Food for the Soul: The Barnes Foundation – Transitions

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“Appreciation of works of art requires organized effort and systematic study. Art appreciation can no more be absorbed by aimless wandering in galleries than can surgery be learned by casual visits to a hospital.”

~ Albert C. Barnes

When Dr. Albert C. Barnes—physician, inventor, chemist, entrepreneur, and one of the greatest collectors in art history—embarked on his adventure with art in 1912, he could not have predicted the hundreds of thousands of visitors who now go through the doors of the Barnes Foundation each year. In fact, when he established the foundation in 1922, he originally envisaged his galleries as a resource for small circles of researchers and students. The world changes, however, and after his passing in 1951, the fabulous trove of modern, mostly French, artworks became the object of a legal tug-of-war. Despite what was specified in Barnes’s will, in 2012 the collection was moved from its original location in the small town of Merion to the center of Philadelphia.

Even if this move defied the collector’s wishes, perhaps art lovers and the artworks themselves have benefited. What Barnes could not have predicted in the less crowded, more genteel, and less polluted world of the 1940s was that the new construction could protect his collection with modern light, climate control, and better security (today, museums are endangered by both thieves and activists alike), while offering educational access to more people, many of them the ones he cared about the most—members of the general public who do not have mansions filled with artworks or the means and knowledge to travel to distant art museums. If his goal was to bring fine art to non-elites, the move to the center of town has made this possible.

Barnes had very specific ideas about arranging all his paintings in thematic groups, accompanied by relevant historical artifacts (e.g., early American metalworks, Native American jewelry and pottery). These arrangements, down to the smallest detail, were reconstructed after the move, so that even today you can study Barnes’s vision and the intellectual connections that he made between various artworks. However, as I was recently wandering through the recreated halls of the Barnes Foundation, I wanted to make my own connections—and I was struck by the various transitions that these paintings document.

What Women No Longer Do

In keeping with this year’s Food for the Soul theme, “Women in Art,” I was looking at paintings that show women doing things that have disappeared as activities or have profoundly changed. It did not hurt that these paintings happen to be some of the finest examples of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art.

Today, we might dub Édouard Manet (1832-1883) a “high-concept” artist for his deliberate pivot toward modernity. It started with his Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe)—a painting that caused outrage when first exhibited in 1863. Manet’s idea of showing modern people (naked “working girls” next to dandy gentlemen) scandalized critics and art lovers, who expected nudity in mythological canvases but not in images of daily life. Laundry, painted a good 10 years after Manet’s scandalizing debut, is a much tamer subject. A woman is doing a small wash—just a few pieces of clothing in a wooden pail, set on a chair in the garden. A toddler is “helping” nearby. This is an outdoor scene, and Manet makes the most of the light shining on wet cotton blouses. His choice in capturing a moment of mundane activity, not as a cute genre piece but as a “snapshot of life,” is what distinguishes Impressionist art from the realism of the late 19th century.

We still do laundry—and women, especially those who have small children, really do that all the time—but we rarely do major laundry by hand and certainly not in wooden buckets. The invention of the washing machine is one technological invention that any woman will praise.

When they were poor, Camille Monet often modeled for her husband Claude (in one of his paintings, she posed as three figures), but in this one, known as Madame Monet Embroidering, she is captured not as an anonymous model but simply as herself, doing a large-scale embroidery. She is concentrating on her work, seemingly oblivious to both her husband painting her and the beautiful patio setting which Monet rendered with meticulous brushstrokes. Similarly to Vermeer’s The Lacemaker, this is not an image of a woman who has to work with her needle to make a living. In the decades leading up to maybe the 1950s, this was a common pastime for women at home. Embroidery is still an “at home” activity (these days categorized as “hobby crafting” and sustaining a good segment of the DIY industry), but it has become a skill less and less practiced. In my childhood, embroidery was an obligatory skill a girl would learn from women in the family; these days, it is a rare activity learned from TikTok videos.

