Food for the Soul: The Year in Art

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Throughout the year we celebrate various holidays—some religious, others cultural or connected to historical events. I thought it might be fun to find art that would illustrate those calendar milestones. In some cases, I have researched artworks that are not well known because they are not on display, even if they are part of major museum collections. Others may be less known because their creators were not very popular, even in their home countries.

Let’s imagine a 2025 arts calendar by Food for the Soul:

January

The Pre-Raphaelite movement appeared in mid-19th-century England as a reaction against the Victorian aesthetic of either celebrating neoclassical historical tableaux or flooding the market with the kitschy genre scenes so beloved by the newly forming bourgeoisie. Poets like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, painters like John Everett Millais, and critics like Frederic George Stephens established the principles of a new style that focused on painting supremely realistic and beautiful images—often referencing the medieval history of England, Biblical tales, Shakespeare, Dante, or famous poems—while seeking authenticity of costumes and landscape. The second wave of artists that came a couple of decades later included designers like William Morris. Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) was Morris’s founding partner in his textile company, and he later led the development of a style called the New Aesthetic, which continued the focus on the beauty of design. The tapestry titled The Adoration of the Magi was designed by Burne-Jones in 1888 with Morris’s input, and it is a perfect example of the marriage between the Pre-Raphaelite style and the new achievements in textile design, an area of craft reviewed by Morris’s company.

February

The Kiss by Francesco Hayez (1791-1882) is one of the most popular images in Italy. At the Brera gallery in Milan, there is always a small crowd of Italian visitors who take a picture of this painting. Francesco Hayez, who came from a modest family in Venice, attained through his talent and long career the directorship of the Pinacoteca di Brera and a position as one of the most prominent Italian painters of the 19th century. While the theme of this painting—the passionate embrace of two lovers—is obvious in this realistic scene, for Italians, this picture (first shown to the public during the period of intense struggle for national independence) also carried a symbolic meaning of the alliance between France and Italy—the two nations allied during the Italian wars of independence.

March

In many countries, March 8 is earmarked for International Women’s Day, a celebration of women’s lives and rights. It was first established as a holiday in 1911 in Central Europe and then gained wider recognition in the 1970s when it was recognized by the United Nations. Even though it was originally tied to socialist movements, the women’s suffrage fight, and labor union activities, in the current century the holiday is more about women’s rights and potential. It is often also tied to political actions in favor of equal pay and social opportunities, or as a day to commemorate the struggle to protect women from physical and economic abuse. In the U.S., this is not a popular holiday, especially given that it has been commercialized by some corporations, but in Europe it remains a day to celebrate women’s roles in society.

In celebration of International Women’s Day, here is a portrait of a painter who earned a living as an artist in prerevolutionary France, when few women had opportunities for intellectual professions. Three years after this was painted, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803) was admitted to the French Royal Academy, but a mere six years later the French Revolution had wiped out the royals, her aristocratic pupils, and the guild. When the academy was reestablished in 1793, women were excluded as members.

April

Spring is the time of biological rebirth, as well as warmer and longer days and a renewed energy. It is celebrated in the religious holidays of Easter and Passover, but in Japan and China, it is also celebrated in a much simpler way as a renewed opportunity to enjoy nature. This classic Japanese woodblock print shows court women wandering around cherry trees in bloom.

May

Breakfast in Bed belongs to the most famous category of Mary Cassatt’s paintings, the ones where she portrays relationships between women—mothers, grandmothers, aunts, and nannies—and their small charges. The reason these pictures have such an enduring emotional impact is that they often capture intimate moments between a woman and a child—moments that would rarely have been observed by male painters, whose approach to portraiture was usually more formal. Here, we have a moment at the start of a day. The toddler is enjoying the treat of eating in bed, while the mother has barely opened her eyes. The most endearing is the expression on the young mother’s face—she is still half asleep, enjoying the warmth of her bed and the closeness of the child that she holds in the protective loop of her arms.

June

One of best museums in London, the National Portrait Gallery, has this painting modestly tucked in a corner of one of its great halls. Painted in England around 1776, the year when Britain lost its American colony, it is an unusual picture. In portraiture, it was the period dominated by formal pictures commissioned for grand residences. Men would be shown with their spouses (to show off their successful domesticity), perhaps with their hunting rifles, their dogs, and horses (to show them in a typical landowner milieu) or perhaps in a battle scene (to show their bravery and importance). This is a picture that shows Christopher Anstay, a landowner and a poet, in a playful moment with his eldest daughter Mary Ann, who is waving a doll. This doll is actually a fashion doll wearing a miniature version of the dress that Paris dressmakers would send to their foreign clients to solicit orders. Anstay is shown engaged in an intellectual activity (i.e. writing a poem), but it says something good about him as a father that he also agreed to be painted in a playful interaction with his daughter.

