Food for the Soul: London Exhibition “Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920”

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

This summer, the Tate Gallery in London is presenting an exhibition entitled “Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920,” showcasing 400 years of women creating art in Great Britain. Some of them, like Artemisia Gentileschi and Angelika Kauffmann, came from other countries in search of clients and patronage, some of them, like Maria Cosway, achieved success, and some of them, like Mary Black, failed to attract clients and have largely been forgotten, despite talents showcased by this exhibition. If there is one theme that unites all these different painters over the centuries, it is their struggle to secure recognition among their peers and clientele. You could almost subtitle this exhibition “Knocking on closed doors” because there were so many examples of failed careers and attempts to breach the glass ceiling of membership in the Royal Academy.

This struggle is most evident in the biographies of artists active in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century. The year 1780 marked the opening of the Royal Academy in London—the ultimate body of artistic recognition and professional access. Two women were among the founding members: Angelika Kauffmann (1741-1807) and Maria Moser (1744-1819). Because only a few flower compositions of Moser’s have survived to our times, we will never know whether she was an accomplished painter in her own right or whether her admittance was helped along by her father being an Academy member. Kauffmann, however, was an internationally celebrated painter of the prized historical genre, and her place in art history is assured thanks to her unquestionable artistry. The exhibition showcases Kauffmann’s Color, an ingeniuous allegory of colors as a painter’s tool—a picture where a muse draws pigments directly from a rainbow onto her brush.

You would think that after such an auspicious start, there would have been a steady progression of women admitted to the Academy, keeping pace with their achievements of winning exhibition awards, securing prestigious commissions from aristocratic clientele, and winning critical praise for ambitious works. However, the next time a woman got admitted to full Royal Academy membership was in 1922. In the intervening 142 years, women created, contributed, and won praises—just not the full professional recognition. Consequently, their efforts to make a living as painters were often thwarted. Either they would not get high-priced commissions (such as church decorations, aristocratic portraiture, or historical and allegorical paintings for public buildings) or they would be underpaid or even forced to submit their work under the name of a male relative or teacher.

Here are just a few examples of such women.

Messenger Monsey was a famous London physician who commissioned Mary Black (c. 1737-1814), a talented student of Joshua Reynolds, to paint his portrait. She created a psychological portrait of a man deep in thought and a picture so individualized (in an era of bland pictorial formality) that we still stop and admire it centuries later. The client was not happy, however. Black had modestly asked for 25 pounds—half of Reynolds’ usual fee—but this request for payment outraged Monsey, who believed that giving a woman the opportunity to paint his picture should be payment enough. Black backed down, saying that a quarter of Reynolds’ rate would be satisfactory or even “whatever (he) thought proper,” but Monsey’s outrage did not abate and he denounced her in his letters as a “slut.” Black’s career never really recovered from this episode; she moved on to exhibiting works in pastel (a medium considered appropriate for women but not serious enough for “real” artists), and eventually she became an art teacher. Black’s misadventure demonstrates how difficult it was for female artists to achieve financial independence when their skill and value were judged through a prism of gender rather than achievement.

Maria Cosway (1760-1838) succeeded Angelika Kauffmann (who went back to the continent in 1781) as the most prominent 18th-century woman artist in Britain. She was brought up in Florence (her parents catered to British travelers on Grand Tours in Italy), and when she arrived on the London artistic scene she was already well-educated and well-connected in the art world. Upon marrying the society artist and royal portraitist Richard Cosway, Maria gained access to lucrative orders from high-profile clients, and the Cosways became a fashionable power couple on London’s social scene. In Maria’s most famous painting (brought over to the London exhibition from the historic mansion of Chatsworth House), Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire as Cynthia, she portrays her aristocratic client in an inventive and much-copied dynamic pose. The artistic license of portraying her client as a moon goddess allowed Cosway to paint the duchess as if she were flying in diaphanous muslins through the night sky—imagery as over-the-top as today’s celebrity flowing gowns at Met Galas. And yet, all this artistic flair and pictorial skill were squashed by the fact that Richard Cosway would not allow Maria to sell her work. Richard was 20 years older than Maria, and not necessarily more talented but certainly with many more connections and, as a husband in 18th-century society, the one with the decision-making power. Maria shared her exasperation in a letter to her cousin: “Had Mr. C permitted me to paint professionally, I should have made a better painter but left to myself by degrees, instead of improving, I lost what I brought from Italy of my early studies.”

