Food for the Soul: The Art of Gold and the Gold in Art

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Unique, beautifully designed and crafted, and visually arresting, gold objects are always stars of any museum display, regardless of the symbolism or cultural context that may have been lost over time. From the earliest civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, through ancient Egypt, and in all African and South American cultures all the way through two millennia of European statehoods, gold has been used to create the most important works of art. One of the reasons that gold is so valuable in art is the fact that artworks made out of gold retain their shape for millennia—no other material, not even the hardest stone, can boast of that. The other reason is because of gold’s expense; in past eras, only the most accomplished artist would have been given commissions to make something out of gold, and only the clients with the deepest pockets, often rulers of nations, would have been able to commission objects of luxury or religious devotion. Some of the results include Cellini’s salt cellar, Chinese funerary masks, Egyptian figurines for pharaoh’s tombs, and Renaissance royal jewelry.

A great example of intricate detailing preserved thanks to the durability of gold are these earrings from the Getty Museum collection of Hellenistic artifacts. These earrings with tiny figures of Nike, the goddess of victory, have retained the miniature granulation around the discs and all the details of feathers on wings. Feathers and the torches (Nike’s typical attributes) would have been enhanced with enamel, and the discs would have had some gemstones or glass in the middle, but these details have been lost over the millennia. The design, however, down to the folds of the billowing drapes, has been preserved thanks to the characteristics of gold—a metal that does not oxidize like silver and does not rust like iron. This impermeability and an incredible shine have made gold the most desirable material for anything valuable, whether jewelry, ornaments, attributes of power, currency, or religious symbols.

R: Pre-Colombian standing figure, 100 BCE-100 CE. Gold. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Jan Mitchell and Sons Collection, Gift of Jan Mitchell, 1995. Photo: Open Access, The MET

Gold has an extraordinary malleability. You can stretch about 50 milligrams of gold into a thread 200 meters (219 yards) long or flatten it into a surface of 360 sq m (3875 sq ft). Thanks to its incredible durability, we are able to appreciate the skill and imagination of ancient craftsmen.

PRIAM’S TREASURE

Historians have either praised or vilified Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), a Prussian merchant who made his fortune in St. Petersburg and California, and who became a treasure hunter, discovering in 1873 one of the greatest gold treasures ever found. Obsessed since youth with Homer’s Iliad, Schliemann refused to believe this tale to be just literature, and he roamed the lands of ancient Greece in search of the real Troy. One of his early finds in Mycenae was a gold funerary mask that he dubbed the “Mask of Agamemnon.” When he finally dug in a hill at Hissarlik (modern Turkey), he declared the discovered layers of ancient city walls to be the ruins of the historic city of Troy, ruled in the 12th-century BC by King Priam. Later on, it turned out that the Hissarlik ruins contained as many as nine layers of city-states built and destroyed over four millennia.

