Food for the Soul: The Art of Reinvention – Tamara de Lempicka

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

When in 1916 Tamara married Tadeusz Lempicki (pronounced “Wem-pitski”), a Polish nobleman and a lawyer appointed at the Russian Imperial Court in St. Petersburg, it seemed that her future was on a settled course. She would be the beautiful wife of a handsome lawyer and raise her newborn daughter Marie Christine, nicknamed Kizette, in the safety and luxury of the high-society household of her aunt, who was married to a St. Petersburg banker.

This dream wedding took place less than a year before the Russian empire collapsed in the firestorm of the Russian Revolution. Tamara with baby Kizette fled to Paris; Tadeusz was arrested by the revolutionaries. Tamara used all her resources, financial and social, to extricate Tadeusz from the clutches of the Czeka (Soviet secret police) and, unlike so many other families of men arrested by the new Soviet rulers, succeeded in getting her husband out. However, the life they both knew was gone—their wealth and social position were erased together with the Russian empire, and they became impoverished emigrants, like so many Polish people in centuries past. Tadeusz could not find his way in these new circumstances.

Paris: A Good Place for Reinvention

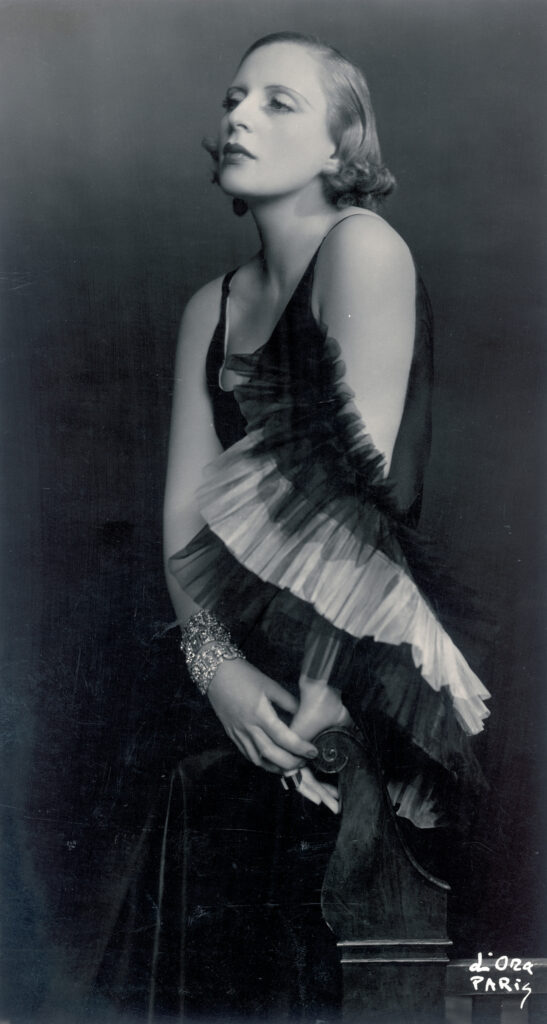

Tamara de Lempicka (1894-1980), a society woman who had never needed work skills or a profession before, knew that she would have to find a way to make a living, and she decided to reinvent herself as a Parisian artist. She started by convincing two Parisian teachers to take her on as their student: André Lhote, who was a master of drawing, and Maurice Denis, an artist who decorated the residences of rich patrons in the new Symbolist and Modernist styles. She soon surpassed them both—her drawings were more accomplished than Lhote’s, and her decorating prowess got her numerous society clients who hired her for interior design. In the fashionable Paris society of the 1920s, Lempicka was known for her Greta Garbo icy blonde looks, her impeccable taste, her connections to Italian and Russian aristocracy, and her string of celebrity lovers and admirers. She painted them all. She also used her angel-faced daughter as a model, even if she left the actual childcare to nannies and family.

Among mutual infidelities and diverging lifestyles, Tamara’s marriage crumbled. Tadeusz reluctantly took on a job at her uncle’s bank and started spending more time in Poland; Tamara remained in Paris, embracing a bohemian life full of romances with both men and women, who all became her models. All that remained of her marriage was her artistic signature “de Lempicka” (now preceded by “de” to denote the nobility title) and an unfinished portrait where she left unpainted her husband’s right hand (the one that wears a wedding band).