The Royal Academy explicitly barred from exhibition works that were “Needle-work, artificial Flowers, cut Paper, Shell-work, or any such baubles.” Watercolors, too, were dismissed as a lesser genre, while miniatures were relegated to a downstairs showroom and paintings of flowers by women routinely achieved lower prices or failed to sell. Victorian art critics praised beautiful paintings of wildflowers by sisters Martha (1824-1885) and Annie Mutrie (1826-1893) mainly because they were “images of nature” as opposed to artificial arrangements of hothouse bouquets. Such flower paintings were exhibited and praised, but they did not get the artists any closer to Academy membership.

Throughout the 19th century, British women artists continued to successfully exhibit and win prizes, with only the ultimate prize of Academy membership eluding them. A case in point is Elizabeth Butler (1846-1933), whose submission in 1874 of a historic painting called The Roll Call was hailed as a masterpiece. The Daily Telegraph praised it as “replete with vigour, with judgement, with skill, with expression and with pathos.” The painting depicting the quiet heroism of the Crimean War’s foot soldiers was purchased by Queen Victoria, and it was a prime example of a historical tableau—the art genre most prized and almost exclusively reserved for male artists. Butler’s skill at doing historical paintings and her stellar reputation led to her being nominated twice for Academy membership. Both times, she won the first voting round, but because the prospect of admitting a woman to the all-male membership was too alarming, she was then defeated. “Faith, we have had a narrow squeak!” openly proclaimed one of the voters. Thus, the entire 19th century passed without any British women artists crossing the barrier of Academy recognition, all the while winning critical accolades, gaining fame as watercolorists or genre painters, and exploring the new medium of photography.

