Food for the Soul: Michelangelo – Mind of the Master

Sweat and toil of the master who never wanted you to see it

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Michelangelo Buonarotti. Head of a Child with a Cloak around the Head. Mid-1520’s. Collection and photo credit: Teylers Museum, Haarlem.The Netherlands. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

Most of the time, on order to experience Michelangelo’s art first hand, you have to be in Florence or Rome. His frescoes and sculptures do not travel. It is a rare treat therefore to see something by his hand that is outside Italy. Three museums – Teylers Museum in the Netherlands, Cleveland Museum of Art and the Getty Museum in L.A. have jointly mounted an exhibition of the artist’s drawings, some of which have not been shown outside Europe before. The drawings are selected to show both his artistic development and the genesis of some of his most iconic works.

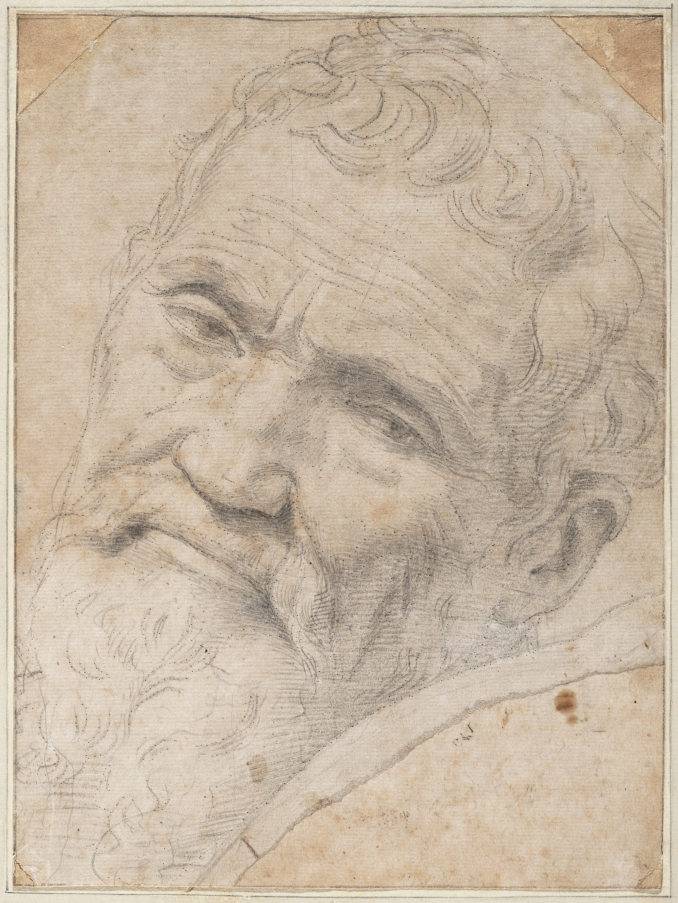

Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli). Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarotti. c. 1550. Collection and photo credit: Teylers Museum, Haarlem.The Netherlands. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

Michelangelo sculpted his marble statue of David when he was 26 years old and the Bruges Madonna a couple years later. He was in his thirties when he started painting the incredibly inventive and complex ceiling frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Almost from the beginning he lived in the aura of an artistic genius, which he of course was, but he wanted more. Like many artists, he preferred his admiring public to believe that his was a God-given gift that would allow him to come up with works of art spontaneously. “I saw an angel in the marble and carved until I set him free” is one of his famous quotes.

The reality of creating his art was different – the amount of sweat and toil that Michelangelo has put into preparing his frescoes and sculptures is enormous- but he was very good at hiding the fact. His contemporaries reported that the master was constantly drawing, sketching, and working out various designs. It is estimated that Michelangelo, during his long life (he died at 89) must have created about 28,000 drawings but only about 600 have survived to our times. Apart from some work sketches and artwork he offered to his friends, Michelangelo has been systematically destroying his paperwork. Surviving drawings are dispersed in various museums and libraries, and it is rare to be able to see a group of them together.

Michelangelo Buonarotti. Study of a Mourning Woman. c. 1500-1505. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

The Getty is a proud owner of a very recently discovered and an exquisite drawing of a mourning figure of a woman. It could be the Virgin Mary at the Cross, except that traditionally such a figure would be on the right of the cross (“stage left” in theater lingo). This figure is positioned on the other side and therefore a bit mysterious – there are no surviving artist’s works that would utilize this design. The drawing itself was discovered in 1995 in an appraisal at Castle Howard in England, giving us a renewed hope that there are still world’s nooks and crannies housing some undiscovered art treasures.

