Food for the Soul: Napoleon’s Loot

Ridley Scott, the man who over half a century has given us Gladiator, Alien, Blade Runner, and The Martian, has not stopped making big movies. His latest is Napoleon—you do not get any grander than that in terms of subject matter. It is an ambitious biography of the emperor’s rise to power, his many battles, and his apparent obsession with Josephine. However, this being a movie where an English director directs an American actor (Joaquin Phoenix), the film has already garnered some negative reviews. Not surprisingly, it has been panned in France, and it is indeed flawed by some historical inaccuracies, the strange casting of an older, tall actor with a brooding countenance to portray a young, small Frenchman, and an Anglo-Saxon point of view on both the emperor and French history. On the other hand, the French film industry has produced few major Napoleon pictures since Abel Gance’s silent film from 1927 and Sacha Guitry’s biopic in 1951, so perhaps Ridley Scott’s movie will have to do for contemporary generations.

The movie’s release is perhaps an excellent occasion to highlight Napoleon’s ambiguous role in spreading knowledge of art in 18th-century Europe. Thanks to the emperor’s “importation“ of artworks from all over Europe and Egypt, numerous artists, scientists, and the French general public learned about Italian and Flemish art, while a new science of Egyptology was launched. At the same time, history has never seen art plundering at the scale inaugurated by the Napoleonic armies.

In Scott’s movie, there is a controversial scene where Napoleon orders his artillerymen to bombard Egyptian pyramids. In reality, the French army never aimed cannons at these monuments. On the contrary, Napoleon brought to his Egyptian campaign a 160-person-strong group of civilians: scientists to study Egyptian artifacts; draftsmen, sculptors, and painters to record archeological discoveries; and historians and linguists to study hieroglyphs and artifacts. Thanks to this effort, the new science of Egyptology was created, even though the pioneering excavations and collection of artifacts would often damage the findings, not to mention destroy the context in which the items were found. The late 18th century (the Age of Enlightenment) was focused on finding out new things but not necessarily on painstaking preservation—something that became a domain of pedantic German and English academicians in the next century.

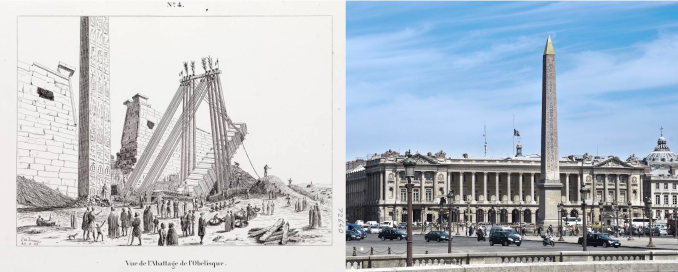

Napoleon himself was most focused on public relations—that is, on promoting his campaigns, his military successes, his reshaping of French society in the aftermath of the revolution, and, of course, his own heroic personal image of an emperor scaled to compare with the most famous Roman leaders of antiquity. As any ruler from the Roman Caesars to Soviet leaders knew well, art is indispensable to propaganda. You either make grand art or you appropriate it. Napoleon did both. From Egypt, he would transport obelisks and other carved stones, including the most famous of them all—the Rosetta Stone. Starting with his conquest of Italy (1796-1797) and continuing during his Egyptian campaign (1798-1801) and throughout his career, he would also encourage artworks that emphasized his heroic looks and deeds, regardless of the actual circumstances.

A perfect example of art providing a glossed-over version of events is a painting called Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims in Jaffa, in which he is portrayed as a benevolent leader bringing comfort to the stricken troops. In reality, Napoleon ordered the poisoning of about 50 infected soldiers in an effort to limit the epidemic. The artist who painted this picture, Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), was a young artist who painted an early heroic picture of Napoleon during the Italian campaign and remained his eulogist throughout the leader’s reign.

If Egypt provided the most monumental artworks for Napoleon, Italy was the source of the most sophisticated ones to satisfy the emperor’s collection fever. By Napoleon’s time, the custom of victorious armies appropriating valuables (including bronze statues that would be melted down for cannons) was already an old European tradition, but the post-revolutionary French Directory formalized the process by establishing a body with the unwieldy name of “Government Commission for the Search of Scientific and Artistic Objects in Countries Conquered by the Armies of the French Republic.” Thus went into operation a formal channel for the seizing and sending to France of wartime booty. As Napoleon’s correspondence attests, instead of “making war finance itself, the Directory proceeded to make war for the purposes of finance.” Napoleon further systematized the acquisitions by inserting clauses into peace treaties that ensured that conquered cities would provide artworks as part of the levy.