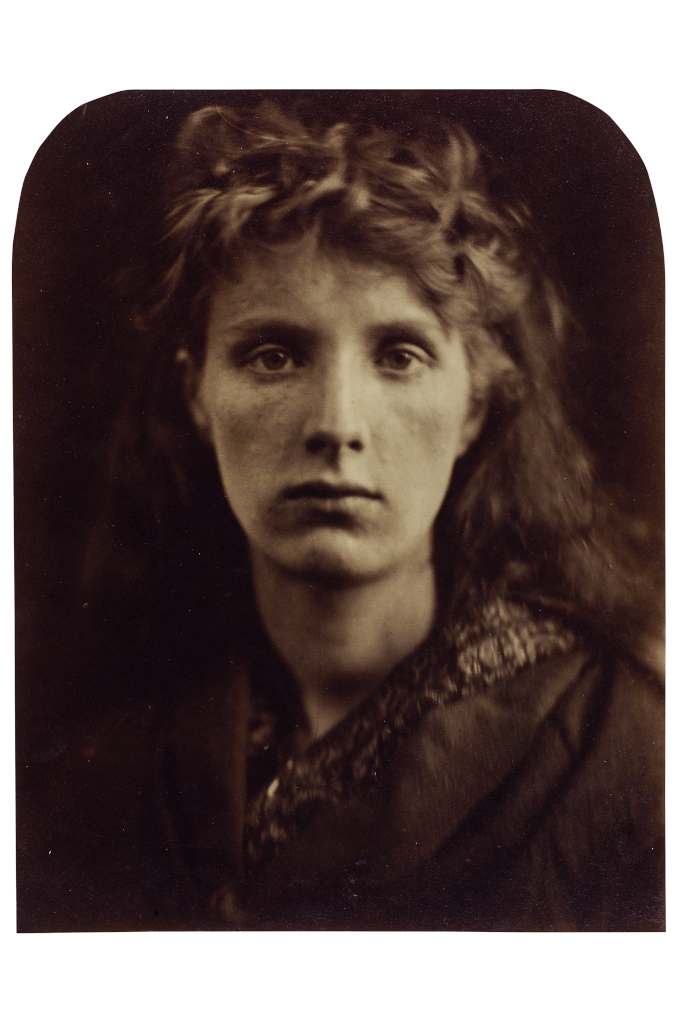

One of the most active photography pioneers was Julia Margaret Cameron, who did not even take up photography until she was 48 and was given a camera by her daughter. Within a dozen years, she had taken hundreds of portraits, participated in over 20 exhibitions, and pioneered artistic photography, inventing her own style of scene-staging, soft-focus, or leaving prints unretouched.

At the time when Cameron was devising her idiosyncratic style of photography, British art was dominated by the Pre-Raphaelite fashion of creating “historic” or “literary” scenes from Britain’s past. In this context, Cameron’s portraits were often brutally realistic—or conversely, very “cinematic and romantic.” Either way, these photographs were very different from the idealized and artificial-looking paintings of the late Victorians. Cameron was quite successful as a commercial photographer (for example, she took portraits of eminent English scientists and literary figures), but her contributions to the family finances proved insufficient after her husband’s colonial investments failed. His solution was to move his family all the way to Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka). Life in the colonies was indeed cheaper, but the move cut short Cameron’s career: she stopped taking photos or at least stopped having them commercially printed and sold.

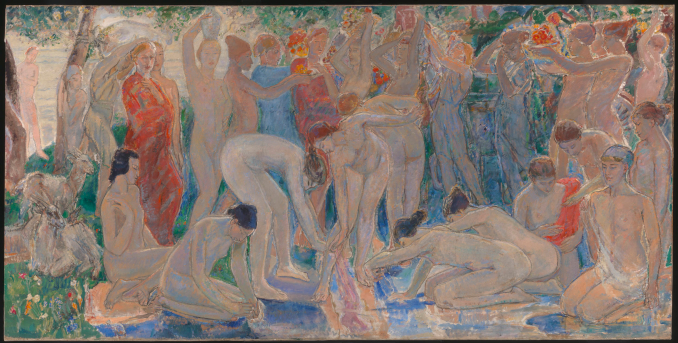

By the 1920s, things were getting better for women artists in Britain. WWI swept away a lot of the barriers facing women—they were called en masse to work, often in professions hitherto reserved for men, and in 1918, after decades of struggle, they were finally given the partial right to vote (they did not gain the same rights as men until 1928). In 1922, another milestone in women’s rights was reached when the Royal Academy admitted an artist named Annie Louisa Swynnerton (1844-1933). By that time, this neoclassical artist was nearing age 80 and the formal recognition came too late for her to succeed financially—she was quite bitter about it.

As post-WWI art moved on from Victorian realism or Academism, it was the Modernist style in its numerous subgenres that would dominate 20th-century art. By then, not only art but also women’s styles were changing at a dizzying pace. Victorian bustles and corsets were replaced by flapper dresses, and city streets were filling up with women riding bikes or walking unaccompanied. Women started driving cars and working with new technologies as typists and telephonists; some women operated heavy machinery in farming and in wartime industry. All of these rapid changes called for new looks of female models and new ways of portraying them. One of the leading artists of that period was Laura Knight, whose move from gray and rainy Yorkshire to an artist colony in Cornwall liberated her art. She started painting plein air scenes of contemporary women enjoying the beaches and cliffs. Her Dark Pool is one of the key paintings at the exhibition—an arresting image of a woman in a red dress standing on sea rocks. This woman is not looking at us; she is deep in her own thoughts, self-contained and independent. This image from 1917—toward the end of a war that changed everything, including the roles of women in society—closes the exhibition. Knight herself was admitted to full Royal Academy membership in 1936, and in 1965 she was given the first-ever solo retrospective at the Academy. It took these other British artists and their models 400 years to reach that point.

The exhibition at Tate Britain in London runs from May 16 through October 13, 2024.