Food for the Soul: Matisse’s Windows

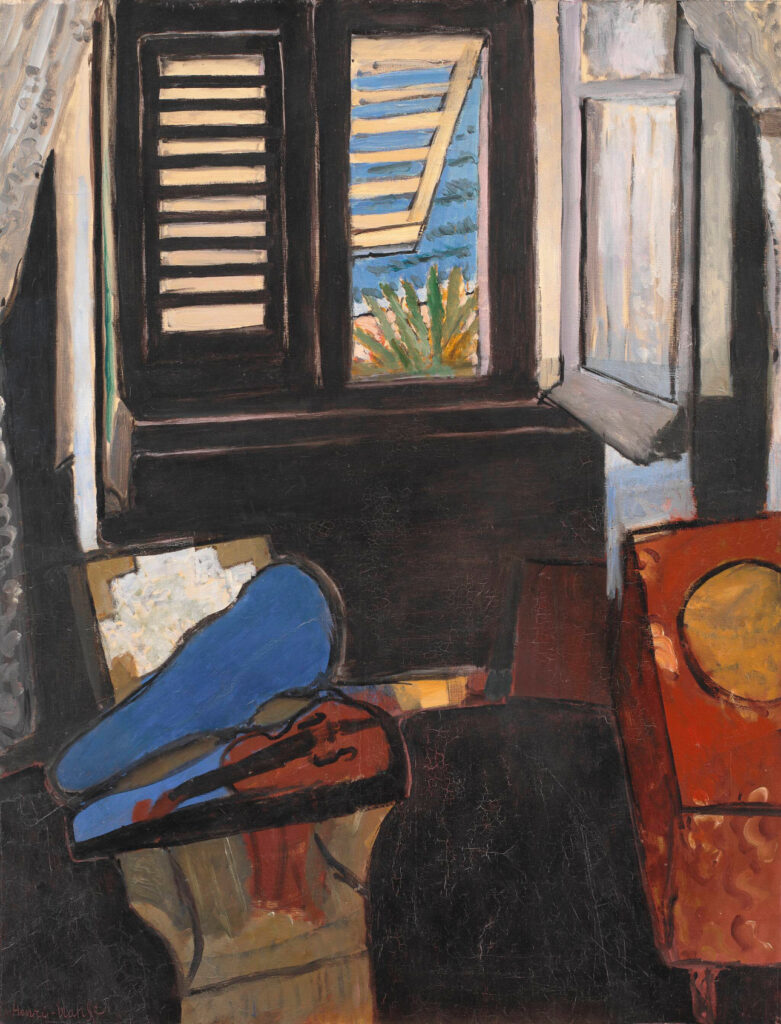

Henri Matisse. Interior with Violin, 1918. Oil on canvas. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“Windows have always interested me because they are a passageway between the exterior and the interior.”

~ Henri Matisse

January 1, 2025 marked the day when images of Henri Matisse’s paintings moved into the public domain. This means that some of his most iconic images will end up on T-shirts and lunch boxes, but it also means that I can present to you some of his most alluring paintings on the theme of a window view. Matisse painted them for decades, as soon as he found his stride among the numerous styles that emerged at the turn of the 20th century—Symbolism, Divisionism, Syncretism, Cubism, and many other “isms”—that inspired him or, conversely, got him riled.

In 1905, Matisse was a debutant painter, quite poor but determined to make his living as an artist. He would spend summers painting in a Mediterranean fishing village called Collioure with a couple of friends, one of them being André Derain. Open Window, Collioure comes from that summer’s painting session. The interior and the exterior are differentiated by types of brushstrokes (the inside is painted by large smooth strokes; the outside is rendered through short sharp dabs), but the two are unified by a romantic, joyful color scheme: peach pinks, viridian green, and lavender accents on the boats and flower pots. There are no shadows, and interior and exterior merge into one. It was the unrestrained use of vivid, “non-naturalistic” colors that earned Matisse and Derain the moniker of Fauvists (“wild beasts”).

Before WWI, Matisse’s most important clients were two Russian merchants, Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, who both commissioned specific paintings and decorations from the artist, invited him to Moscow, and paid for his travels. Morozov also sponsored Matisse’s travel to Morocco in 1912, ordering from him a couple of landscapes and a still life, following on his previous purchases of half a dozen pictures. Matisse took his time, but when he finally delivered the paintings to his client, they were masterpieces. The Moroccan Triptych shows morning, noon, and evening in Tangiers, each of them having elements of all three genres—a landscape, a portrait, and a still life—unified by the location and the seductive shades of ultramarine and turquoise blue. The evening picture, Window in Tangier, was a view from a window onto the city enveloped by afternoon shadows. The border between interior and exterior is marked with a couple of vases, but they sit on the windowsill in the same shade of blue as parts of the city shadows. The entire painting and the remaining two images of the triptych are a study in numerous shades of beautiful blues, with landscape elements painted as a series of geometrical shapes.