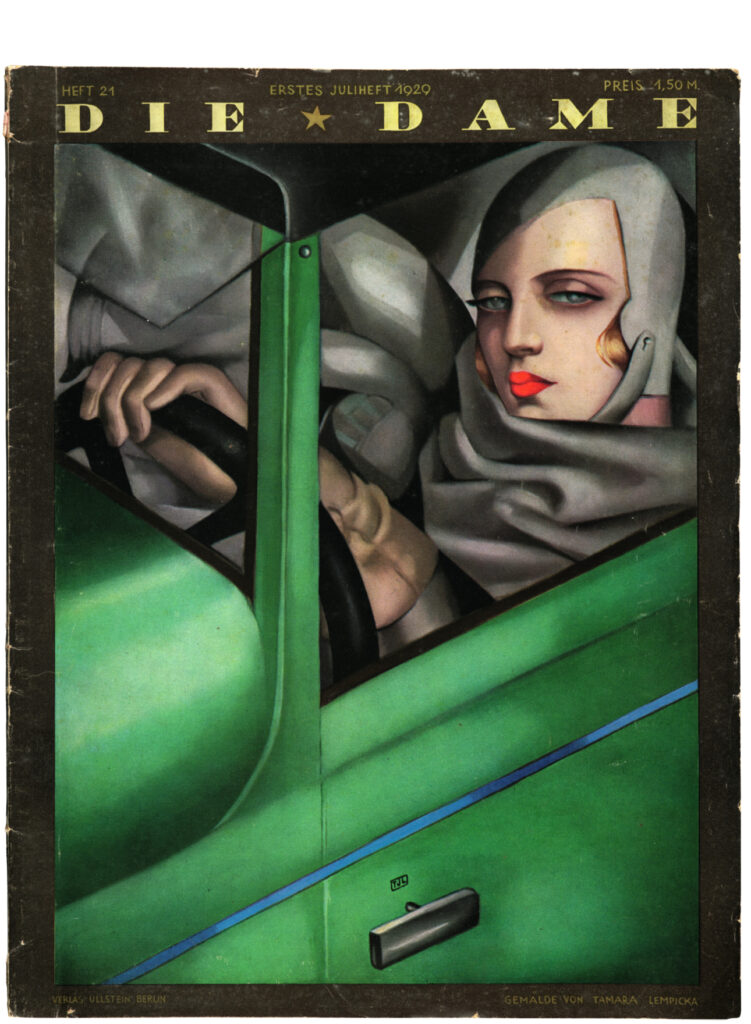

As she began exhibiting all over Europe, she also started a collaboration with the German fashion magazine Die Dame. Some of her most iconic artworks started out as paintings for covers of this magazine. The most famous was her self-portrait titled Tamara in a Green Bugatti—a painting that is now in a private collection but which had countless reproductions published whenever Art Deco style was mentioned.

The Apogee

Tamara’s mission to reinvent herself as a leading Parisian artist was a success and, against all odds, she did. Her paintings found ways to important exhibitions and galleries, alongside such new artists active in Paris at the time as Picasso and Kandinsky.

By 1925, Lempicka’s style was so characteristic that her pictures became an embodiment of Art Deco—precise lines, sculpted hair, slightly inflated but sinuous shapes of bodies, fabric that flowed in Renaissance style folds, everywhere vivid colors, and above all, sharp lines and precise contours. Lempicka hated Impressionism: “Among the hundred paintings, you could recognize mine…and the galleries began to put me in the best rooms, always in the center, because my painting attracted people. It was neat; it was finished.” She abhorred the fuzzy lines, rapid strokes, and pixilated blobs of color that were the cornerstone of Impressionism.

If you look closely at the girl in her Young Girl in Green, the model’s neck is painted as two sides of a beige pyramid, and every lock of hair looks like a wood shaving but hardly like a strand of hair. Lempicka was not going for either an impression or a realistic image, the former being an outdated art style and the latter being inferior to photography. She was borrowing the sharp angles from Cubism, but she was not interested in deconstruction. She was always going for Style with a capital “S”—her own vision of what modern people should look like. Her painting style is indeed always recognizable from afar: a vivid-hued composition of sharp angles and soft, precisely painted bodies or folds of fabric.

