried. This dragon is an individual—not just a symbol of good luck.

A dragon is not only a perfect image for paintings—it lends itself to three-dimensional art forms such as sculptures. Metal dragon figurines were produced in Japan for centuries, especially after the demand for swords dwindled and master metalsmiths had to come up with other products to keep their craft alive. The fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868 forced both samurai warriors and their armorers to seek new ways of life. The warriors became rōnin or government officials, and the metalworkers started making perfect sushi knives and iron decorations. Metal figurines with articulated parts—usually animals such as dragons, birds, and insects—became very popular decorative items in Asia, and they are still widely offered today.

Sometimes, the two pictorial traditions of an Asian dragon with a long snout and pointy horns and the winged dragon known in the West as Saint George’s opponent would merge together, as in this Ethiopian painting from an 18th-century fresco. It’s an image of the saint spearing a dragon, but the animal is clearly inspired by Asian iconography, perhaps thanks to the international trade on the east coast of Africa.

In the West, dragons have been around for a long time, too, but they look different and exhibit different behavior. They have wings (even the Celtic dragons shown in monastic manuscripts), and they spew fire. A Western dragon is not a water snake or a heaven dweller—instead, he lives in caves, usually demanding tribute in the form of a sheep or the occasional virgin. Sometimes he guards treasure, but more often than not, he is just a nuisance that needs to be chopped down by an itinerant hero.

In Western lore and its subsequent interpretations, dragons almost always serve as a depiction of negative forces to be conquered. When they do guard something, it is either their own treasure or, in the case of Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece or the Hesperides’ golden apples. They are not friends of people; they are monsters personifying psychic bonds that need to be relieved by “slaying”—they may embody the oppression of people who need to be liberated, or a trial that proves the worth of a knight.

All this is reflected in Western iconography, often tied to the myth of Saint George. The original George is believed to have been a Roman soldier who was martyred sometime in the 3rd century AD for his refusal to renounce his faith. His connection to the dragon came much later, in the 11th century, through a legend of a knight who saved the city of Silene (present-day Libya) when he slayed a monster poised to devour a princess. A similar version of this legend also had been circulating in many other European locations. (In the Polish city of Kraków, you can even visit a dragon’s lair where the beast apparently used to reside underneath the ramparts of the royal castle.) By the late Middle Ages, the tale of a savior saint who had lanced a dragon to save the city (and a princess) had become firmly embedded in literature and art. Eventually, the legend was fused with the story of the Christian martyr, canonized in 494 AD, and by the time of the Crusades, Saint George had become a model knight defending Christendom against the infidels. This is perfectly illustrated in numerous Renaissance artworks.

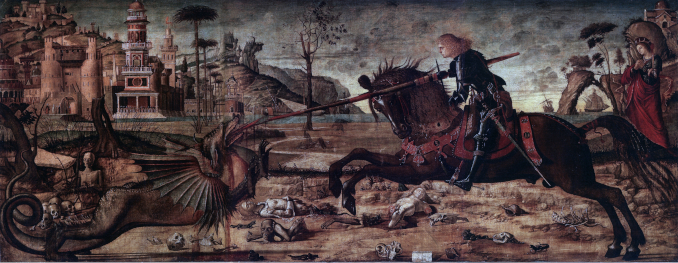

At the beginning of the 1500s, Venice was a bustling center of global trade. The city’s prosperity and its prominent citizens had been well recorded by Titian and later Tintoretto and Veronese—those giants of sumptuous and colorful Venetian paintings. Though Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460-1525), a Venetian artist from the generation that preceded them, ended up being less prominent in art history, appreciation of his art is growing, especially after the spectacular 2019 restoration of his cycle of nine Saint Ursula paintings, now displayed in their original splendor at Venice’s L’Accademia.

Like all artists of his time, Carpaccio painted his share of devotional artworks and altars, but the most delightful are the canvases he did to decorate the walls of scuolas (fraternities that were the backbone of the Venetian society). These works included mythological scenes, biblical episodes, and stories of saints. Carpaccio was a compulsive recorder of the world around him—if he were alive today, he would probably be a photographer or a documentalist. His paintings are full of details of clothing, plants, animals, and objects—ranging from horse tacks to building friezes. You can spend hours just looking the Saint Ursula cycle.

Carpaccio created the cycle of nine paintings for a fraternity devoted to Saints George and Trifone. Two of those works, including Saint George and the Dragon, were actually paid for by a man named Paolo Valaresso, a military commander of Venetian fortresses which had been lost to Ottoman Turks in a war between 1499-1503. Even though Saint George and the Dragon shows a religious tale, it was inspired by the contemporary conflict waged between Venetians and Turks. The painting of St. George, who vanquishes a population-terrorizing dragon (the terrified princess hangs in the back), is, therefore, an allegory of a military threat that preoccupied Venetians at the time. St. George’s bravery would have been read as Venetians’ hope for a Christian victory.