For example, the ransom extracted by Napoleon from Italy was presented to various Italian duchies as the price of liberation from the Austrian occupants. The scale of the plunder was enormous. In May 1796 alone, Bonaparte collected two million francs’ worth of jewelry and silver, to be followed one month later by two million francs in gold bullion. Flush with cash, Napoleon could ensure the loyalty of his troops. Thanks to his seizures of art, like Mantegna’s Madonna della Victoria plundered from Veneto in 1798, his backers in Paris could also see the evident benefits of the French army “liberating” the faraway lands.

Then and now, the biggest treasure trove in Italy was at the Vatican, so the Commission demanded that Napoleon seize from Rome 100 art objects, 500 manuscripts, and 83 statues—including the statues of Apollo Belvedere and the Laocoön Group—as well as The Transfiguration, Raphael’s last painting.

The newly established Museum of Louvre was now stocked with innumerable masterpieces. To hundreds of collections confiscated from the French aristocracy during the revolution, Napoleon’s army added the spoils of its Italian plunder. The French public as well as artists and intellectuals were now able to peruse the “best of the best” of Italian Renaissance and Greco-Roman statuary. Because scientific research did not match the pace of acquisition, the priceless artworks sometimes piled up in the galleries. A strange fantasy painting by Hubert Robert (1733-1808) called Imaginary View of the Grande Gallerie of the Louvre in Ruins shows Apollo Belvedere inside the Louvre, with some statues stacked as if in the warehouse that the early Louvre had indeed become. This sculpture, together with many other seized artworks, was eventually returned to Italy. There is one huge and incredibly important painting, however, that has never been back, attesting to the plundering passion of both Napoleon and the Directory government.

In 1563, Paolo Veronese (1528-1588), a Venetian whose skill at using colors was outstanding even in the crowded field of the Italian Renaissance’s artistic giants, painted The Wedding Feast at Cana. Commissioned by Benedictine monks for their refectory at San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, it featured at Jesus’s table the most important personages known to the Venetian society of the mid-16th century—the powerful rulers of France and the Holy Roman Empire, queens Eleanor of Austria and Mary I of England, Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottomans, as well as Veronese himself, flanked by the artists Jacopo Bassano, Titian, and Tintoretto.

That painting, together with 15 others (including three other Veronese canvases, as well as two Titians, a Tintoretto, and a Bellini) found itself on a list drafted by Claude-Louis Berthollet, an eminent doctor and chemist who as a Commissioner came to Venice to pick the best paintings for shipping to Paris. Despite the protests of the Venetians, the paintings left in August 1797 on an arduous journey to France. Veronese’s Wedding Feast painting has never been returned. In fact, out of 506 paintings seized in Italy by the Napoleonic army and the Commission, 248 remain in France.

The Wedding Feast at Cana is now located in the same Louvre hall as the Mona Lisa, although the monumental Veronese canvas (22 x 30 feet, 677 x 944 cm) is often ignored by the many tourists who are instead in pursuit of the ultimate Instagram prize of La Gioconda. The latter, in reality, is hard to see, being a smallish painting, almost invisible in a glass enclosure and separated from viewers by ropes and long lines.

There is one spectacular Napoleonic seizure that managed to return to Italy. The four copper horses atop the Venetian Basilica of St. Marks have been the most desirable prize for centuries. Created in the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD, they had been adorning a hippodrome in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul) until a Venetian doge looted the city in 1204. Over five centuries later, the magnificent statues were kidnapped again. In December 1797, Napoleon personally demanded that his chief of staff ensure the prompt shipping of the horses from Venice; they were placed at the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in the center of Paris. After Napoleon’s empire fell in 1814, the Treaty of Paris returned Venice to Austrian-governed lands. In the aftermath of Napoleon’s Waterloo defeat, the Austrian emperor ordered the horses to be taken down and sent back to Venice. The current foursome of horses atop the Arc de Triomphe is just a copy of the Venetian quadriga, while the original statues of the horses reside once again in Venice.

Napoleon’s reign lasted only a couple of decades at the turn of the 19th century. Much more lasting was his legacy of redrawing the political map of Europe, the administrative unification of small principalities in territories of future Germany, Italy, or Austria, and his introduction of a codified legal system that remains the basis of numerous European justice systems to the present day. In art, Napoleon’s zeal as a military conqueror and mega-collector of cultural treasures had even more lasting consequences—both good and bad. Egyptology might not have been born when it was, and the Rosetta Stone might never have been discovered. But some masterpieces, like The Wedding Feast at Cana, might not be at the Louvre.