Destinations – Tuscany

By Nina Heyn

A “must-see” list for Florence usually includes checking out Renaissance art at the Uffizi Gallery, having a quick look at Michelangelo’s David, and taking a walk to admire the incredible feat of architecture of the Florentine Duomo. However, there are many other less obvious art history treats in Florence. One of them, in place since the mid-17th century but closed for renovations for the last eight years, is the celebrated Vasari Corridor—the secret Medici passage high above the city streets. The corridor reopened to the public a few months ago, and I was happy to check it out.

The Vasari Corridor

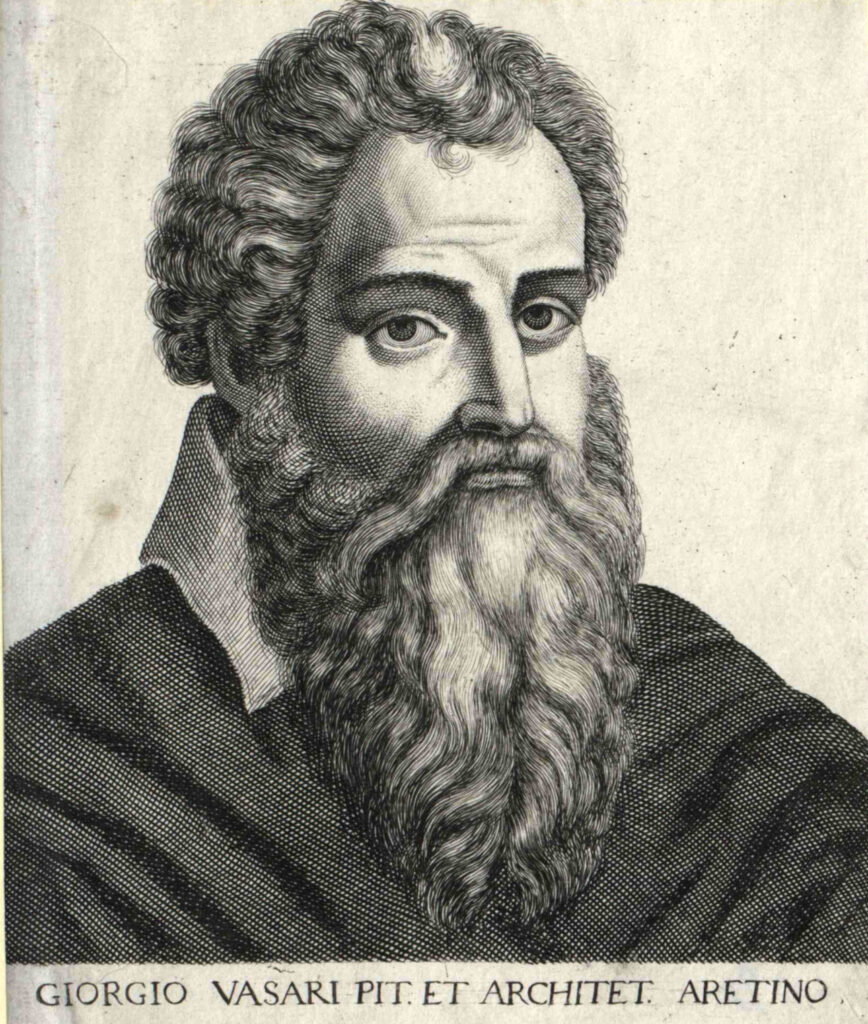

Any CEO presented with a chance to shorten his commute to the office would jump at the opportunity, and it was no different several hundred years ago. Grand Duke Cosimo I de Medici (1537-1569) had a similar need in 1565, but his idea of easing the passage between home and office was more extreme. As a ruler of Florence with many dissatisfied citizens, Cosimo wanted to avoid mixing with the populace in his daily sorties from the family palace across the river to his office (Uffizi) as well as the Palazzo Vecchio, the Florentine city hall. (The Palazzo Vecchio is still in operation—people get married there.) He commissioned his court painter and architect Giorgio Vasari to design an elevated passageway that would connect all three locations high above the city streets.

Vasari, a good architect and a gifted painter who decorated many rooms of the Medici buildings, is mostly well-known as the author of the first art history book, The Lives of Artists, which to this day serves as a valuable biographical source on 16th-century painters and architects. The task set to him by his employer was to design an enclosed corridor permitting discreet crossings between the three buildings while avoiding the crowds (as well as potential protesters or even assassins) that might be encountered in the streets.

The passage is about a kilometer long, and it is a feat of 16th-century architecture, running well above the streets, bypassing a house whose owners refused Medici’s demolition request, and running over the famous bridge called Ponte Vecchio. Before the building of the Vasari Corridor, the bridge was the site of a food market, but Cosimo was not happy about the fish smells (who would be?), so he had the fishmongers replaced with goldsmiths, whose tantalizing stores are still in this location today.

Until the recent renovations, the corridor was decorated with statues and portraits, but since the December 2024 reopening, the passage only allows a limited number of visitors (you have to reserve a guided tour), and all paintings and decorations have been removed to the climate-controlled Uffizi display rooms. The famous collection of self-portraits is now housed in a wing of the gallery.

