Food for the Soul: A Man Who Never Stops Looking – David Hockney Show in Paris

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Sometimes, with artists who died young, we can only wonder what greatness they would have achieved had they lived long enough. Such a list could include Raphael—the wunderkind of the mid-Renaissance—the talented Impressionists Frédéric Bazille and Gustave Caillebotte, who could have created masterpieces had they lived as long as Monet, and Egon Schiele and August Macke, geniuses of Vienna’s early 1900s art who both died in their 20s. Then, there are other artists whose late output did not match their early genius. Botticelli’s late art is less luminous and interesting than his early paintings, and Giorgio de Chirico will always be admired most for his early Surrealist art.

David Hockney is in neither category. He has had time to create, evolve, and grow, and he has only become better with age. He is now 88 years old, and he announced that the David Hockney 25 exhibition that recently opened at Fondation Louis Vuitton is to be his last show. Hopefully not, but let’s take a look at this show, which is certainly the most important art event of the year.

It starts with Hockney’s beginnings when he studied at the Royal Academy in London, already precociously talented and at the time working in the styles of conceptualism or Art Brut that dominated the 1950s and 1960s scene in the UK. If he had remained at that stage, his paintings might end resembling so many pictures in the style of Jean Dubuffet or conceptualism that clog museums today, often with no emotions to evoke. Luckily, the 27-year-old Hockney, a swanky Brit gay artist in search of both brighter light and a better social scene, moved to Los Angeles.

Drenched in Sunshine

The blinding light of Southern California had the same effect on his paintings as the sun of Arles had on van Goghs’s canvases, which got saturated in yellows and vivid greens.

I love Hockney because he so often is playing with ideas. A Bigger Splash is a painting that does that by answering a question—the question of how to show something that isn’t there or something that cannot be painted. This picture does both things. It shows you the diver who has just plunged into the pool; the splash is there, but you cannot see the person. It also shows you something that the visual arts are inherently unable to render—a sound. We look at the image of a pool with water erupting, we know about the “splash” from the caption, and our mind immediately adds what is missing and obviously connected—the sound of a gigantic splash that a diver makes jumping into a pool on a summer day. We do not need to see an actual diver to experience this scene. This is where the genius of Hockney lies; he painted the impossible in a brilliant and bold composition.

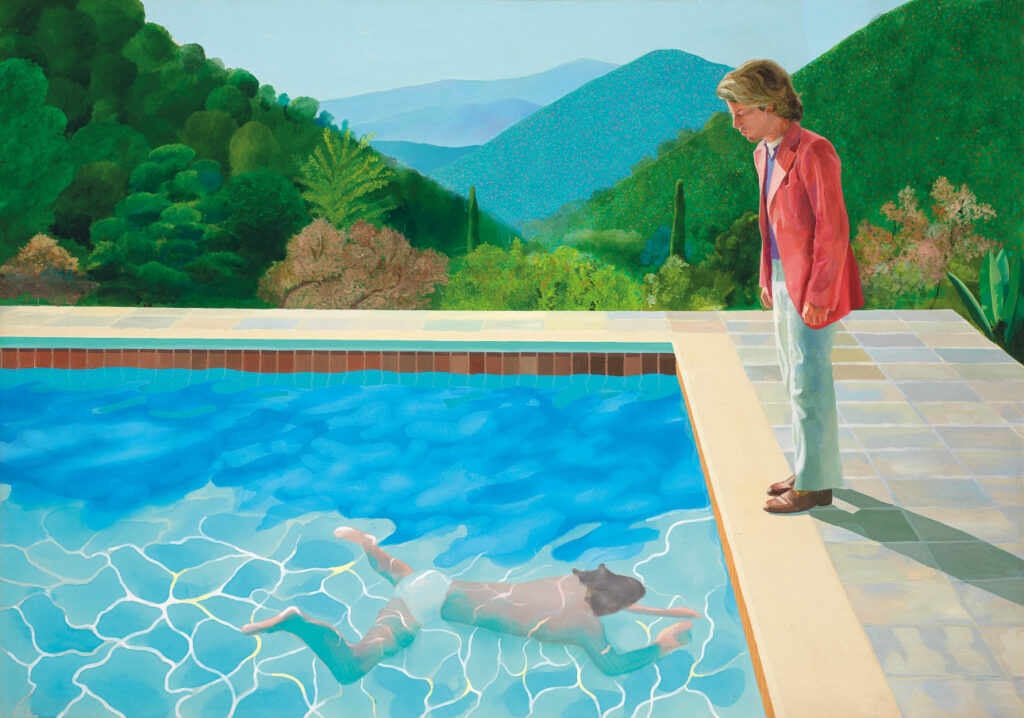

If A Bigger Splash and Pool with Two figures (both showcased at the exhibition) are canvases that represent Hockney’s “Los Angeles period” and his love of the brilliant light of the south, there is another important picture from that period that speaks to Hockney’s lifelong devotion to portraiture, including his leitmotif of double portraits.

In Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, he plays with another visual convention. Painted in 1968, it shows contemporary people in a modern room, but the structure of this picture is positively medieval. A lot of religious pictures—altars with Madonna enthroned or pictures of saints—would be composed in this type of stiff, symmetrical design. This painting is deliberately symmetrical; not only the furniture and the two Hockney friends but even the books on the coffee table are symmetrical—four tomes on each side. The window behind completes the feeling of an altar painting, where often a window or columns would provide a background. Yet into this formal structure Hockney inserts a modern interior design, two thoroughly contemporary people, and a rebel theme of a gay relationship (in England, the criminalization of homosexuality had been abolished barely a year before this was painted).

Hockney’s People

Today, the Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy portrait is a classic of 20th-century art, but at the time, Hockney’s artistic path went against the grain of what was fashionable and prized in fine art. Conceptualism, Abstractionism, performance art, etc. were then en vogue. Paintings of people were not considered avant garde.

A room devoted to portraits documents Hockney’s lifelong devotion to figurative art. He has mostly painted his friends, family, and co-workers. Apparently, he refused to paint an official portrait of King Charles III, saying that he does not know him well enough to paint him. For his decades of portraiture, he has used many techniques: traditional oil, acrylic, charcoal, and watercolor, but also digital images done on an iPhone and iPad, and, most fascinatingly, huge digital scans that form tableaux with the compositional complexity of Renaissance battle scenes. These are portraits of people first photographed on all sides for 3D images and then designed into a space created by the artist, thus becoming a 2D composite image that is dubbed “photographic drawing.”

Like Rembrandt, Hockney has painted himself throughout his life, and like his predecessor, he has sketched himself with different facial expressions. There is a series of whimsical iPad self-portraits showing him with expressions ranging from silly to somber to mysterious.

Yorkshire and Normandy

With his 1960s works like A Bigger Splash, as well his portraits and landscapes of Arizona and California, Hockney had already earned his leading place in the history of modern art, but he was not done stretching the possibilities of visual artistry.

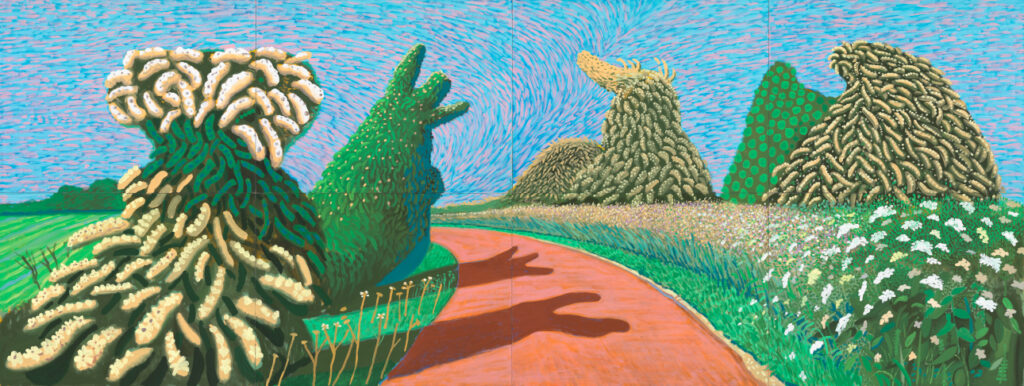

In the “wow” section of the exhibition are rooms where paint and iPad images (either framed and sized like classic paintings or shown on multiple screens joined together to the size of giant airport ads) place Hockney as a direct artistic descendant of van Gogh and Matisse, those pioneers of wild color and unrestrained lines in modern paintings. All this thematic brilliance would be enough for us to like his art, but the fact that he interprets it with fauvist neon colors and the mediums of oil, acrylic, iPad, and digital design raises his artworks to the level of an exceptional visual experience.