The core of the current exhibition comes from a collection of Teylers Museum in Haarlem, one of the oldest, formal art and science institutions in Europe. It was established in 1784 as a bequest of a wealthy investment banker Pieter Teyler whose patronage came at the time when Dutch Enlightenment produced some of the greatest scientists of the era but when universities did not conduct scientific research. Teyler closed this gap by creating in his will a “musaeum” – a center of scientific study. With time, the collection of minerals and scientific instruments (still on display at the same place) was expanded by adding a collection of art. Here we have to backtrack over a century to one of the most amazing royals of Europe – the Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), whose passion for Italian culture has led her to extreme actions. She became queen at the age of six when her famous father and a leader of the Protestant cause, King Gustavus Adolphus, has died in a battlefield during the Thirty Year’s War. She was crowned at eighteen but she soon started chafing at her royal duties in her straight-laced Protestant Sweden. What she wanted was Italian art, music and culture. This is the time when she has purchased an album of Michelangelo’s drawings from a Dutch merchant and these drawings ended up at Teylers about 150 years later. Christina was as brave and uncompromising as they come. After reigning for ten years she abdicated the throne, converted to the “enemy” religion of Catholicism, and moved to Rome, taking her art collection with her. She established her life there as a patroness of theater and music, a sponsor intellectual salon debates, and a prominent art collector.

So, in part thanks to the Queen’s passion for Italian art, we can now admire an assembly of precious sketches and drawings from an artist who would systematically destroy his preparatory drawings and sketches throughout his life. He would spend a lot of time working out the composition and positioning of bodies in his frescoes or sculptures, but once he worked out his design problem, he did not want to retain any “artistic notes.” His reluctance to preserve any drawings was well known. There are records of his ordering an assistant to burn stacks of drawings, a letter to his father asking him not to touch any of his papers, and some correspondence from Duke Cosimo di Medici where he laments that the artist did not spare any of his drawings from fire. With so little evidence of the creative process left behind, it is even more fascinating to examine what has survived.

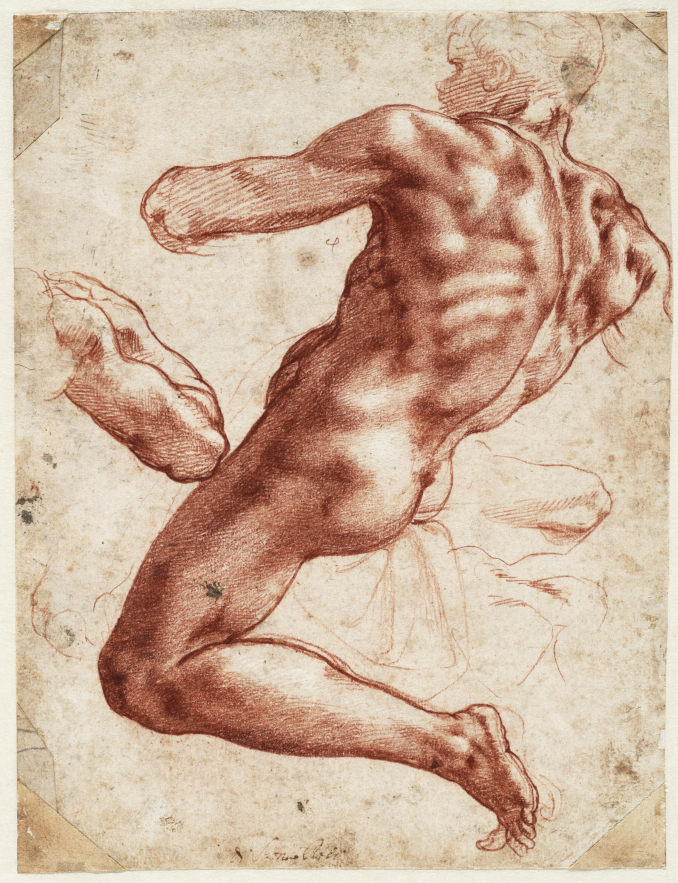

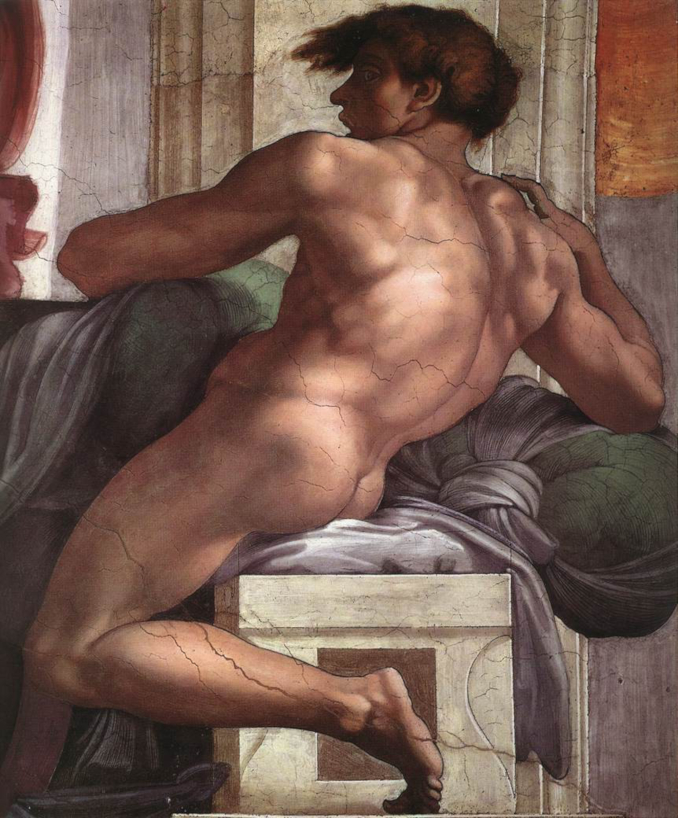

Michelangelo Buonarotti. Seated Male Nude. 1511. Collection and photo credit: Teylers Museum, Haarlem. The Netherlands. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