In her youth, Tamara had traveled with her grandmother on tours of Italy and France, and the future artist fell in love with Bronzino, Pontormo, and Ingres. She adored the clean colors and smooth lines of the Italian Renaissance portraits and the sensuality of Ingres’ odalisques, so their art guided her pictures as well. Of course, Lempicka’s style was not hers alone—the whole Art Deco look from about 1910 onward was characterized by bulky geometric forms and bright colors. It was a design that would alternate stepping stones and cubes with rounded corners, reduce human bodies and animal or plant shapes to stylized forms, and use industrial-inspired, simplified lines for cars, houses, or household items. Art Deco (the actual term became popular decades later) was a reaction against the fuss of Victorian excess of decoration. Everything that the post-WWI lifestyle introduced—from flapper dresses to Bauhaus buildings—was the style that Lempicka embraced and expressed in her art.

By the mid-1930s, de Lempicka was remarried to Baron Kuffner, a wealthy and titled Hungarian landowner, and her paintings participated in important shows all over Europe. The 1930s were a period of great artistic productivity amid a torrent of social engagements, but the winds of change had started to blow. The Great Depression cut down on orders from wealthy patrons, while tastes veered away from the chiseled looks of Art Deco. Although Lempicka was less affected than many other Parisian artists—she was married to a wealthy socialite, her paintings were exhibited, and she was able to expand her repertoire from portraying wealthy clients to genre pictures such as religious themes or still lifes—things were not well in the Europe of the late 1930s. Tamara, a refugee from the Russian Revolution, could read the signs early on. For a couple of years before Hitler attacked Poland, she was already pressuring Kuffner to sell off all his lands and emigrate across the ocean. He resisted at first, but he could read the ominous signs as well.

The arrival of WWII put a crashing stop to the lives of all Europeans; the difference was that Tamara anticipated the catastrophe. She even managed to arrange for Kizette to leave Poland in August 1939, and by the time the Germans marched on Paris, the family was already in New York—émigrés again.

The Price of Emigration

It’s a cliché that war changes everything, but it was true in the case of Tamara de Lempicka. Her art was luminous and original before the war, but it never revived after the emigration and separation from the source of her artistic strength—the Paris bohemia of the jazz years. After escaping Russia during the 1917 Revolution and leaving Paris on the eve of the German invasion in 1940, Tamara had to start again in the U.S. She was a woman without a country—a perennial émigré.

The tragedy of Lempicka’s biography is that she failed at that last reinvention. She was artistically active throughout the 1940s, exhibiting and painting, first in New York, then in California, and, after the war, again in Europe. The exhibitions did not stop, but Lempicka’s popularity waned—her characteristic 1930s style was not in step with post-war art movements. Over the next decade, Kuffner’s finances started to ebb away (his ancestral lands in Hungary were nationalized), and Tamara’s new paintings could not support their lavish spending. Baron Kuffner died suddenly in 1961. For the next 19 years, Tamara’s work was sporadically exhibited while the artist herself traveled between Los Angeles, Paris, and Mexico, where she eventually settled. It was the fourth country where she tried to reinvent herself. However, the heyday of her successes in 1930s Paris could not be replicated in the New World. In America of the 1970s, the aging Grande Dame of Art Deco, the eccentric Baroness Kuffner, the four-time émigré was practically forgotten.

The Legacy

Until the mid-1980s, Tamara de Lempicka was not a household name in art, except in her native Poland, where even schoolkids were familiar with her paintings. In the last 30 years, thanks to the efforts of her descendants, art historians, feminist writers, and fans of Art Deco style, her paintings have become quite iconic, especially in Europe—but Lempicka’s art has still not gained a widespread following in the U.S. This may change after a historic exhibition in San Francisco, which is the first scholarly retrospective of Lempicka’s art in the United States. The exhibition, entitled Tamara de Lempicka, presents 150 works and photographs. It is currently on display at the de Young Museum of Fine Arts in San Francisco (October 12, 2024 – February 9, 2025) and will continue on to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston (March 9 – May 26, 2025).