Food for the Soul: Stories of Women at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Philadelphia’s main art museum was established in 1876 as part of the centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence. Since then, the Philadelphia Museum of Art (we’ll call it PMA for short) has been expanding its catalog to its current grand total of almost a quarter of a million objects, purchasing and inheriting numerous collections of armory and furniture, textiles and costumes, sculptures and pottery, and prints and antiquities. Part of the museum has recently undergone a remodeling by Frank Gehry, the master of contemporary architecture, who introduced modernity with light wood paneling, re-established long passages and a graceful staircase.

Like the Met in New York or the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a cultural destination that merits numerous visits to explore its halls for all kinds of visual treats. I visited PMA searching for women, both as creators and on canvas. Some of the artists in PMA’s collection—Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Rosa Bonheur, and Georgia O’Keeffe—are the protagonists of my book, Women in Art: Artists, Models and Those Who Made It Happen, which will be published this year. Let’s take a look at some of the pictures by these artists that you can find in Philadelphia.

In May, the PMA will launch an exhibition devoted to Pennsylvania’s hometown hero—Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), who was born in Allegheny. Even though she spent most of her life in Paris, she came from a prominent Philadelphia family. Cassatt was a late bloomer in art. After leaving America, she spent several years studying and traveling in Europe, eventually settling in Paris. There, she succeeded in having some of her works accepted at the Salon—an annual exhibition that was the prime venue for recognition and access to collectors and critics. Her first picture, Two Women Throwing Flowers During a Carnival, inspired by her visit to Spain, was accepted by the Salon in 1872 and initially, it seemed that this American-born, female artist had a chance at a career within Paris’s art establishment. Afterwards, however, Cassatt experienced several years of Salon rejections; embittered, she accepted Degas’s invitation to exhibit with the new group of younger artists who eventually became known to us all as “Impressionists.” In 1879, presenting 11 paintings at this exhibition, this 34-year-old “American in Paris” debuted as one of the representatives of a style that has become one of the most influential in the entire history of art.

PMA’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge is one of the original 11 paintings exhibited and one of the few Impressionist works that the Paris press welcomed that year: “Mlle. Mary Cassatt is fond of pure colors and possesses the secret of blending them in a composition that is bold, mysterious and fresh.” With this exhibition, Cassatt found her artistic path.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge and another painting at PMA—A Woman and a Girl Driving—feature the same model: Mary’s older sister Lydia, with whom she had a very close bond and shared her life in Paris. Lydia was ailing and never married, instead being Mary’s companion and running her Paris household for many years. Driving (the original title of this canvas) is painted as a photography-inspired close-up, showing a woman not as a passenger but holding the reins (the little girl next to her is Degas’s niece Odile). This is what draws me to this picture—it is a portrait of a woman in charge. As a city dweller, I originally assumed the man in back was a passenger, but I was wrong. In fact, I owe my enhanced understanding of this image to a Pennsylvania lady who fortuitously also is named Lydia and is an equestrienne who participates in carriage events. She explained to me that in this picture, the man in the back would have been a footman whose role was to jump out and hold the horse while the driver and her passenger descended. The art of carriage driving and horsemanship are still very much alive in the countryside of Cassatt’s native Pennsylvania.

It is not easy to find specific works by women artists in the vastness of PMA’s marble halls. It took a lot of wandering to find a painting by one of my heroes in the history of art. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) had arrived at the pinnacle of success as a court painter of Marie Antoinette but was obliged to reinvent herself during a long political exile after her dramatic escape from revolutionary mobs at the start of the French Revolution. From teenagehood on, she had been forced to live by her wits and her enormous talent, first supporting her family after the death of her father and then taking care of her daughter during the long years of her peregrinations across Europe—the typical fate of a political emigré. Le Brun’s Portrait of Madame du Barry belongs to the early career of the artist when she enjoyed the French queen’s patronage and commissions from courtiers who were eager to have a flattering portrait from a young and popular artist. Her model, Madame du Barry, has an unusual biography as well. She started her Parisian life as a milliner, hairdresser, and courtesan, but soon her exceptional beauty caught the eye of her aristocratic clientele. Eventually, she became the last official mistress of King Louis XV, but her commoner origins did not endear her to the king’s princely daughter-in-law, Marie Antoinette. Court squabbles were nothing, however, compared to what awaited both women with the advent of the Revolution. Like the queen, Madame du Barry was imprisoned and guillotined by Jacobin guards. The irony, of course, is that du Barry was as much (if not more of) a proletarian as her persecutors, but she died an aristocratic death. When the winds of history blow, it is usually better to flee, as Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun did, than to resist the changes, as poor Madame du Barry did.

It seems that almost every biography of a woman artist is a story of a person who bucked convention or overcame great odds. Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), the perennially popular “giant flowers” artist, did not have to struggle too much to get established because she was already exhibiting when she was in her twenties. O’Keeffe’s struggle was more with herself and with the pull of art movements that exploded in the first decade of the 20th century—just as she was graduating from art school. It would have been tempting to paint in, say, a Cubist style, which was the latest trend just coming in from Europe, but this American artist saw the world in a different way. From the beginning, her paintings—watercolor landscapes, charcoal abstracts, or her first oils—were done in her characteristic style of vivid colors, sinuous but clean lines that are precise and almost graphic, and her macroscopic perspective.

Until she discovered the New Mexican deserts and made those arid landscapes her main source of inspiration, O’Keeffe lived in a high-rise apartment in Manhattan. The painting in PMA’s collection called Orange Streak is from that period. She painted it in New York, but it is actually a reminiscence of her time living in Texas, where she witnessed an electrical storm with lightning crisscrossing the sky. That violent visual experience translated in her mind into this arresting abstract of oranges and yellows against a dark background. This beautiful abstract composition is as characteristic of O’Keeffe’s style as the pictures of skies over Santa Fe that she would paint 60 years later.

