Food for the Soul: Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

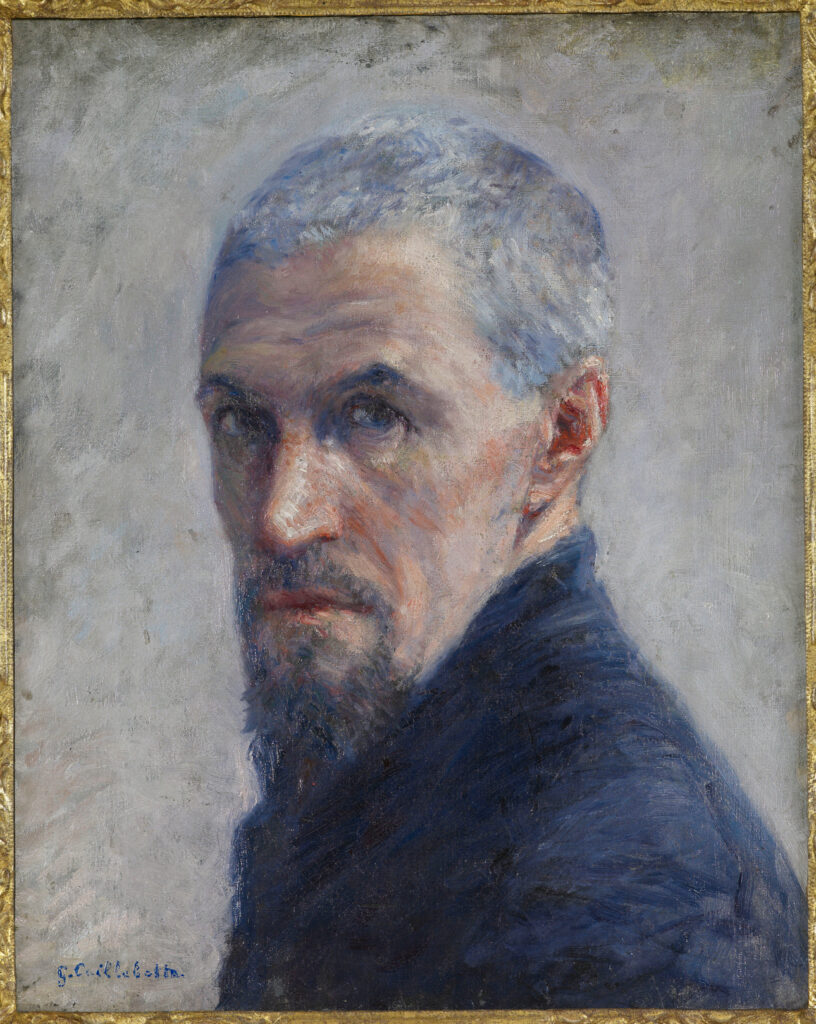

Personally, I love themed art exhibitions because I always learn from them. I learn about pictures that I have never before seen or sometimes gain an understanding of an artist’s evolution of style. Many painters have favorite motifs (Cezanne’s apples, van Gogh’s olive trees) or subjects (Renoir’s nudes, Ribera’s old men), and a themed exhibition can highlight such preferences. In the case of the French Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte (my favorite artist), this motif was the world of men.

The current exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, titled Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men, highlights this choice of painting mostly male models. In the context of his contemporaries—painters like Renoir, Degas, and Morisot—this focus was unique. In Caillebotte’s family, there were four boys (no daughters), and he completed education in a military academy, fought in a war, was a member of a sailing club, and trained as a lawyer and architect. He was, therefore, steeped in all-male environments and the high-achieving masculine activities typical for the upper-class lifestyles of his time. He did paint some landscapes and even flower compositions, but his forte was male portraits and scenes showing men in “action”—walking, kayaking, sailing, playing cards, and so on. This particular focus makes him stand out in the world of Impressionism that is otherwise populated by so many images of women—whether dancers, mothers, laundresses, nannies, or maids. In addition to his masculine thematic slant, his architectural approach to compositions makes his pictures truly outstanding.