The remodeled corridor looks very bare and is accessible only in the part between the Uffizi gallery, which is where the tour starts and the Boboli Gardens. It snakes all the way along the Arno river and at some point overlooks the nave of the church of Santa Felicità. There is a balcony (now barred from tourist access) that overlooks the church, which enabled the Medici family to participate in Mass without mingling with the churchgoers below. For the rich, privacy has always been at a premium, except that nowadays, privileges like a private chapel access have been replaced with modern conveniences such as VIP rooms and private planes.

The corridor eventually leads to an exit into the charming Boboli Gardens—a vast park, designed by Cosimo’s architects at the direction of his glamorous Spanish wife, Eleonor of Toledo.

The views from the Boboli Gardens terraces, and further down from the connecting Bardini Gardens, are the best ones in Florence, giving an eagle’s view onto the panorama of the city. Both locals and tourists like to escape the summer heat of the day among the shaded alleys of the park.

The Medici Villas

The Medicis’ architectural influence on Tuscany went far beyond Florence’s walls. The countryside as far as Pisa and all around Florence is dotted with beautiful historical estates of the Medici family. Their country villas served as farms, providing palatial kitchens with olives, wine, and agricultural products, but also as summer homes away from the city heat and often as informational outposts to provide advance warnings of any impending invasion. A succession of Medici rulers built the estates throughout the countryside, marking their ownership of the territory and contributing to the family wealth.

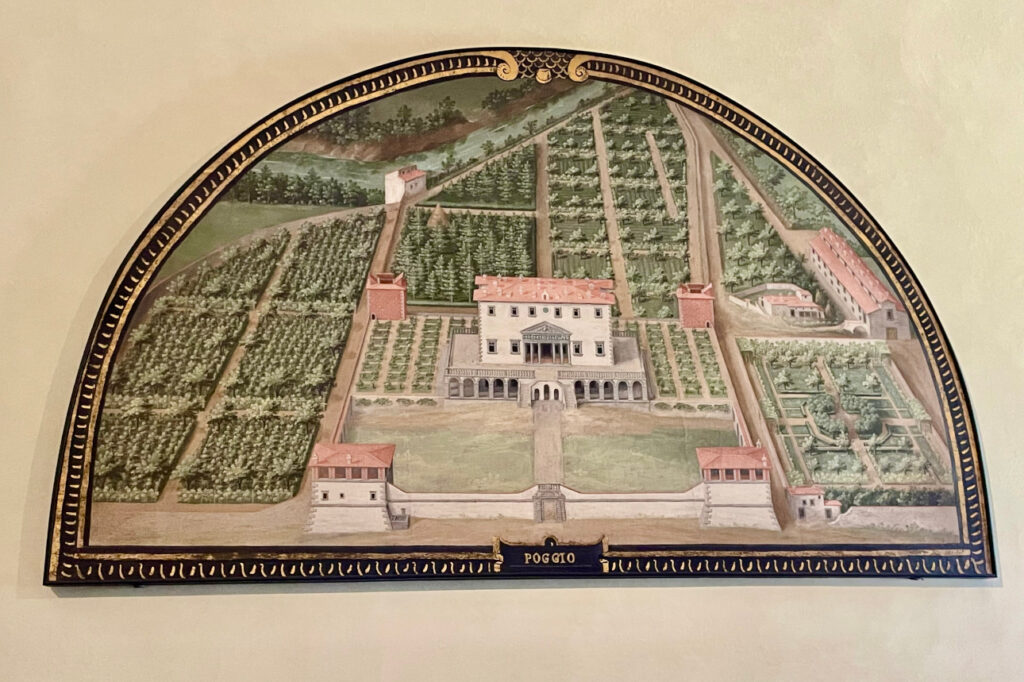

Villa La Petraia houses a collection of half-moon-shaped paintings called lunettes that Ferdinando I de Medici commissioned in 1599 from Dutch artist Justus Utens. The 14 paintings depict the estates owned by the Medici family at the turn of the 17th century. Utens painted the palaces (though they are called “villas,” their size and grandeur have little to do with the contemporary notion of a nice house) and their surrounding lands—olive groves, wineries, and formal gardens—with great accuracy and the astounding precision of a bird’s-eye view. The design of these pictorial records was a collaboration between an architect, who kept the proportions of the design to scale, and Utens, who rendered the images of each garden and grove down to the smallest tree.

One of the most beautiful Medici residences is Villa Poggio a Caiano near Prato, built by Giuliano da Sangallo for Lorenzo the Magnificent, with frescoes by Pontormo, Alessandro Allori, Andrea del Sarto, and Franciabigio. This villa served as a pre-wedding retreat for Eleanor of Toledo and her future husband Cosimo I when she arrived from Spain. The betrothed couple stayed at this villa when they traveled through Medici lands to be wed with great pomp in Florence.

The centerpiece of this residence is the great hall, which was conceived as a display of the magnificence of the family. In the frescoes by Allori, Franciabigio, and del Sarto, every wall is covered with exotic scenes of grand receptions amid wild animals as pets, servants carrying dishes, and warriors and rulers all clad in extravagant garb. This room alone is worth a sightseeing stop when traveling through Tuscany.

When I visited, as an additional treat, there was a temporary display of Pontormo’s Visitation—one of the most beautiful Renaissance artworks ever. Just take a look at the bold composition and incredible colors of this strikingly modern composition of four figures, which have almost sculptural depth and clarity of lines. Usually, this large panel is located in a church building in the nearby community of Carmignano, but it was moved during the church restoration.