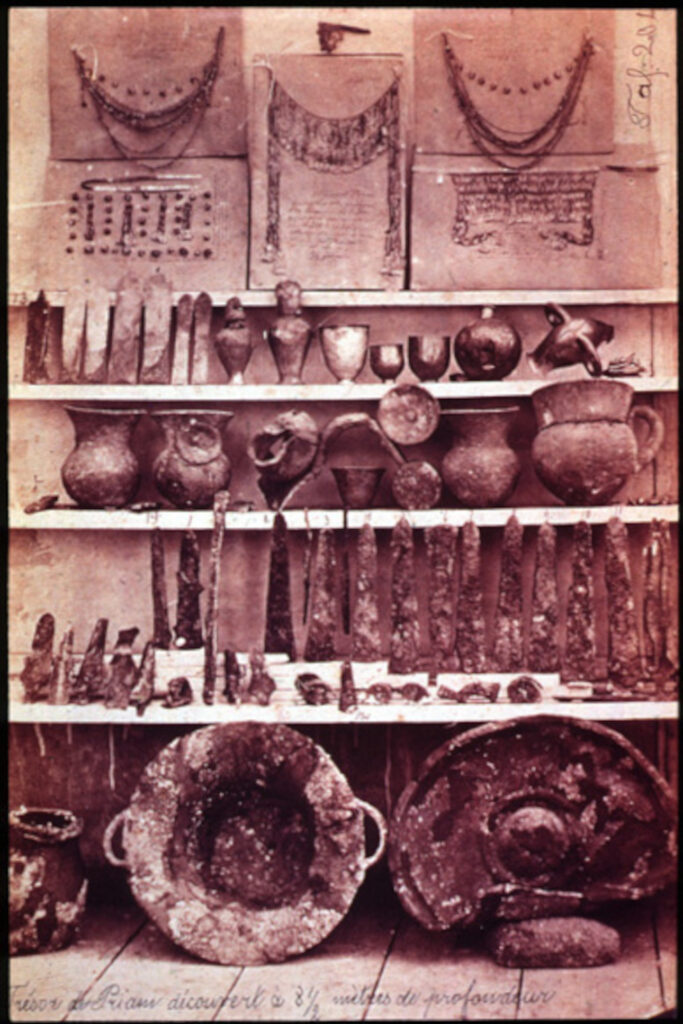

Schliemann’s faith in Homer and his hunting determination were rewarded when he unearthed a golden hoard, named by him “Priam’s Treasure,” which contained cups and beakers, headdresses made of chains, necklaces, earrings, and chalices—all of it made with great artistry from gold. He declared them to date back to the siege of Troy, though later research showed that they were from various earlier periods and not connected to the Hellenistic culture.

Schliemann’s contemporaries praised him for his fabulous discoveries and for becoming one of the stalwarts of the nascent field of archeology, but later scientists were unhappy about his destructive methods of extracting the objects and his cavalier treatment of the things that he found.

There is, for example, a famous photo of his wife Sophia, modeling one of the golden diadems and necklace from “Priam’s Treasure.” In the late 19th century, the idea of careful handling of 4000-year-old objects had not yet been born, even though already during Schliemann’s time he was criticized for mixing objects from different periods. In 1881, Schliemann donated the treasure to the German nation, and the golden objects were placed in the newly created Trojan Rooms at Berlin’s Ethnological Museum. Museum officials promised that “Priam’s Treasure” would be on public display for all time. Little did they know that all their curatorial care would come to naught when barbarians showed up at the gate. In May 1945, three crates containing the treasure of Troy were loaded onto a Red Army truck headed east, and for 50 years afterwards, the fate of the treasure was a mystery. In 1994, the collection emerged at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

The objects are now displayed quite openly at the Moscow museum in a special wing dedicated to Schliemann’s collection, with room after room of display cases identified as “acquired in 1945.” At the same time, the Neues Museum in Berlin displays nothing but empty glass cases in Schliemann’s Hall. There was a period when some copies of the originals were displayed, but during a visit to the museum this year, I found nothing but pitifully empty shelves. When I asked about them, I just got some polite smiles and “no comment.” It is unlikely that Schliemann’s pride and joy will ever return to the Berlin museum.

GOLD FOR GLORY

If you visit room 3 of the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, you will find yourself gazing at a display of glitter everywhere. Altarpieces depicting Madonnas and stories from the life of saints are all pictures painted on a gold background. Gold was used here as a sign of the utmost religious reverence and the images’ sacred nature. A medieval churchgoer expected to see something extraordinary when attending mass: soaring cathedral ceilings, gold altars glimmering in the candlelight, and halos of saints visible even in the dimmest light. In medieval art, gilding was everywhere.

Simone Martini and his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi were artists whose altarpiece for Siena’s cathedral—The Annunciation with the Saints Ansano and Massima—set the standard for how this religious event would be choreographed by later artists. Archangel Gabriel is on the left, having just landed with his robes and wings still fluttering, while a startled Mary recoils from this unworldly apparition. All this action takes place in a world illuminated by the gold background—literally made of gold. First, a wooden plank was covered with red clay and polished flat, and then it was covered with layers of gold flakes. Next, the surface was burnished with hematite to achieve the reddish sheen of gold. The pattern of the angel’s robe was made by scratching paint away to show the gilding underneath. Gabriel is shown announcing the words of God through letters that come out of his mouth, and the letters are all tooled in gold. To top it all off, the painting was placed in an intricate gold frame of Byzantine-style arches.