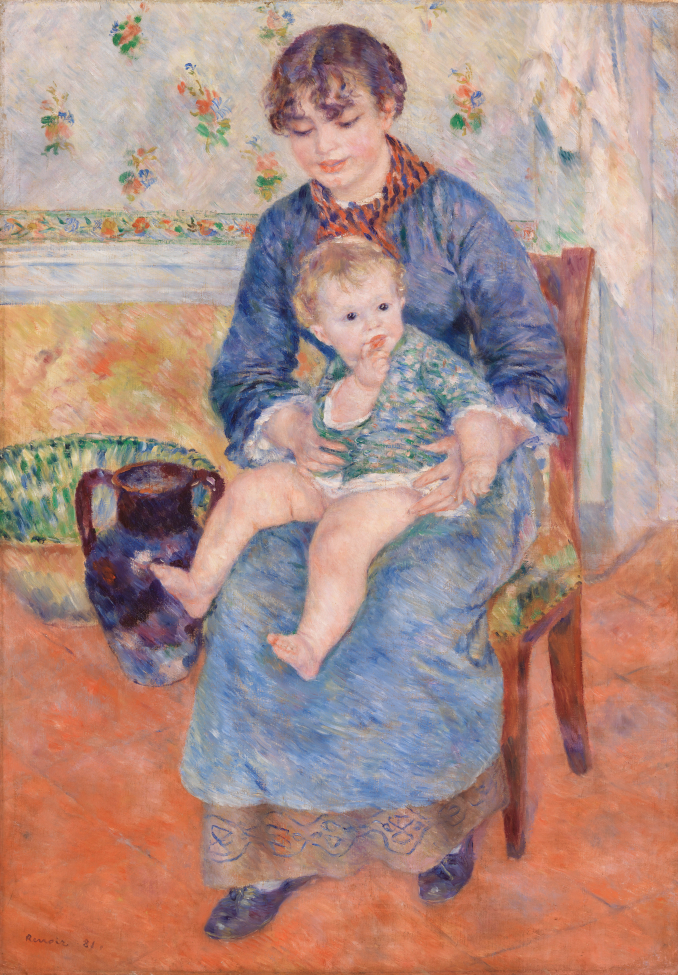

When sometime around 1909 Renoir posed a dark-haired beauty in a pomegranate-colored blouse to sit down and repair holes in socks, such an activity would have been among the most common. However, darning is another skill that has nearly disappeared with the last century—we repair things less and less, and women certainly do not spend their evenings darning holes.

Changing Styles: The Case of Renoir

The Barnes Foundation is famous for its abundance of 181 Renoir artworks—the largest single collection in in the world. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), the most famous of the Impressionists, lived a long life and created about 4,000 works. Living to the ripe old age of 78, he witnessed numerous political events, from the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 to the First World War. He was a co-founder of one of the most famous art movements, and he became a mentor to subsequent generations of artists.

During his long artistic career, Renoir changed the style of his paintings several times. His earliest mature pictures are part of the Impressionist credo of capturing the actual light, colors, and scenes of life outside the academic ateliers. Consequently, Renoir and his fellow Impressionists would use fast, “sketch” brushwork of unmixed, bright paints from the newly-invented tubes, and they would work outdoors and strive to portray contemporary people during daily activities. Not everything about their craft was a spontaneous burst of creativity though—they would still finish pictures inside their studios (Renoir much more than, for example, Monet), and they would carefully stage compositions by using models and props.

When in 1879 Renoir painted Luncheon, he was in a way referencing old Dutch Baroque genre paintings of people sharing a meal inside a house or a tavern. In this picture, a couple is sharing some wine, with bread and a silver soup dish nearby, but only those elements would refer to old masters’ paintings. Otherwise, the setting is entirely contemporary to the artist’s Parisian life—the bread is a baguette, the couple are on a boating outing (indicated by the straw hat, home wine, and the décor of a country restaurant), and the informality of this midday meal is typical of some of Renoir’s most famous pictures, especially his 1881 masterpiece, Luncheon of the Boating Party.