Painted in 1518, a classic example of the St. George iconography, St. George and the Dragon by Sienese artist Il Sodoma (1477-1549), shows the saint spearing the writhing green dragon with the requisite princess-in-distress prominently displayed in opulent red and yellow silks. The artist only veered off-canon by painting the horse brown as it is represented in the Greek Orthodox tradition. In Catholic paintings, the steed was usually painted white, as in “a knight on a white horse,” symbolizing righteousness.

Like Il Sodoma, Jacopo Tintoretto (c. 1518- 1594) was an artist whose style belongs to Mannerism—a transitional style of the late Renaissance, characterized by complex and startling compositions, twisted bodies, exaggerated gestures, and sometimes garish colors. In this painting from 1555, St. George (on a traditional white horse) is indeed busy with his prescribed role of slaying the dragon, but the vertical composition of this picture draws our attention to the pretty princess. At the top of the picture (i.e., farthest away) is the image of God, who is spurring his saint to action, while the dragon-killing business takes place in the middle, but closest to our eyes is that damsel in distress, clothed in gorgeous hues of lapis blue and Venetian ochre reds. This is a truly Venetian painting—the prominence is given to a beautiful woman in flowing, colorful robes.

Chinese emperors were not the only ones to refer their ancestry to mythical dragons. In this portrait, the appearance of a dragon serves to remind viewers of the Welsh heritage of King Henry VII. The members of his family are aligned on both sides, but the top of the symmetrical composition depicts an impressive green dragon, rearing up after being speared. The underside of his belly and his hind legs are quite similar to those of a greyhound—after all, the artists would probably have had hunting dogs as perfect models for the animal body.

Modern depictions of St. George and the dragon have often abandoned the straightforward dichotomy of the invincible and righteous knight versus the vile beast personifying evil or an enemy. These modern renditions focus more on the internal struggles of both the man and the beast.

An illustration from a G.K. Chesterton book published in 1914 shows the exhaustion of all three protagonists: the dragon is presumably dead, the knight lays exhausted beside his adversary, and a lifeless horse completes the trio. All three lie slack and intertwined—there are no victors in this battle. What a prescient illustration it was, created on the eve of the Great War.

Odilon Redon (1840-1916)—an unappreciated French symbolist—places the slaying scene in the surreal world of a beach or river bank, lit by an enormous bloody sunset, with water spilling down like at Niagara Falls. Redon himself became a Buddhist, and his iconography comprises in equal measure Christian imagery, mythology, and Buddhism, so perhaps this eclecticism of beliefs helped him to free the image of its traditional connotations. Rather than portraying a victorious man triumphing over a monster, this image looks more like a solitary man trying to beat down a slithering beast toward the water—a man pushing unwanted thoughts toward the vast ocean of the unconscious, perhaps? Beautifully painted, this is a picture that leaves it to the viewer to imbue it with personal interpretations.

And last but not least…

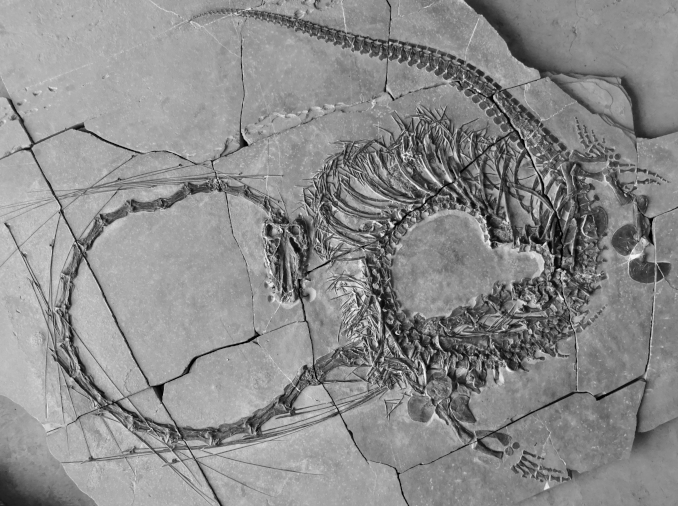

So far, we have talked about dragons as mythical creatures, but it turns out that the Chinese images of dragons as water snakes—these giants twisting in roiling waters—were not necessarily much off course from reality. In 2003, a fossil of a new dinosaur species, Dinocephalosaurus orientalis was found in southern China. In 2024, Scottish paleontologists published new findings about this creature. Both the fossil imprint and a 3D reconstruction of this new species’ body show us a classic Chinese dragon with a sinuous body and triangular head.

So, maybe dragons are not entirely mythical, serving our psychological need for powerful creatures to give us a sense of victory if we overpower them or a sense of security if they swoop down to rescue us? Perhaps dragon myths and images are our collective genetic memory of times past? Carl Jung might have something to say about it.