Even though there is no proof that Caillebotte ever tried his hand at photography (a technology that had been available for a good 40 years by the time he created his first important picture, Floor Scrapers, in 1875), his paintings are often framed and composed like reportage snapshots. They feel modern to our contemporary eyes because we are accustomed to images of people caught in motion, with parts of their bodies cropped or out-of-focus faces. Floor Scrapers is a composition where the side walls are cropped, the point of view is high (as if it were a photo taken from above), and the room’s interior is fairly dark, lit only by a bluish reflection from the window. The “boxed-in” feel of this composition reinforces the message that this is a picture of the lowest class of workers using their brute strength for manual labor, like prisoners. These kinds of socially accusatory pictures were numerous in late-19th-century France in the iconography of Jean-François Millet, Gustave Courbet, and Edgar Degas. It is the composition however, that makes this painting so arresting and memorable. This debut painting was rejected by the Salon in 1875. The following year, Caillebotte threw his artistic lot in with the Impressionists, and he never again tried to join forces with the establishment art world, despite his elevated social position.

Caillebotte’s unique, “photographic” compositional style could not be more obvious than in his brilliant picture titled Bathers, one of the many paintings brought to the Getty exhibition from private collections. Here, the artist catches the swimmer the second before he plunges into a river. The image is also cropped on the edges so that both the images of a tree and a man climbing up are trimmed, increasing the sense of immediacy. It is as if we are casting a quick glance to catch a moment of activity at the riverbank.

Even when Caillebotte wanted to show a mundane activity, such as a walk on a newly constructed metal bridge, his style was profoundly his own and modern. On the Pont de L’Europe shows three men on the bridge who are all grouped on the left: one is standing, one is leaning on the rail, and one is just “leaving the frame” in long strides. If it were a photo, this would be a fast snapshot of people moving on a bridge. However, this is an oil painting that took time to create. The exhibition’s curators have gathered drawings and oil sketches that attest to the fact that nothing in this picture is accidental; Caillebotte planned the positions of all three models and made numerous studies for this painting and the similarly themed Pont de L’Europe (now at the Petit Palais in Geneva). The men in this picture are not the main theme—it is the advance of technology. The new steel bridge and the train below are the subject here.

Haussmann’s remodeling of Paris, which introduced high buildings with large, wraparound balconies, brought to that city an opportunity of new points of view, and Caillebotte took advantage. He obviously found very alluring the extreme shortening of perspective and the pattern of cobblestones that could be seen from above. For a painter of urban views, balconies have always been irresistible; Caillebotte painted numerous views from balconies, but this one (Boulevard Seen from Above) seems to be the most daring. Like in his river pictures, his image gains dynamism by showing a swirl of the stone circles, the twist of the branches around the tree and the slanted slashes of things seen from above: a bench and the shoulders of passers-by. Caillebotte was an artist before his time—imagine what he could do if he could draw views from an airplane or a high-speed train.

Caillebotte’s idiosyncratic style is not limited to his own compositions. His interpretation of motifs typical of his fellow artists’ work is also interesting. A picture of people playing cards has a long tradition in art, from Bruegel, Caravaggio, and Georges de la Tour all the way to Cézanne (whose famous card-player paintings came in just a few years after Caillebotte’s).

Caillebotte’s The Bezique Game is practically the only group portrait that he ever did, and it shows various close friends at a game that tout Paris was passionately playing at the time. Unlike other card-playing pictures, this one does not set the painter apart from his models (e.g. as when Cézanne was observing local peasants). Here, the participants are Caillebotte’s social equals, all of them affluent bachelors, playing in his comfortable Boulevard Haussmann apartment. This is a picture of male bonding (with a good dose of rivalry, given that the player on the left is about to break the bank) rather than a picture of strangers hired to pose. In a way, Caillebotte does what Morisot and Cassatt did with their pictures of mothers and children—he paints a world to which he alone has access, a world that is closed to external observers.

