Food for the Soul – New York Big Five – MoMA

Marc Chagall. I and the Village (1911). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the world’s largest contemporary and modern art assemblage, has been in the avant-garde of modern art collecting for almost a century. Founded in 1929 by three enterprising society women who were art collectors and patrons, it has a dual mission of recognizing the best contemporary artists and being a repository of the best examples of modern art. The first goal is currently served by the “Cézanne Drawings” exhibition (ongoing through September 2021) and the upcoming “Reuse, Renew, Recycle: Recent Architecture from China” (September 2021–January 2022). As for the second MoMA goal, it is amply satisfied by the museum’s always growing collection of about 200,000 artworks (including paintings, architectural drawings, photographs, sculptures, ceramics, textiles, and documents), of which 90,000 can be viewed online. Only a small fraction, however, are able to be on display at any given time at MoMA’s recently renovated building in midtown Manhattan.

René Magritte. The Menaced Assassin (1927). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Visiting MoMA at any time is like discovering old friends, but with its recent reopening, MoMA has brought back not just perennial favorites but less well-known treasures from the vault. The museum’s fifth floor houses art from the 1880s to the 1940s—representing the explosion of styles, inventions, artistic pursuits, and stylistic discoveries that together constitute the notion of “modern art.” Some artworks are grouped there by movement or period. For example, in the “surrealist room,” the current display includes Magritte’s theatrical murder scene in The Menaced Assassin, Dali’s melting watches in The Persistence of Memory, and the haunting painting by Remedios Varo titled The Juggler. This last one is a recent acquisition; the 1956 painting by a Spanish artist (active in Mexico) is a great surrealist theatrical portrait of a medieval trickster who is performing for an androgynous crowd of people.

Henri Matisse. Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s “La Desserte” (1915). Gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx, 1964. Photo: Wikiart Public Domain

There is also a roomful of Matisses, including his Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s “La Desserte” and The Piano Lesson—pictures that are in every album of post-Impressionism. To quote an elegant phrase of MoMA’s curators: “Matisse remains one of the great joy-givers of the twentieth century.” His radiant Still Life, a dialogue with a Dutch baroque painting, has a complex artistic history. Jan Davidsz. de Heem was a very established painter of flowers and still lifes arranged in overflowing, eye-pleasing cascades of fruit, seafood, or luxury items. Moving between Catholic Antwerp and Protestant Utrecht, he lived at the crossroads of two religions and two approaches to material goods and Christian devotion. In his A Table of Desserts, painted in 1640, he married Catholic abundance with the austerity of the Dutch Republic in the complex structure and symbolism of the painting. Young Matisse copied this very famous arrangement when he was studying art, and many years later, coming upon his youthful art exercise, was inspired to tackle a complex composition in his fully developed, modernist style.