July

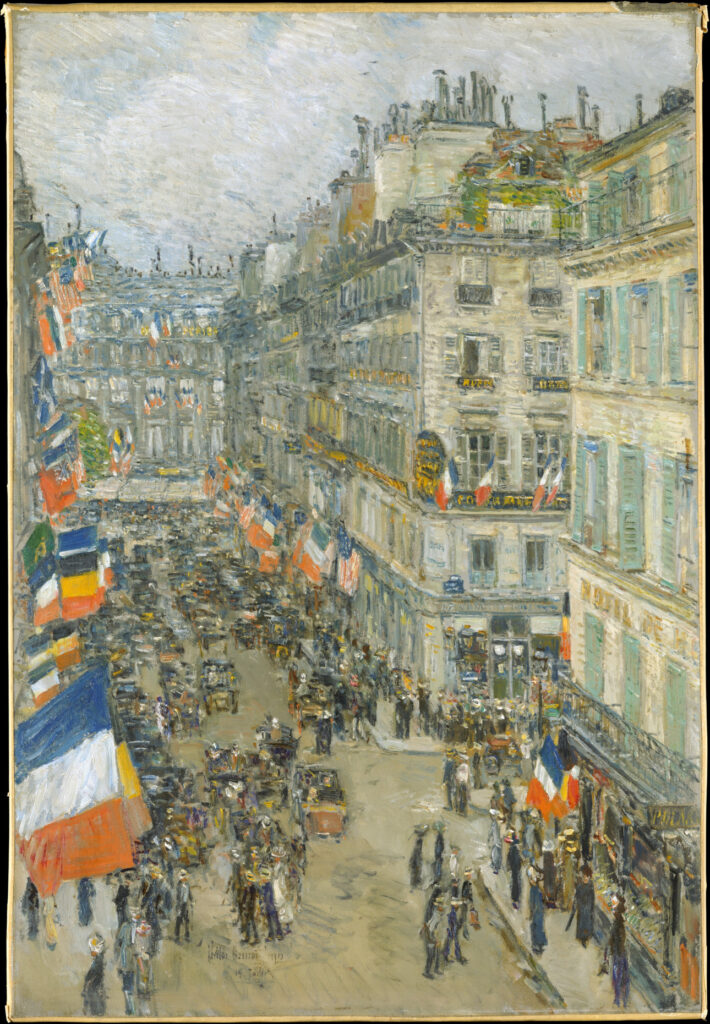

In many countries, such as the U.S. and France, as well as in numerous South American nations, July is the month dedicated to a national holiday. The granddaddy of these July celebrations is probably France, where the 14th of July commemorates taking down the Bastille prison and the start of the French Revolution. On this date, a national fête takes place all over France, and it includes patriotic parades in town centers as well as holiday parties at local restaurants. Streets are festooned with flags hanging from balconies.

Impressionism as a style was born in France, but eventually it penetrated other countries, usually through artists who traveled to Paris to study. One such artist was the American Childe Hassam (1859-1935), a Maine native and long-time New Yorker. During Hassam’s visit to Paris in 1910, he painted a Bastille Day celebration in a street he could see from his hotel balcony. He painted in some American flags, which perhaps were not so much in evidence at the French holiday but would possibly have reminded him of the 4th of July holiday back home. In fact, the flag-festooned street would become an important theme in paintings he would create a few years later, during and after WWI. Hassam is very famous for his series of paintings of flag-adorned streets of New York.

August

Let’s go to the beach!

Spanish Impressionist Joaquin Sorolla (1863-1923) has often been dubbed as a “master of light” in reference to his famous beach scenes like the one above. The foreground is taken up by several figures—children playing at the water’s edge and a woman swathed in white against the strong sunshine. As if all this activity and the frothy waves were not enough to provide visual interest, the background is all taken by enormous cream-colored sails that spread like a gigantic bird. This whole busy but carefully composed scene is bathed in the blinding light of a Mediterranean summer. You can almost feel the rising heat on this beach in Sorolla’s native town of Valencia.