In medieval religious art, gold metal was part of the pictures—applied as gilding, embossed in patterns on clothes and halos, constructed as borders and frames around pictures in icons and altarpieces, incised as rays in the background, or sculpted into votive offerings. The metal that came out of Earth served as a symbol of divine superiority—a perfect link between the two realms.

MEDICI’S GOLDEN FRESCOES

By the Renaissance era, the icon-inspired, gold-grounded style of altar paintings had gone out of fashion. The new patrons—Italian bankers, German princes, and English nobles—wanted new images: mythological scenes, family portraits, and religious scenes that included their families as devoted donors. Although gold ground was no longer fashionable, there were other ways to include the precious metal in the pictures, especially if they were frescoes. A perfect example of the new use of gold is in Benozzo Gozzoli’s Procession of the Magi. The frescoes decorate a private chapel of the Medici palace in Florence and delight viewers with their details of sumptuous costumes, exotic animals, landscape vistas, and individualized figures—most of whom are Medici family members and other contemporaries of the artist.

In Gozzoli frescoes (and in many paintings of this period), the color of gold is achieved by applying a thick paste of gold flecks to accent elements of clothing, horse tackle, and the jewelry worn by various figures. These gold accents mixed in the colorful decorations are not very visible in electric light. However, if you are nice to your guide at the chapel, she might switch off the overhead lights for a moment, and then the magic appears: the ornaments, kings’ crowns, decorations on the horses’ tackle, gold thread in the clothing, and other “metal” elements of the frescoes start to glow in the dimmed light. These dabs of gold are actually made out of thick, gold-flecked impasto that shines through. The picture above shows the Procession of the Middle King, where the king figure represents Emperor John VIII Palaeologos, the penultimate ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire before the collapse of Constantinople. In bright electric light, you can see all the colors clearly, but when the light is dimmed, the elements that are the brightest are those golden specs accenting the frescoes:

The Medici gold is literally on the walls of their palace.

THE FIELD OF CLOTH OF GOLD

“Today the French

All clinquant, all in gold; like heathen gods,

Shone down the English; and to-morrow they

Made Britain India: every man that stood

Show’d like a mine. Their dwarfish pages were

As cherubins, all gilt: and Madams, too…”

~ William Shakespeare, Henry VIII

In the game of who has more power, a display of gold is a very useful yardstick. In 1520, two of the most powerful Renaissance rulers engaged in a game of one-upmanship during a summit meeting, which has come down in history as “The Field of Cloth of Gold.”

In the early 1500s, Europe was dominated by three young kings, all keen on establishing their position and success. The 19-year-old Charles V had just become the Holy Roman Emperor, the 25-year-old François I had been on the French throne since the age of 21, and the energetic King Henry VIII, 28 years old, had recently succeeded his cautious father on the throne of England. In 1518, Cardinal Thomas Woolsey negotiated a peace agreement called the Treaty of London, which (temporarily) put a stop to the numerous small wars that kept breaking out. Two years later, a meeting near Calais was called to ratify this non-aggression pact between the major rulers, but it was also an occasion to show off the youthful energy, strength, and success of both Henry VIII and François I.

The event was illustrated in numerous paintings, the most famous of which forms part of the British Royal Collection. The Field of the Cloth of Gold shows Henry VIII entering the compound of structures, which were in fact painted tents set on a brick foundation and supported by timbered framework. Just for the English side, over 6,000 craftsmen brought from all over England had labored to create these opulent if temporary abodes. The king’s entourage consisted of almost 4,000 people, including practically all of the English nobles and almost 3,000 horses—this parade of strength is shown on the left of the picture where the English king is attired in a golden cloak. His wardrobe also included tournament armor, which was described as decorated with 2,000 ounces (125 lbs /56.7 kg) of gold and over 1,000 pearls.

Meanwhile, the French had erected spectacular, gold-colored tents where the negotiations took place (this is what the title of this event is referring to). Contemporary chroniclers marveled at the amount of gold-threaded fabrics used for these tents. This extraordinary royal gathering lasted over two weeks, filled with secret negotiations, military parades, jousting contests, tournaments, and even the release of a dragon kite, perhaps filled with fireworks (shown top left of the picture). The magnificent display of wealth and power stoked many egos but did not secure a lasting peace. Barely a year later, all three superpowers were already back at war.