In the same year of 1881, Renoir—no longer a struggling artist—could finally afford to travel to Spain and Italy. His encounter with Michelangelo’s and Raphael’s frescoes propelled the artist toward a different style, which modern art history has dubbed “harsh” or sometimes his “Ingres phase.” The artist abandoned the truly “Impressionist,” fuzzy transitions between colors, and the marking of canvas with sharp daubs of paint, in favor of smooth lines that were modeled after the Renaissance style he studied on his travels.

He painted The Artist’s Family in 1896 in this old-masters-inspired style. The composition descends from the tradition of formal, multi-figure portraiture (including the most famous group portrait in Las Meninas by Velázquez, which the artist had studied at the Prado a few years earlier), but that’s where the connection to the 17th century ends. Renoir, painting at the very end of the 19th century, may have been showing us a staged scene (and after all, what portrait isn’t carefully arranged?), but the setting is decidedly modern and informal. Renoir’s wife and children are wearing colorful clothing (perhaps a tad overdressed for a backyard garden), the neighbor girl is still holding a toy ball but already preening in the direction of the boy, and the nanny looks less of a servant than a loving and loved member of the family.

In the last few decades of his life, Renoir’s style changed yet again. He experimented with some elements of Post-Impressionism (especially the style of the young Cézanne, who visited him and painted alongside him), but he settled on a smooth style, later dubbed “pearly,” that emphasized his favorite pink of the glowing skin and auburn shades of hair, all painted with the smoothest lines possible. In that last period, he mostly painted nudes or children—the two subjects that endlessly fascinated him thanks to their beauty, the luminescence of young skin, and abundant locks of fine hair. The 1910 After the Bath is a perfect example of this style, and the Barnes houses many more of these pictures.

