Food for the Soul: Global Trade in Art, Part 4: The Americas

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

“The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind.” ~ Adam Smith in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

It is unlikely that the landing of Christopher Columbus in the New World looked as relaxed as illustrated by the 19th-century German landscape artist Albert Bierstadt. It is nonetheless an evocative rendition of a historic moment in global trade—the beginning of European access to the untapped natural resources of the Americas—including minerals and metals, plants and animals, human labor, and arable land. Everything that was becoming scarce in overpopulated Europe, or inaccessible due to wars with the Ottoman empire and Asian tribes, was suddenly able to be sourced in abundance in a different part of the world. However, for people who already occupied those lands, so serenely (and inaccurately) portrayed in Bierstadt’s painting, this was the beginning of a genocide. Entire nations and tribes would soon start disappearing—annihilated by occupation and enslavement but also by viral and bacterial onslaught brought through sudden biological contact.

Diego Rivera portrayed the trauma of this contact between civilizations with passion in a mural that decorates the national palace in Mexico. Diego Rivera was not only a leading 20th-century Mexican artist but also a highly committed political activist whose leftist ideology famously clashed with American capitalism, resulting in Nelson Rockefeller’s destruction of a mural Rivera painted for the Rockefeller Center in 1933. In a different mural, entitled The Spanish Conquest of Mexico (referring to the land that would actually have been the Aztec empire at the time—but everybody gets the idea), Rivera leaves no doubt as to how much he condemned the Spanish conquest of his ancestral land.

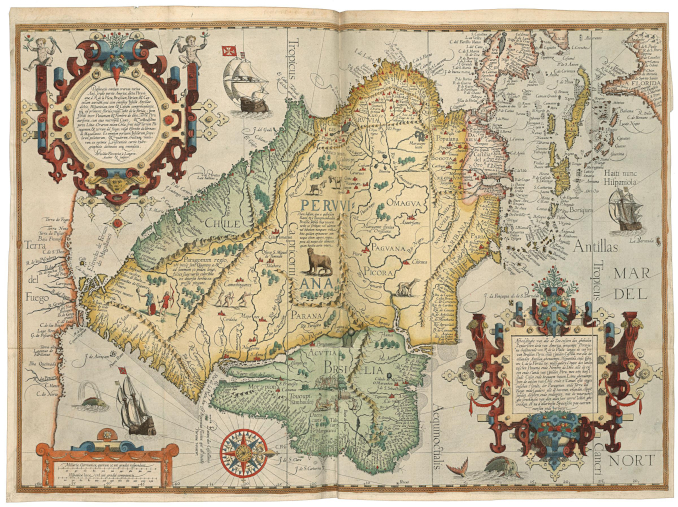

While there would also have been political and religious reasons for Spain to search for new territories, the main motivation at the time was the search for access to India and its riches. The Spaniards did not find a route to India (that was achieved almost at the same time by the Portuguese), but they certainly found a new, enormous source of global trade.

The saying that “money does not buy happiness” is certainly applicable here. Finding in 1545 the world’s richest silver mines in Potosí (in today’s Bolivia) did not bring anything but misery to the native population enslaved in the mines and, paradoxically, brought much less wealth to Spain than expected. The Potosí mines yielded an enormous amount of precious metal, but if the bullion got to Spain at all (given the decimation of shipments by pirates and storms, and the diversion of almost one-third of production to Portuguese merchants through illegal trade), the silver would almost immediately flow back out to Dutch merchants, financing trade with India or China. Spanish silver reals also serviced the crown’s enormous debts drawn to fund religious wars and the Spanish Armada, so famously destroyed in 1588 by Elizabeth I’s fleet. Spanish King Philip II (in power between 1556-1598) went bankrupt three times while reigning over the largest landmass that included Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, today’s Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, parts of South America, and lands in North Africa and Asia.

This “pieces of eight” silver coin materially documents the precious metals drain performed by the Spanish conquerors in South America. Once the mines were developed, the silver coins were minted in situ, to be shipped worldwide—to Spain for the royal treasury but also for use in the Asia trade. The Qing dynasty court in China was happy to trade precious porcelains and silks to Europe, but they demanded payment exclusively in silver, refusing any European trade goods as “not needed.” Some of the silver that made it to Spain also flowed out of the treasury for extravagant constructions like the Escorial palace. Between trade, costly projects, and the servicing of the country’s war debts during the reign of several kings, little was ever invested.

Silver and gold could ignite the imagination of any 16th-century adventurer, but ironically, some of the most lasting gifts of the Americas to the rest of the world were new kinds of perishables. The two examples of vegetables that became staples in Europe were potatoes and tomatoes.