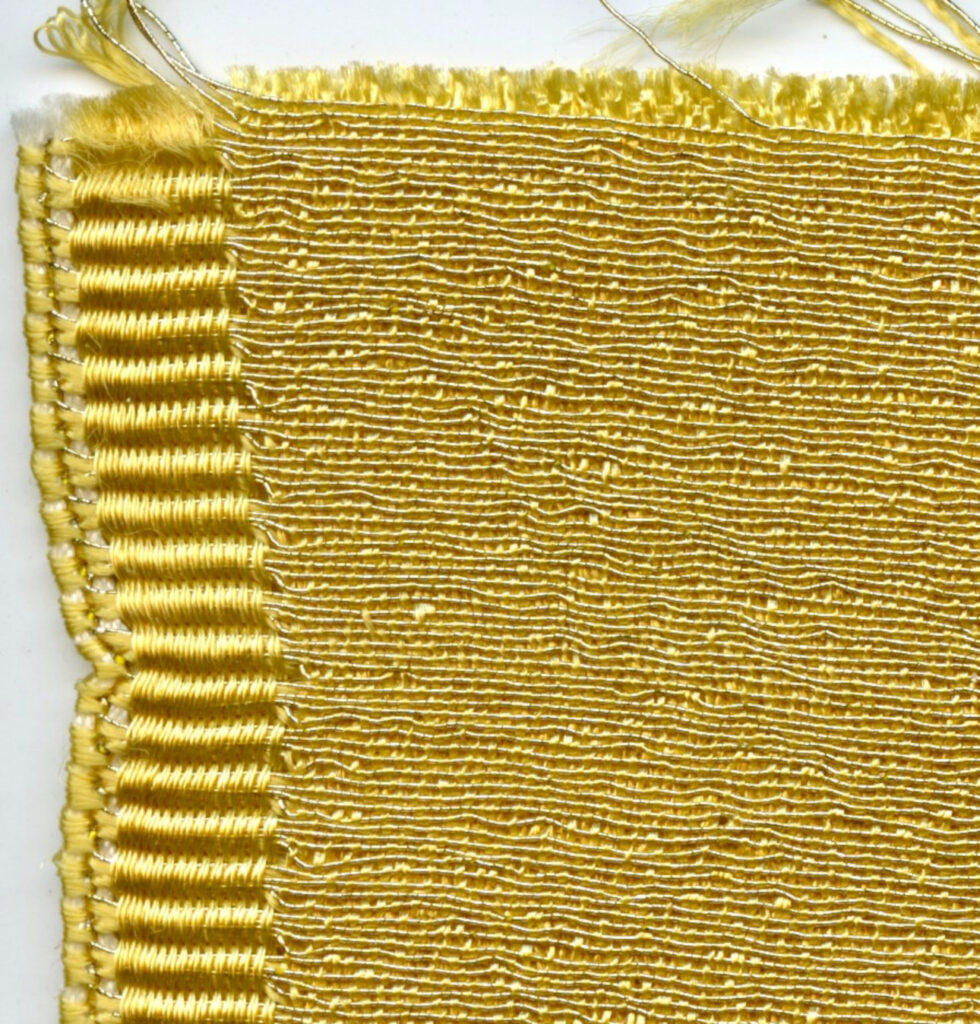

Cloth of gold is actually a type of textile where a yarn of silk or even linen is enveloped by a thinner thread of gold, or the threads alternate between metal and fabric. The resulting textile will be quite heavy, but it will glitter with undiminished luster. This epitome of luxury was described as far back as in ancient Mesopotamia, it was featured in the Greek myth of the Golden Fleece, it adorned the imperial clothing of Chinese rulers, and it was used lavishly by European kings. Henry VIII almost bankrupted the country preparing his red-carpet entrance onto the Field of Gold Cloth, and the court of French “Sun King” Louis XIV shone with golden robes at every occasion.