One of the most complete drawings is Seated Male Nude, drawn in red chalk and heightened in white, where the whole weight of the body is precariously poised on a big toe and every muscle is worked out with surgeon’s precision. Like Da Vinci, Michelangelo was an anatomist who studied human body at dissections, and he was a master of understanding bodies in motion. This beautiful drawing, a work of art in itself, is actually the preparatory study for one of the male nude figures in the Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarotti. Ignudo, detail from the Sistine Chapel ceiling. 1508-12. Vatican Palaces, Vatican City State. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain

In 1503 the city of Florence commissioned from da Vinci a large fresco depicting The Battle of Anghiari that we know from a famous copy by Rubens. Leonardo was famous for being slow in executing his commissions (it took him three years to paint The Last Supper) and, perhaps to spur da Vinci in his endeavor, they hired his avowed rival Michelangelo to paint a second battle on the opposite wall. Michelangelo produced a preparatory full-scale cartoon of The Battle of Cascina but the fresco never got painted. Neither did the da Vinci one.

Bastiano da Sangallo. A copy of Michelangelo’s The Battle of Cascina cartoon. 1542. Earl of Leicester and the Holkham Hall collection. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons: Public domain

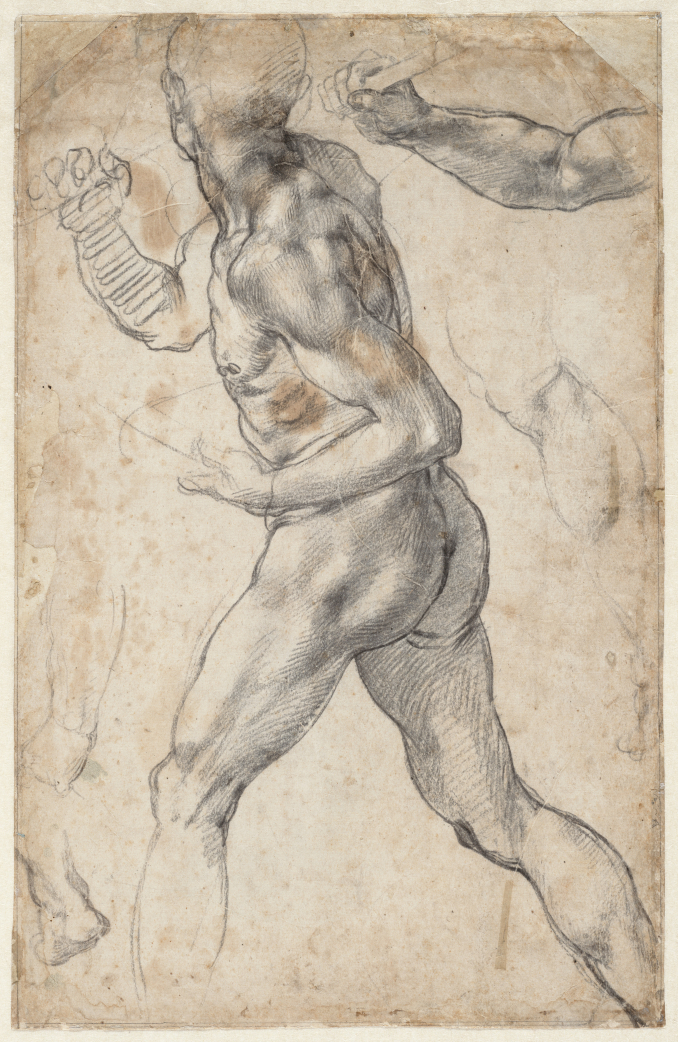

The Battle of Cascina preparatory cartoon was loved to death by artists who made copies of this composition. Only some scraps of the original survived, and various copies allow us to understand the artist’s intention. It depicts not the battle itself but a group of bathing soldiers surprised just prior to the battle. A Study of the Striding Male is a preparatory drawing for one of the characters, delineating even the smallest muscles in the twisting torso, and the plan of how the figure would fit amongst other intertwined bodies.

Michelangelo Buonarotti. A Study of the Striding Male.1525-30. Collection and photo credit: Teylers Museum, Haarlem. The Netherlands. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

The exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles is open between February 25- June 7, 2020. There are numerous accompanying events during the exhibition, such as sketching sessions, public discussions led by curators, even an evening devoted to Tuscan wine tasting.