Potatoes—brought by the conquistadors to Europe—at first were only used as cattle food, until the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and subsequent famine changed the view that potatoes were not fit for human consumption. In the 18th century, they were introduced to French cuisine. Various famines throughout Britain and Europe in the late 18th to 19th centuries further spurred potato farming on. By the 19th century when van Gogh painted this Still Life with an Earthen Bowl and Potatoes and other “portraits” of the humble vegetable, they had become a daily food, especially in the countryside.

Tomatoes also took time to become accepted as a source of nourishment in the Old World. At first, people were suspicious of the new red fruit, originally considered more decorative than edible. By the 18th century, however, tomatoes had entered into cooking recipes, especially in the Mediterranean region where the plants thrived. Tomatoes were also very picturesque, with their vivid red and orange hue and bulbous shapes, so they began to be included in still lifes, and especially in Italian paintings and Spanish bodegones (a genre of kitchen-themed paintings of food, game, and pottery).

Louis Meléndez specialized in those paintings, raising humble vegetables and wooden bowls to the status of precious objects with his precision of line and vivid colors. This 18th-century artist from Madrid lived close to the royal court but despite his talent was unable to succeed there. He tried twice to liberate himself from the tedium of painting such still lifes, applying for a position as court painter, which would have allowed him to get important portrait commissions and secure a steady income. He failed to obtain the position, and he eventually died in poverty. His bodegones, including the particularly charming Still Life with Cucumbers and Tomatoes shown above, are now prize possessions of the Prado.

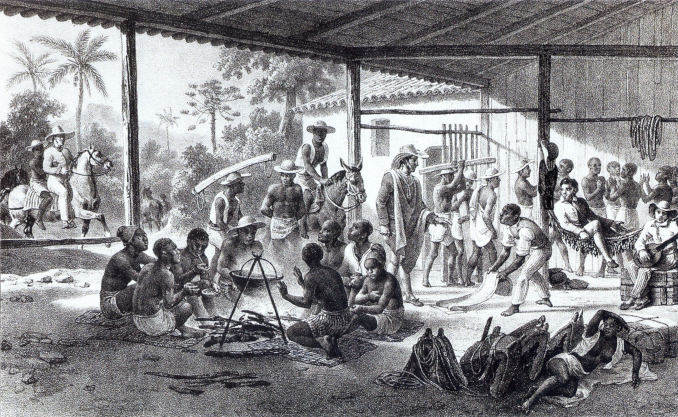

In order to produce and ship all the outflow of the New World’s goods—sugar, tobacco, spices, cotton, timber, coffee, etc.—early plantation and mill owners adopted a millennia-old solution: slavery. Practiced since antiquity, often as a punishment of enemies, it flourished in the Americas to a horrifying extent hitherto unknown. The demand for labor created by the discovery of a new source of trade fueled large-scale enslavement of local populations as well as the infamous ships from Africa.

The subject of the African slave trade is too vast for the scope of this story, but as the backbone of trade with the Americas, it was also sometimes a focus of art. Unsurprisingly, though, there aren’t many artworks created during the slavery periods in either of the Americas that illustrate the scale of that trade. Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802-1858) was one of the few artists who did. He traveled throughout Brazil between 1822-1825 as part of an expedition, later visiting many parts of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Bolivia. Aside from being an accomplished artist, he was also an ethnographer who would meet, study, and draw people he met in his travels—native farmers, Portuguese or Spanish landowners, city dwellers of all social classes, and slaves. This detailed illustration from 1830 documents a moment in the slaves’ life. Rugendas’ artworks were typical for the era in their romanticizing views of local people and their lives, but he held abolitionist views.

The Lackawanna Valley painted by George Inness in the mid-19th century is a popular example of North American technological expansion and modernization, and it is featured here for the same reason. This view of northwestern Pennsylvania depicted the location of a new company called Delaware and Lackawanna Railroad Company. Its president commissioned Inness to immortalize the round depot, the railroads, and the company’s new engines. The artist’s first attempt did not feature a sufficient amount of engine traffic and was rejected. This final panorama has numerous pillars of steam rising throughout and offers a view of the central, imposing rotunda building. Originally, the railroad company commissioned this painting and others like it as sort of an early advertising effort, counterbalancing some protests against the rapid industrialization. The company sought fine art’s ennobling of the new enterprise. Inness, however, seems to have been more interested in conveying the valley’s beauty than expressing his admiration for the advent of technology. Perhaps his point of view is best expressed through the small figure in the foreground—a man in a straw hat who is gazing across the stumps of freshly cut down forest onto the rolling land. The central part of the land is already devoid of trees and grass, replaced by train tracks, wide roads, and new buildings, with the implication being that this bucolic valley view will soon disappear. A few short decades after Inness created this painting, unstoppable industrialization would make that part of the two continents the biggest player in global trade and commerce.