September

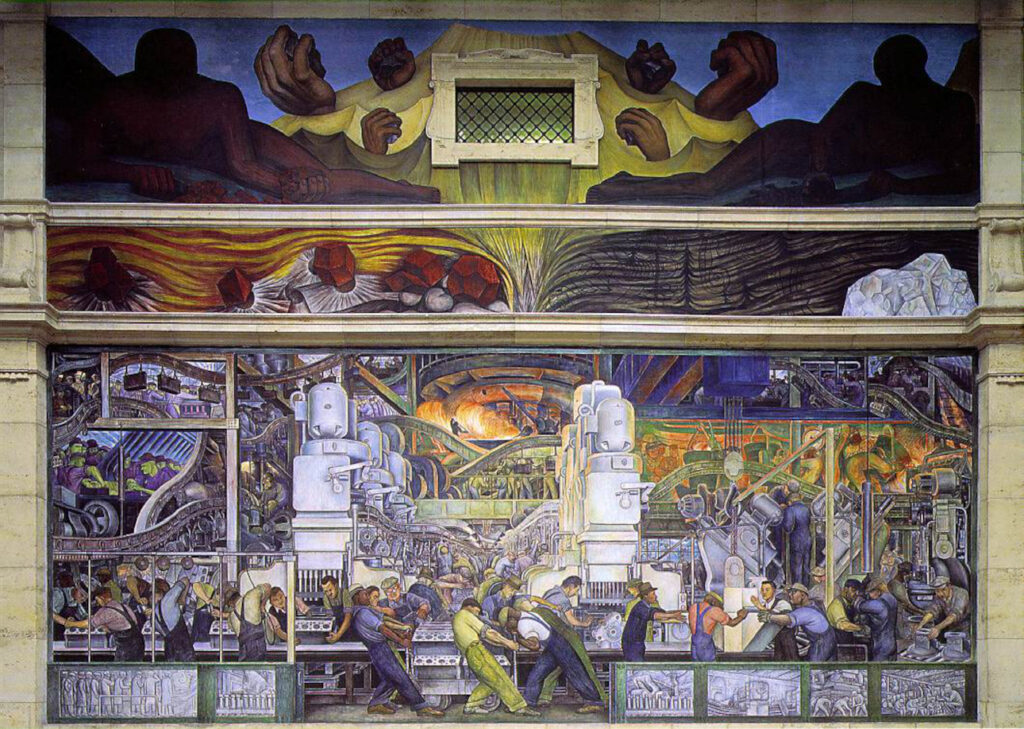

The September holiday called Labor Day is known only in the U.S. and Canada. European workers traditionally celebrate on May 1. Thus, it is only fitting that the celebration of working people for September should be illustrated by a fresco from the U.S. heartland. Diego Rivera (1886-1957) painted his mural titled Detroit Industry on the walls of the Detroit Institute of the Arts. In 1932 when Rivera arrived in Detroit, it was the third year of the Great Depression. Both capitalism and communism were turning out to be societal failures, and the hopes stirred by the Mexican Revolution in Rivera’s native land were declining. Rivera placed his new ideological hopes in technology and the power of machines. He got a commission to create a series of panels that would illustrate all types of industry in Detroit, with the car industry being of course the leader, since it powered the town and Henry Ford was bankrolling the mural’s production. Rivera spent weeks observing assembly lines at automotive, chemical, and pharmaceutical plants. The resulting murals were an amalgam of industrial images such as metal stamping or welding, with figurative pictures of scientists in labs, workers at assembly lines, and designers with blueprints—the world powered by science and technology. In the early 1930s, it was still possible to believe in machines as agents of good; soon after, the arming up prior to WWII had wiped out the illusion. Rivera returned to Mexico after four years of painting murals, and he turned toward easel painting—mostly commissioned portraits of rich clients, as well as some his best-ever canvases of peasants, often carrying his trademark calla lilies.

October

Artur Leon Gąssowski (1841-1911) is a painter who is practically unknown both in his native Poland and in France, where he spent most of his life. His Mountain Landscape with Sheep was painted in the picturesque regions of southwestern France. Not only is this a beautiful composition from the point of view of the artist looking down onto the vista of a mountainous path, but it is also a delicate image of a very short moment. Gąssowski captured the rising of the morning fog that would eventually dissipate in the sunshine. The sky is greyish, and the trees on the left are already reddening. This is a season of golden autumn, soon to change into the leafless season of late fall, when the morning fog will not be so delicate and there will be little of this sun that casts long morning shadows. This is the weather of October, which before long will change into the cold and wet days of November.

November

When Dutch republic artists like Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-1683 or ’84) were painting their sumptuous arrangements of food-laden tables, these beautiful pictures were not meant to be just a decoration. They would contain moralistic messages about the impermanence of worldly pleasures, filled with symbols of faith. They were, of course, also a beautiful adornment for any grand house—large canvases filled with realistic images of ripe fruit on silver platters, precious Ming porcelain, exotic shells, and colorful butterflies. Several hundred years later, we have mostly forgotten the key to decode all the symbolism of these peeled lemons, bulbous violas, and wine glasses precariously tottering on the edge of tables. Instead, we can just savor the abundance of juicy fruit, the gleam of silver dishes, and the complex arrangement of all these objects—from scrunched fabrics to a nautilus shell ewer. Matisse was so fascinated by this composition (de Heem’s first and probably the best of the series) that he made his own, modern version of this arrangement. Matisse’s painting Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s “La Desserte” is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

December

This particular painting by Claude Monet (1840-1926) was quite controversial when he painted it in 1868. Monet’s patron offered him, his then-girlfriend Camille, and their newborn son a prolonged stay near a picturesque area of Étretat on the Normandy coast. There, Monet painted his famous views of the arched rock, and in winter he would paint snowscapes. This painting was spurned by the general public and the Salon judges. Parisian art critic Félix Fénéon described this disfavor in these words: “(The public) accustomed to the tarry sauces cooked up by the chefs of art schools and academies, was flabbergasted by this pale painting.” At the time, when the Impressionists were barely starting their exploration of outdoor light and color, shadows in paintings would be represented in varying degrees of darkness. Artists working outdoors like Monet were observing that shadows are actually colored, depending on sunlight falling on surfaces, especially white ones like snow. This is what is happening in The Magpie–– the color of the shadow on the snowbanks is bluish and not black.