The Advent of Modernism

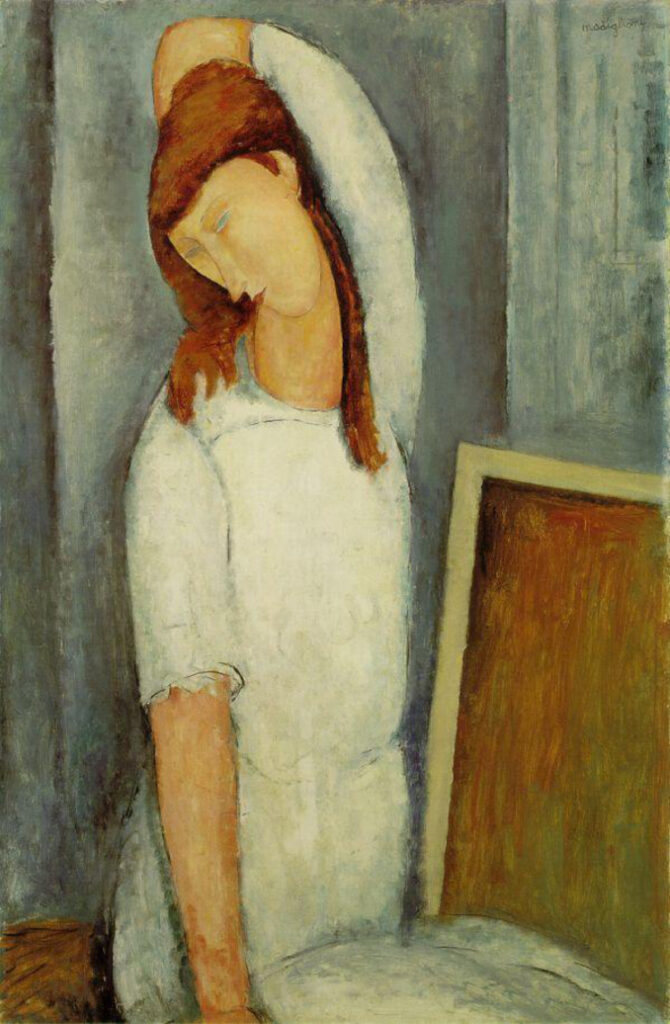

In 1912, Barnes—whose pursuits as a doctor and inventor had turned him into a self-made millionaire—started his new adventure as an art collector by sending painter William Glackens to Paris with $20,000, tasking him to buy some Renoir and Sisley artworks for him. Glackens raided the galleries, quickly acquiring 33 paintings, including some Renoirs but also Cézanne’s Toward Mont Sainte-Victoire and van Gogh’s The Postman. From that point on, Barnes was bitten by the collecting bug; just a few months later, he followed Glackens to Paris and started to acquire Post-Impressionist canvases at a breathtaking pace. Barnes could easily have focused on the typical subjects that deep-pocketed American customers searched for in European galleries: Italian landscapes, Dutch genre scenes, and works of French Academism. Instead, he preferred to buy Matisse and Cézanne, as well as Picasso, Soutine, Braque, and Modigliani—his contemporaries—who were literally creating modern art at the same time he was building his collection.

During the decades of his annual purchasing trips to Paris (interrupted only by the two World Wars), Barnes acquired hundreds of French pictures, many of them the best and most representative of the painters who pushed art toward 20th-century modernity. You can literally learn art history from looking at these pictures. When Barnes established the Barnes Foundation, declaring as its aim “the promotion of the advancement of education and the appreciation of fine arts,” he had this goal in mind.

When Cézanne was exhibiting his works in Paris in the last two decades of the 19th century, his work was met with incomprehension by the public and derision from most of the critics. “Nothing to say about the paintings of Cézanne. The painting of a drunken cesspit emptier,” elegantly wrote one critic. The only people who admired Cézanne almost from the start and who, openly or covertly, collected his paintings whenever they could, were painters themselves: Renoir, Pissarro, Degas, Matisse, and Gauguin. They knew that this loner from the south was onto something they were all in search of—how to show things from the point of view of an artist rather than the point of view of convention (e.g., a formal portrait, soon to be replaced by photography anyway) or the point of view of expectation (sky has to be blue and grass green) or the point of view of tradition (a historical tableau is an important painting, but a picture of three apples isn’t). Cézanne broke all of these conventions, at the same time painting those sublime arrangements of fruit and landscapes that pull at your heartstrings.

Cézanne’s Still Life above, one of his many compositions of apples on a table and one of a dozen in the Barnes collection, is a perfect example of this transition from the “old” art to the art that exploded in the 20th century. Since the Renaissance, every artist had striven to paint according to the laws of perspective, with one point of view that could be traced with straight lines. But Cézanne understood that our eyes constantly move when we look at something, that each eye sees a different part of the picture (they get merged in our brain), and that we rarely view anything from one ideal perspective point. Our eyes gather information differently than the strict rules of painting would have us believe. This is why the table in this picture is slanting; the ceramic pot is shown straight on, but the tabletop is tilted toward us. Once we forget about the conventions of perspective, we can enjoy what this picture is really about—an exuberant orgy of juxtaposed color—with all those oranges, yellows, and greens grouped like models on stage. Renoir was so right when he once asked fellow painter Maurice Denis, “How does he do it? He can’t put two strokes of color on a canvas without it being very good.”

Masterpieces that fill Barnes galleries—Picasso’s The Peasants or Modigliani’s Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne—are perfect examples of art’s changing role. No longer serving to illustrate, 20th-century art became the means of expressing an artist’s individuality, using radically different means—whether simplified “childish” pictures, violent color juxtapositions, or images that might have been meaningful to the painter but incomprehensible to a casual viewer. This is especially evident in Matisse’s paintings (Barnes has a collection of 59 of them), including some of his most magnificent works such as The Music Lesson and The Joy of Life. These images are still in copyright, but you can get an idea of how Barnes arranged his Matisse treasures from this installation.

Exploring the galleries of the Barnes Foundation is all about transitions—changes in styles of art, changes in perspective from 19th-century realism to artist-oriented individualism, and changes in the realities reflected in these images. A day spent at the Barnes is a day spent in an art school.