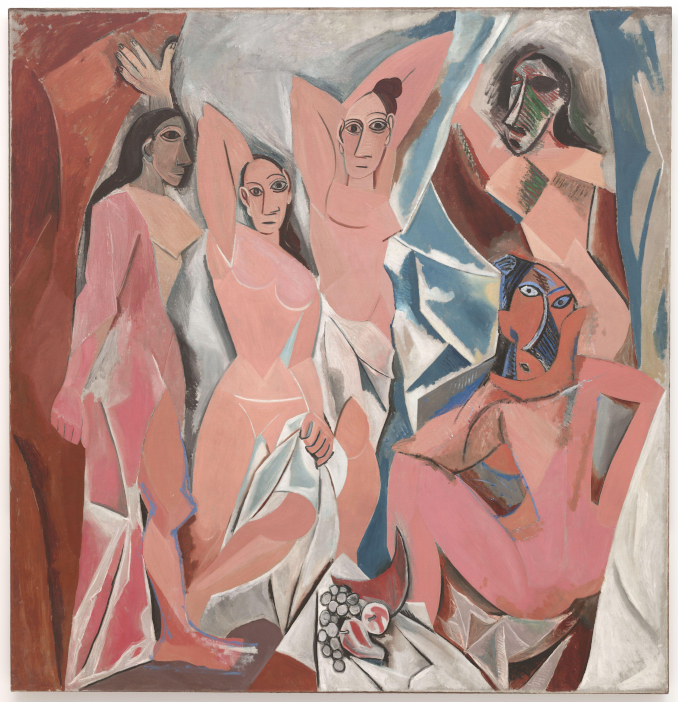

Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1906-1907). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Picasso room at MoMA is dominated by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. After having already experimented with many styles, Picasso painted it at age 25 as his manifesto of Cubism and reaching of maturity as an artist. Entire books have been written about this unchallenged milestone of art history, but it still never ceases to amaze. Picasso spent almost two years working on this painting that was to be his answer to Matisse’s fauvist art and his own transition into a new Cubist style. The canvas is a supersized 96 x 92 inches (244 x 234 cm)—the size of a 19th-century academic history painting—and features five prostitutes whose faces range from human to dehumanized. With this scandalizing painting, Picasso asserted his dominance in the art scene and, at the same time, pushed modernism in a new direction. MoMA managed to acquire it in 1939 (having to sell a Degas painting to raise funds), and it has been a perennial fifth-floor draw ever since.

Henri Rousseau. The Dream (1910). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Another painting that surprises with its size—which never comes through when seen in art books or on websites—is Henri Rousseau’s The Dream. The canvas is a large 10 x 7 feet, beautifully composed and planned (note the elephant peaking from behind foliage and the snake whose pink underbelly is easy to notice but not his true, dark, and full bulk), and painted with a sure hand. The woman (who Rousseau called Yadvigha—a Polish name, perhaps of a model he used) assumes the same pose on a couch as her artistic predecessors, such as Monet’s Olympia or even Titian’s Venus d’Urbino. Though Rousseau was unschooled in the sense of never having attended a formal art school, it is hard to fathom how someone so talented and sensitive to color, style, and art references could be scorned by contemporary critics as “primitive.”

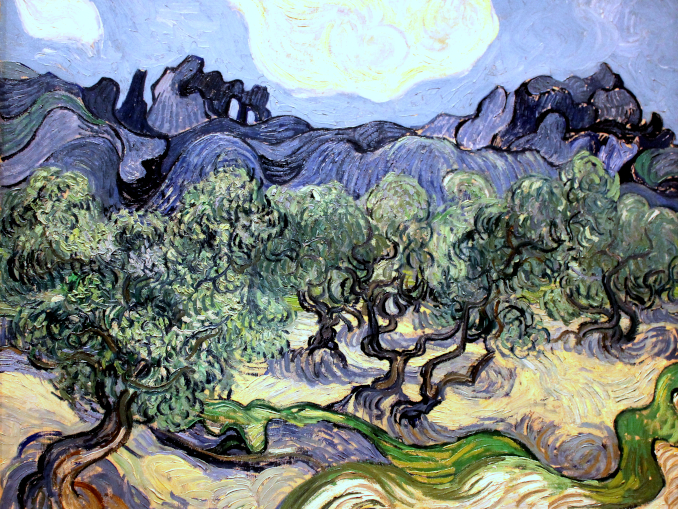

Vincent van Gogh Olive Trees in a Mountainous Landscape (1899). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

MoMA has devoted an entire area to so-called “Masters of Popular Painting.” This area features colorful and charming artworks by Morris Hirshfield (an artist born in Poland who emigrated to America), André Bauchant (French), and Bertha Trabich (American)—all painters who did not go through the traditional art school route but found their artistic voice nonetheless. Their paintings, which used to be called “naïve art,” were disdained by art critics and the museum-going public alike. When MoMA’s first director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., gave Hirshfield a one-man show in 1943, the exhibition was universally panned and contributed to Barr’s demotion. These days, Hirshfield’s delightful Angora Cat and Tiger are proudly displayed in this gallery.

Paul Cézanne. Château Noir (1903-1904). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

MoMA’s fifth floor is like a roomful of toys (or the proverbial candy store)—so many great things in one place. You can examine the best paintings by Cézanne (the father of a modern take on landscapes), enjoy Marc Chagall’s bulls and peasants in I and the Village, see Klimt’s Hope II, check out van Gogh’s The Starry Night and Olive Trees in a Mountainous Landscape (painted in 1899 as companion pieces when van Gogh was in the Saint-Rémy asylum), or you can enjoy one of the best Edward Hopper paintings: The Gas.

Gustav Klimt. Hope II (1907-1908). MoMA. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If you are seeking art as therapy for all the ills of contemporary life, MoMA is the place that will serve this function in spades. Wherever you turn, and on the fifth floor in particular, you will find an outburst of creativity, color, and shape that will inspire or soothe the soul.