Searching for women in the PMA’s collection also means looking at the models in paintings. Here are a couple of women models with particularly interesting stories behind them.

Poet, writer, and art dealer Léopold Zborowski did not have too much of a head for business, but he was a likeable art enthusiast, gambler, and man who liked to help his artist friends who drank too much while doing avant-garde pictures. “Zbo” emigrated on the eve of WWI from his native Poland to Paris. After a brief internment as an “enemy combatant” (he came from the part of Poland under Austrian occupation, which technically made him a French enemy), he started his career as a marchand, trying to sell the artworks of his new bohemian friends: Maurice Utrillo, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall, André Derain, and Amedeo Modigliani. Representing an artist in those days perhaps called for more-ranging duties than it does today. “Zbo” gave Modigliani one of the rooms of his two-bedroom apartment, paid his bills, bought him paint, and had his wife pose for him.

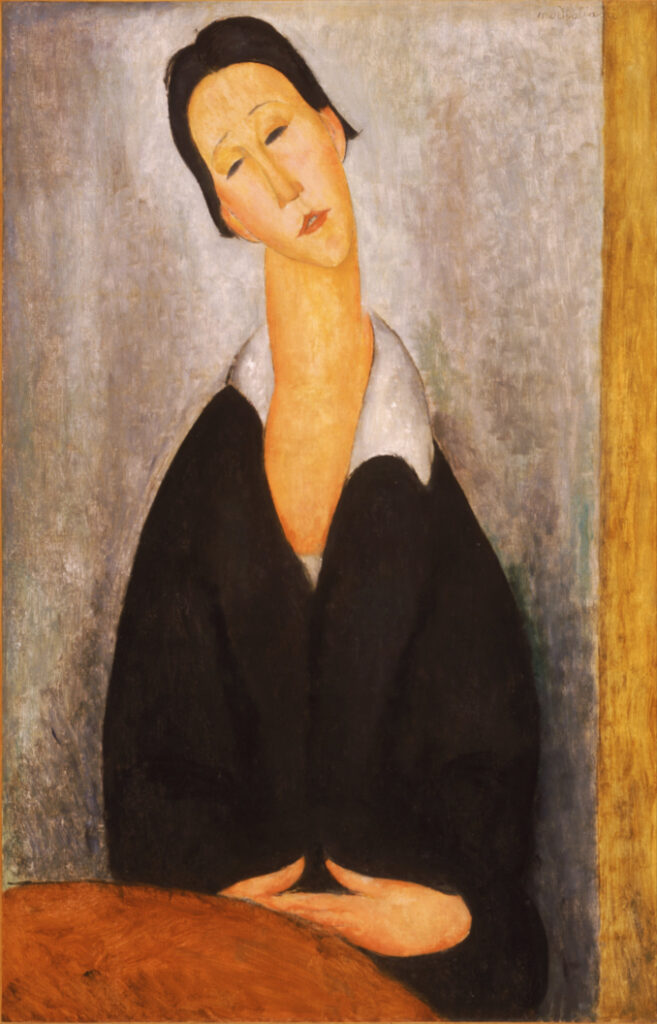

Anna (“Hanka”) Sierzpowska was a Polish noblewoman who was probably not actually married to Zborowski, but she lived with him in Paris in the 1920s. She is the person portrayed in Modigliani’s Portrait of a Polish Woman—a dark-haired woman in a black dress with a white collar (those romantic triangular collars came into fashion at the end of WWI). Modigliani’s style of stretched-out lines and facial features barely marked with a few lines was influenced by African masks (they had started to show up in the souvenir shops of Paris, and the Paris bohème began collecting them) and folk art in general, but you can also find in this painting some echoes of Parmigianino’s Madonnas with their famous elongated necks and bodies.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) had always wanted to be a history painter—the genre most prized in a Europe transitioning from Enlightenment to Classicism at the very end of the 18th century. In 1801, this young French artist won the most prestigious art scholarship of the day, called the Prix de Rome, but he had to wait five years until the prize was sufficiently funded for his multi-year stay in Italy. Commissions for large historical canvases were not easy to secure, and even though in his long career Ingres painted a good share of them, in the early days he made his living painting aristocrats or government officials and their wives. Ironically, though Ingres was most passionate about his mythological and historical tableaux, what art history has most remembered him for are his portraits of portraits of society ladies and the odalisques that he painted when Orientalism came into fashion. Picasso adored Ingres for his portraits of beautiful women, like Madame de Moitessier, which he referenced in his Woman with a Book in 1932.

Ingres painted his Portrait of the Countess of Tournon during his stay in Rome, when the city was occupied by the Napoleonic armies. In fact, it was Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt and Syria that introduced the fashion for the types of Indian shawls with a paisley design that the comtesse is wearing. For Ingres’s style of painting, though, the honesty of this image is its most astounding characteristic—we see the countess with her bulging eyes, a nose that is a bit too large, and a faint mustache over her lip. Ingres is not beautifying her. Rather, it is her intelligent gaze, knowing smile, and general look of a sophisticated woman who is sure of herself that endear us to this person. This is a brilliant psychological portrait—much more interesting than the Neoclassicist perfection that Ingres was so keen on propagating throughout his career.

An afternoon stroll through a large museum is never enough to uncover all of its treasures, and visiting this one was no exception. I had to walk past works by women artists like Judith Leyster, old masters like Nicolas Poussin, and unique visionaries like Henri Rousseau. I could only pick and choose but a few of the many stories that PMA’s pictures can tell.