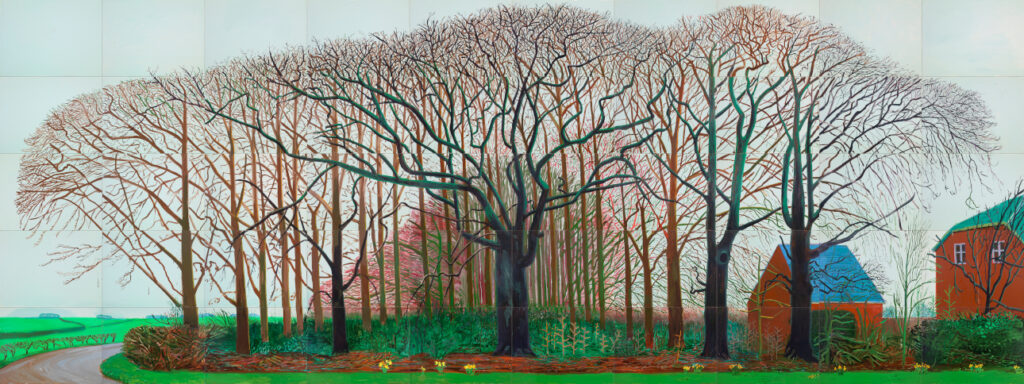

Hockney’s “Yorkshire period” yielded traditional watercolors and traditionally sized oils, but the most entrancing works are giant, multi-canvas pictures that consist of anything from 8 to 50 canvases. Many painters, with time, seek grander and grander formats for their work, but Hockney dwarfs them all with his landscapes that approach the actual 1:1 ratio of trees and roads.

182.88 x 487.7 x 0 cm (72 x 192 x 0 Inches) © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

Living in Los Angeles, you eventually realize that there are hardly any seasons. The same sunshine is glaring in November as in May—only the temperature is different. When Hockney moved from California back to England in 1998, he got back the seasons. He could observe weather that can sometimes change a few times a day, and he could look at the same landscape that would utterly metamorphose with the change of season. Settling in Yorkshire between 2004 and 2013, he would paint trees which, upon losing their leaves, would change an entire road or field by revealing the land behind them. Hockney revels in views of a forest road with freshly cut timber logs and clumps of impossibly vibrant greenery by the roadside. The saturated, multi-shade green of the Yorkshire countryside must indeed have felt like a breath of fresh air when compared to the dusty, reddish-brown chaparral landscapes of the Santa Monica Mountains. In views of Nichols Canyon or Arizona’s Grand Canyon that Hockney painted in the 1980s, he would simply paint them brick-red or even purple, whereas in views of Normandy, he did not need to change the color of the grass and leaves—he mostly kept them green, yellow, or rust, depending on the season. Nature had already provided a varied palette. He wouldn’t be a color master, though, if he had not included purple tree trunks, pink road asphalt, or the orange fields that dot his paintings here and there, reminding everybody that these were painted in the 21st century, and “this isn’t naturalism anymore, Dorothy.”

Hockney has always been fascinated with the technology of image creation and perception. He famously investigated several hundred years of European paintings to posit that many paintings after 1430 may have been created with the aid of optical devices to enhance verisimilitude. The artist himself has embraced all new technologies as they have appeared: the Polaroids and faxes of the end of the 20th century, and then the iPhone, iPad, and digital imaging of the 21st century.

During Covid, Hockney was living in a farmhouse in Normandy. Armed with an iPad, he would create iPad pictures of land around his prperty, pictures of single trees, and garden views by moonlight. In those pictures, deceptively simplistic, Hockney sees it all: a detail of a pond with marsh marigolds, a shadow falling down from a small window in a barn, a spray of sunset light seen through a small bush. Since these are iPad screen images, they can be lit from inside, they can be blown up to a huge size, or they can be shown as a process (the Procreate graphic software on the iPad allows one to show the progression of a drawing).

If there can be a unifying idea behind Hockney’s artistic output over the decades, and across all the mediums that he has used in artworks related to dozens of locations across the globe, then perhaps it is this: the artist is always looking, and he is looking closer than anyone else does. He is looking at the world around him from small roadside weeds to enormous canyons, he is looking at museum masterpieces and Polaroid snapshots, and he is looking at ways that the medium of digital photography or drawing changes the perception of people or landscapes. This is what this retrospective show captures so well—the enormous breadth of Hockney’s visual prowess and the joy that his visual explorations can bring to people confronted with his monumental Bigger Trees Near Warter or Bigger Grand Canyon.

The David Hockney 25 exhibition is open at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris between April 9 – August 31, 2025.