A couple of years later, Matisse had his brush with Abstractionism. He actually painted two versions of View of Notre Dame from his studio at Quai St. Michel. One was a more traditional city view of the cathedral, whereas the one shown above would probably not be recognized as a view of a building if not for the title. Everything here is just a symbol of a place rather than an actual landscape element. The greenery along the riverbank is marked with a green blob, the cathedral towers are two rectangles, and Petit Pont is marked as a semi-arch. It is a very dynamic composition that can be viewed as either a simplified cityscape or a pure abstraction. The colors of this painting, created in 1914, are subdued and very different from the previous years’ exuberant Fauvist colors. The year 1914 marked the beginning of WWI, and Matisse—with part of his family behind enemy lines and himself stuck in a Paris apartment—poured his wartime worries into his art. This painting was in a private collection until the 1960s when it was exhibited in Los Angeles, inspiring such American abstractionists as Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Motherwell.

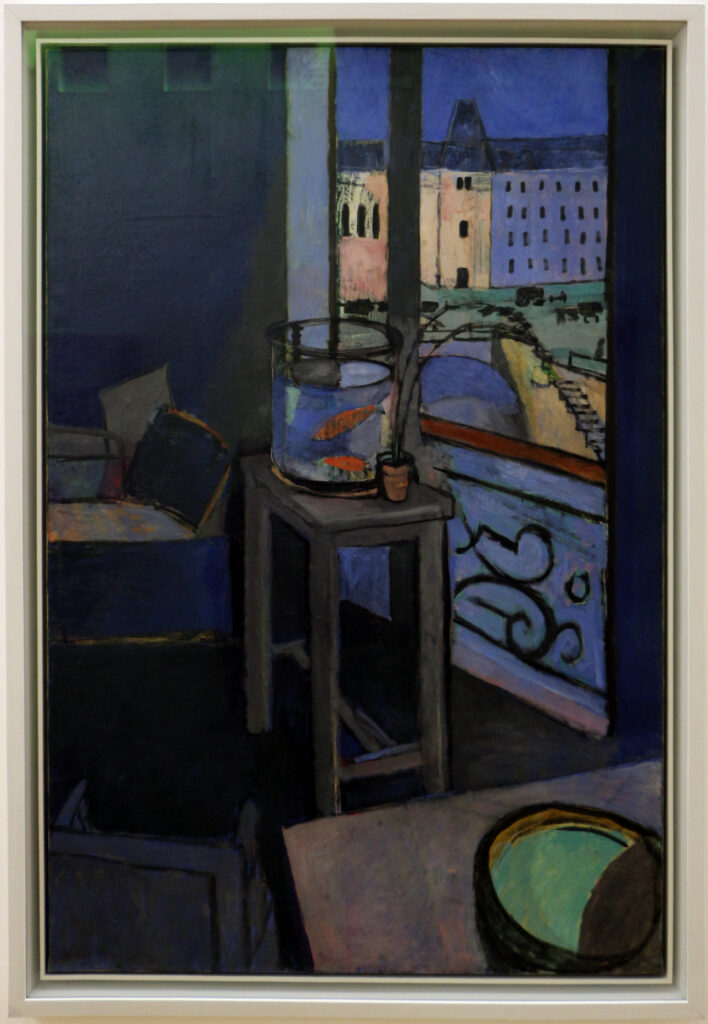

The same year as Matisse’s abstract Notre Dame painting, he did Interior with a Bowl of Goldfish, a composition that includes two of his signature motifs—a window view and a fishbowl. This window view is quite specific; nothing is abstract here, but everything is stylized with a color palette that includes Matisse’s favorite cobalt blues. He is borrowing from Cézanne (his artistic hero) a multiplicity of points of view—the window side table is viewed straight on, but the corner of the vanity with a green water bowl is seen from above, and the cityscape is shown from yet another point of view.

Matisse discovered goldfish bowls, used as a decoration or a meditative device, during his stay in Morocco, and on his return to France, he installed one for himself. Because the French word for goldfish is poisson rouge (“red fish”) and he was a redhead with a beard, the “rouge” fish became his signature in his paintings—a sign of his presence in the space he was painting.

Immediately after WWI, Matisse spent most of his time, especially in the winter months, renting rooms in Nice hotels. Moving on from both the austere palette of his wartime pictures and his forays into abstraction and Cubism, he returned with renewed energy to his own style of bright, masterfully combined colors and figurative representation. His Interior in Nice is a perfect example of the artist’s style in the 1920s and 1930s. The French window is wide open, admitting the light and views of the Promenade des Anglais (Nice’s main boulevard alongside the sea, where all the holiday restaurants and hotels are). The sea is calm, and sunlight is pouring in. The relaxed atmosphere of the Riviera town is personified by the languid pose of a woman sitting by the door. You can almost smell the sea air and lavender scent of a hot afternoon in Provence. In many paintings, both earlier and later, Matisse would flatten the images and use stronger colors, but in this and a few other pictures from this period, his colors are “Renoiresque” pinks and greens, and the interiors are quite naturalistic. This is also a picture that is easy to understand, with none of the complex symbolism and construction that imbued iconic Matisse pieces like 1911’s The Red Studio or his artistic manifesto in The Joy of Life.

Matisse’s windows are almost like notes in his private diary—pictures that reflect his travels and moods throughout his life.