THE CELLINI SALTER’S AFFAIR

The year 1520, when the royal summit in the Field of Cloth of Gold took place, also marks in art the pinnacle of Renaissance perfection achieved by the grand trio of da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. All subsequent artists had to seek ways to transcend antiquity-inspired, ideally-proportioned figures and compositions in order to show something new and interesting. By the mid-1500s, art had entered a period later called Mannerism—a style of contorted gestures and poses, unusual angles or proportions, or clever hidden meanings or design surprises. Things became more complicated, and to attract royal patronage and lucrative commissions, the work had to be outstanding.

One of the Mannerist artists who worked for royal clients was Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), who described his adventurous life in a famous if much colorized autobiography that has retained its popularity over centuries, inspiring such works as a Broadway musical by Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill (The Firebrand of Florence), books by Agatha Christie, and even the Young Indiana Jones series. Any visitor to Florence would be familiar with Cellini’s virtuoso sculpture of Perseus with the head of Medusa, which graces the loggia at Piazza della Signorina.

Unfortunately, not many of Cellini’s drawings, sculptures, and jewelry works made it to our time, but one that is certainly the most famous is his salt cellar. Cellini made it in 1543 for François I (the same king who attended the Field of Cloth of Gold), and this table centerpiece is the only gold object by Cellini that has survived. Here is how Cellini himself described it: “The Sea, fashioned as a man, held a finely wrought ship which could hold enough salt. Beneath I had put four sea-horses and I had given the figure a trident. The Earth I fashioned as a fair woman, as graceful as I could do it. Beside her I placed a richly decorated temple to hold the pepper.” As Cellini told it, this ambitious project was in danger from the start; apparently, he was set upon by four bandits when carrying the gold from the king’s treasury, but he single-handedly chased them off. Whether or not the story of the vigorous defense of the king’s gold is true, the end result is extraordinarily beautiful.

In modern times, Cellini’s world-famous salt cellar has attracted lust not necessarily due to its beauty but rather due to the metal from which it was made. In 2003, the artwork—valued at about $60 million but really priceless—was stolen from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The thief turned out to be a 50-year-old security specialist named Robert Mang, who scaled the exterior wall, broke a window and the glass case, and absconded with the salter in 60 seconds. He was not deterred by the alarm system; he knew how ineffectual it would be in a theft that took less than a minute. In any case, he did not even need to hurry—after the alarm sounded, a security guard simply reset it, and the theft was not discovered until hours later. The police might have futilely been searching for a long time if not for Mang himself, who two years later demanded a ransom of $10M, all the while neglecting to hide his identity. The police traced him through a burner phone that he bought at a local store. Eventually, Mang led the police to a spot in the forest where he had buried the saliera in a box. This is where gold has an advantage over, say, paintings on canvas, because two years in wet ground did not damage the work. Cellini’s masterpiece is now back in the Vienna museum, with just a few scratches to attest to its adventures.