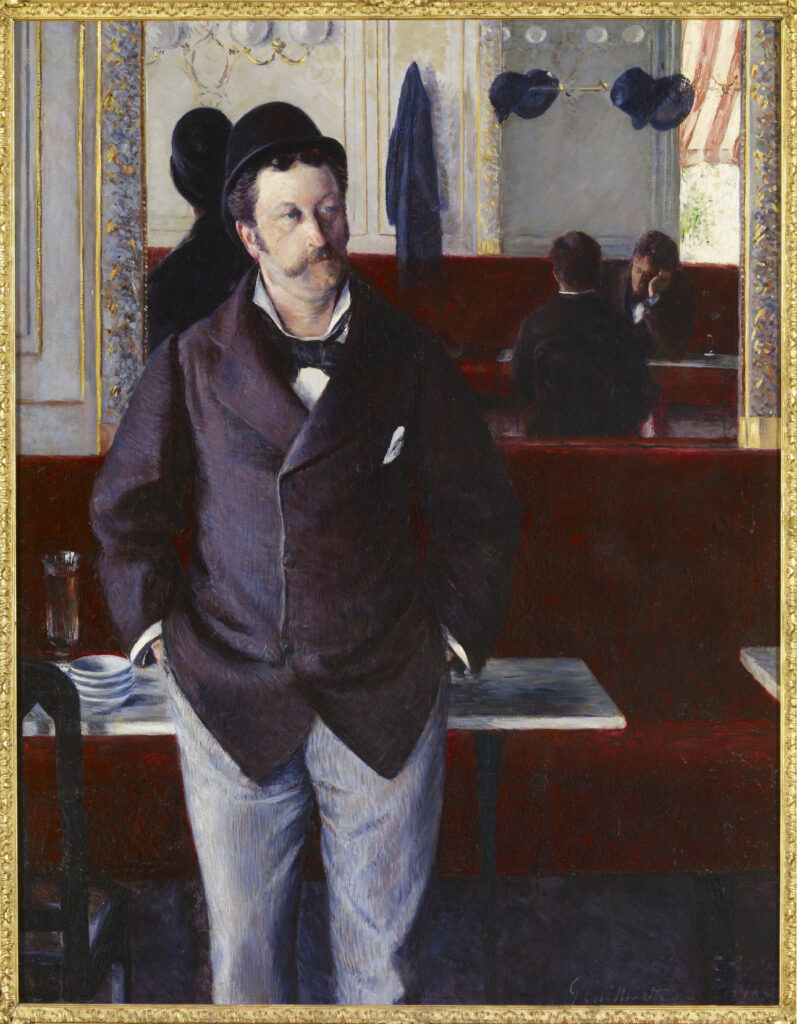

Caillebotte’s In a Café predates both Manet’s A Bar at Folie-Bergère and Degas’s Dans un Café—iconic images of people in a Parisian bar—and again his approach is somewhat different from the “anthropological” observations of other painters. Here, he paints a man dressed as a bar regular, a man who seems to be swaying from drinks already imbibed, leaning for support against a marble-top table with a mirror behind him. His shirt-collar is a bit disheveled, and he is standing in a casual pose. However, Caillebotte did not actually paint a casual drinker in a local bar—this is a portrait of Albert Courtier, a family friend and notary who is hardly a louche bar patron. It is a careful composition where the artist is using reflections in the mirror, as well as the sunlit window onto outside, in a manner that evokes the old masters: Dutch Baroque views of open widows and Velázquez reflections in a mirror. Nothing is ever really casual in Caillebotte’s paintings; his compositions are cerebral, full of erudite clues and drawn as carefully as the yachts that he designed.

One of the stars of the exhibition is a painting that is a proud acquisition of the Musée d’Orsay, and as such, sometimes hard to see in Paris because it makes so many tours of various French museums and goes out on loan to exhibitions. Boating Party was acquired by d’Orsay in 2022 thanks to the support of LVMH (those millions of Louis Vuitton bags finally served a grand purpose), and it is one of the best pictures among Caillebotte’s “specialty” of sailing and boating paintings. The artist designed yachts, was heavily involved with his sailing club, and spent a lot of time boating, especially after he moved to a country house on the river. His boating paintings always have an immediacy that is not found in Renoir’s or Sisley’s pictures of people on boats. Caillebotte’s paintings are often from the point of view of someone inside the boat—low angles and close to both the boater and the water. Boating Party is such a picture; we are in the boat together with the man pulling on oars. He is clearly neither a contestant in a race nor a boathouse worker. He is a city gent, complete with a top hat, who happens to have rented a boat for a bit of physical exertion, perhaps to clear his head since he seems to be preoccupied with something. You can construct a whole story around this “genre scene” while admiring Caillebotte’s skill in rendering water, as well his brilliant composition of crisscrossing stripes—the shirt patterns, the boat slats, the oars, and the position of hands and legs. Everything in this picture is slanting and crisscrossing, adding dynamics to this brilliant portrait of movement on water.

Gustave Caillebotte died young after barely 20 years of creating paintings that were much less appreciated by his contemporary art critics than they are now, 131 years after his passing. His bold compositions were too dramatic for academicians, and his painting style was perhaps too academic in comparison with Seurat’s Pointillism or Monet’s Impressionism. Dying in his mid-40s, Caillebotte did not have the time to acquire the artistic patina of respectability that fellow artists like Renoir acquired with the passing decades. Only now, in a different century, can Caillebotte’s unique artistic eye be admired in equal measure to those other artists that he championed and supported.

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men, an exhibition featuring about 100 paintings and drawings, is on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum from February 25 to May 25, 2025, to be followed by a showing at the Art Institute of Chicago from June 29 to October 5, 2025.