KLIMT’S GOLD PASSION

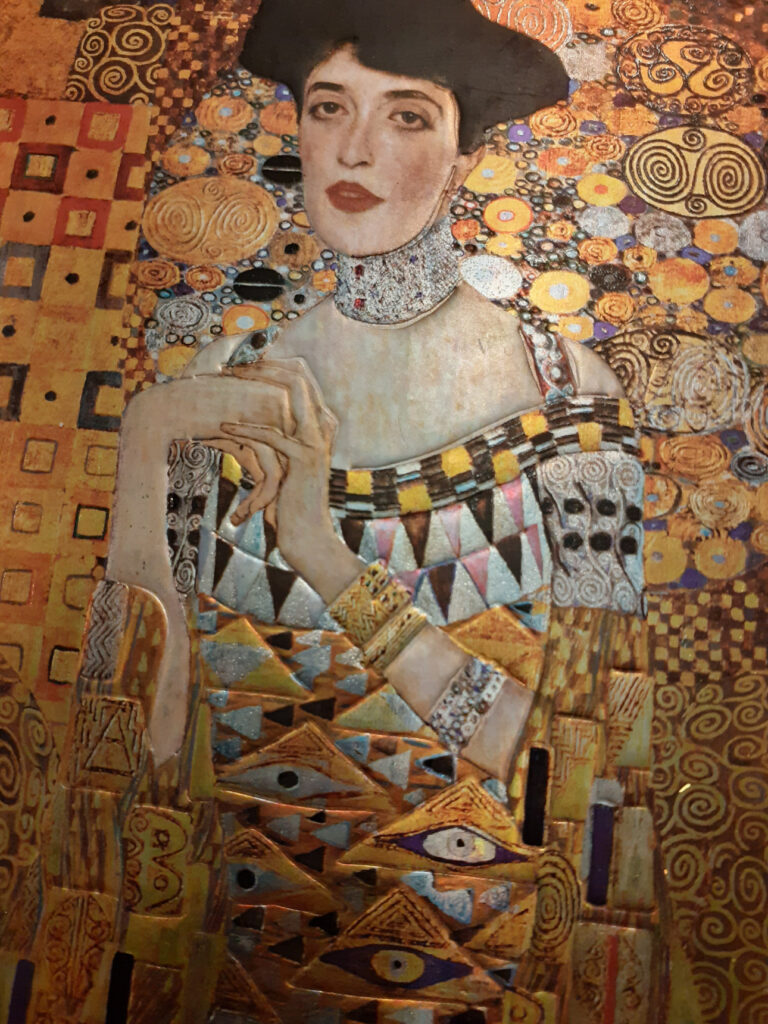

If we are looking at art in Vienna, it is hard to ignore its most famous painter, Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), and his obsession with gold ornamentation. For centuries, gold had served to underscore religious importance—in the devotional paintings of the late Gothic period, in the gilding of church decorations (especially in Baroque altars and architectural elements), and in religious objects such as crosses, chalices, and ornaments. By the time Klimt came around, however, gold was no longer solely in service to religious adoration and respect for God-anointed royalty; artists could use gold to express emotions and especially lust—both sexual and financial—but perhaps also to communicate messages of triumph, domination, or superiority. For Klimt, it meant that he could use the oldest techniques of mosaic, gold leaf, embossing, and jewel incrustation to create pictures that pioneered the modern art ideas of mixed media, collage, and image manipulation.

Out of all the “Golden Phase” pictures that Klimt created at the turn of the 20th century, the final, most complex, and most famous was his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of a Viennese “sugar baron.” In this painting, Adele’s face is fairly naturalistic, painted with glowing pink skin, and we can admire her long elegant hands, but the rest of her attire melds into interlocking gold and silver tiles, swirling ornaments, and a gold background. Klimt may have revived the old Byzantine mosaics in this picture, but this is not a religious decoration; it is a portrait of a contemporary citizen of Vienna, a woman whose wealth and social status are signaled by the gold that envelops her. In a picture adorned with gold and silver leaf—very thin layers of metal—she is literally bathing in gold.

Apart from being one of the most recognizable and complex works of 20th-century art, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer has a dramatic story and represents a milestone in the history of Nazi-era looting and subsequent attempts at recovery. Hitler’s government seized the picture in 1941; after the war, the picture was displayed at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna. In 1999, Maria Altmann, an elderly descendant of the family, started a restitution claim, which dragged on for seven years. The fascinating story of Altmann’s attempts to win back her inheritance is presented in the brilliant movie Woman in Gold, starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds.

In real life, gold can be the source of both great happiness and great misery, sometimes at the same time. That fact is metaphorically presented in the myth of Midas, a king whose wish to have anything he touched turn into gold was granted by Zeus with disastrous consequences. The greedy king, unable to feed himself anymore, pleaded with the gods to relieve him of the blessing that had turned into a curse. His wish granted, he was finally able to wash all the gold off his body in the river Pactolus. This mythological scene is the subject of a haunting picture by Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), a French Baroque painter renowned for his mythological and historical tableaux. In Poussin’s picture the exhausted king Midas is resting by the river, gold still clinging to his sandals, while his attendant is examining the gold flecks that fell off, looking at them with disbelief and wonder.

In art, gold generates mostly happiness, aiding in the creation of beautiful pictures, jewelry, statuettes, and other artifacts that retain their shape for a long time. Sometimes gold expresses celestial connections, sometimes is a symbol of erotic energy, and sometimes it is simply the best conduit for the eye-catching shine we tend to like in valuable objects.