Food for the Soul: Poets and Lovers – Vincent van Gogh Exhibition in London

“The starry sky at last, actually painted at night, under a gas-lamp.”

~ Vincent van Gogh in 1888

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

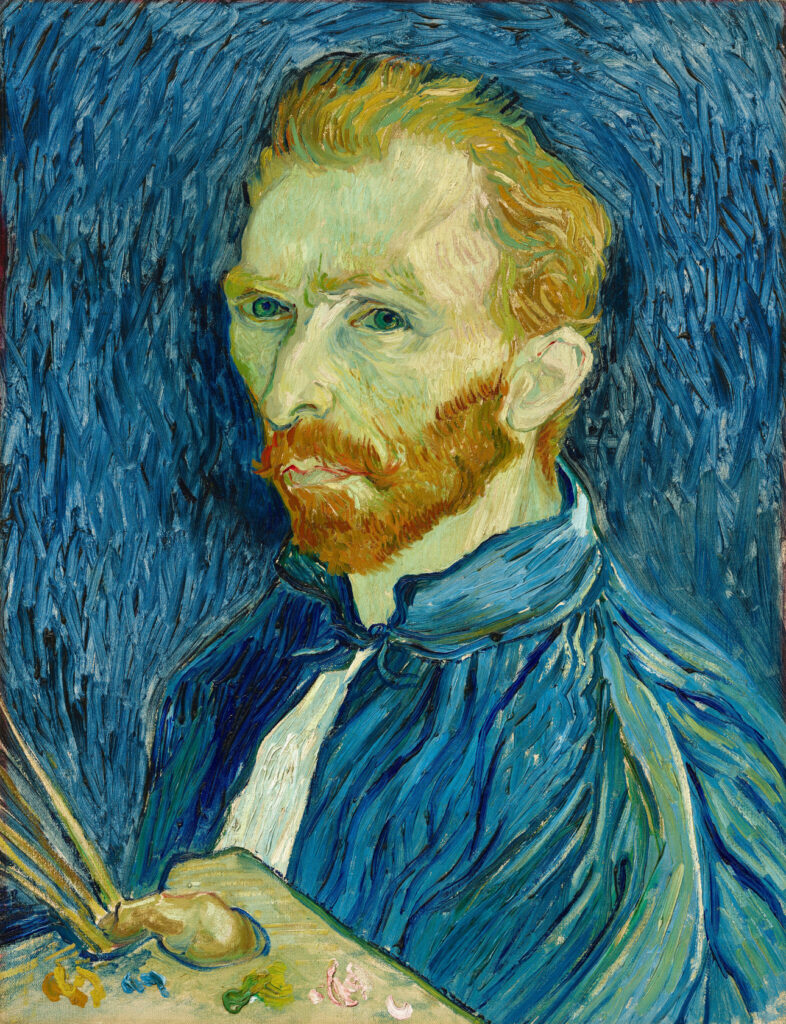

As part of the celebration of its 200th anniversary, the National Gallery in London has just opened an exhibition titled Vincent van Gogh: Poets and Lovers. Despite the short span of his career, van Gogh was a prolific artist, with his last two years of painting being the most fruitful. It is that period in van Gogh’s art—the time in his life when his creativity was at its most frenetic and advanced—that is the focus of the exhibition.

The “Poets and Lovers” in the exhibition title refer to the artist’s idea of making room decorations that would show both poetic and romantic images, as well as to the themes he wanted to explore in his landscapes and portraits intended for exhibitions. He found models for his portraits of a “poet” and a “lover” in two acquaintances. Eugène Boch, a Belgian Impressionist, served as the model for a poet (van Gogh thought that Boch’s gaunt face was reminiscent of Dante’s), while a soldier named Paul-Eugène Milliet, who was also known as a local lothario, was his model for a lover.

On arrival in Arles in 1888, van Gogh started setting up his “yellow house,” not only as his own studio but also as a future location for an artists’ center, where he hoped to invite Émile Bernard, Paul Gauguin, and other artists. To this end, he started to create “decorations”—that is, paintings that would evoke creative moods such as “happiness,” “poetry,” and “love,” and which would transform the modest rental space into a creative studio for him and other artists. Although his plans dissolved after a quarrel with Gauguin and the violent episode of a self-inflicted wound, “poetically-themed” canvases remain a large part of the artist’s legacy.

For the room he was preparing for Gauguin, and later as an idea for a display at a Salon exhibition, he conceived an arrangement of three canvases: a portrait of a local mother, Augustine Roulin, flanked by two paintings of sunflowers. Augustine is shown holding a string that would have been attached to a cradle, hence the title of this painting: La Berceuse (Eng.: “lullaby” as well as “woman rocking a cradle”). There are five versions of this picture; the London exhibition uses the one from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The Sunflowers need no introduction, with both of these versions being some of the most popular images on the planet. Kudos to National Gallery for assembling those three pictures as the artist had intended—for the first time since they were created. The version of Sunflowers on the left is the one that the National Gallery acquired exactly 100 years ago, so the museum is celebrating two anniversaries at the same time: this acquisition and the 200 years since the gallery’s opening.

POETS’ GARDENS

As eternally fascinating as the enormous sunflowers are, their iconic popularity is actually a kind of distraction at this exhibition, which showcases so many exquisite landscapes. Some of the landscapes are little known because they come from private collections, and other pictures—loaned by galleries all over the world—have not been assembled before. Thanks to those loans, the exhibition is full of canvases from van Gogh’s most robust and mature period; the full force of his unique talent is evidenced by works that have a beauty undiminished by the 150 years of new art created since his time.

In those pictures, the artist explored the poetic meanings and emotional impact of arrangements of lines and planes of color. He did it quite deliberately, referencing poetry, literature, and his dreams, as well as incorporating studies of color theory. When he tried to explain the meaning of his painting titled Memory of the Garden at Etten, he wrote to his sister Willemien: “I don’t know if you’ll understand that one can speak poetry just by arranging colors well, just as one can say comforting things in music.” This is probably one of the great discoveries of this exhibition, which shows how much van Gogh’s art is a result of his educated and sustained search for a modern language of artistic expression. The exhibition reveals the effort he put into perfecting the emotional impact of color and style, and how much his art is the product of a sophisticated exploration of motifs, symbols, and color relationships. The old idea of van Gogh as a mad artist (even if he created some of his art during bouts of what today might possibly be diagnosed as bipolar hyperactivity) is replaced here with a panorama of his recurrent themes, beautiful color arrangements, and truly genius transformations of ordinary reality—such as a wheat field, a hospital courtyard, or an olive grove—into an orgy of colors and shapes, all of it studied, sketched, researched, and calculated for the best artistic and critical results.

OLIVE GROVES

In a letter to his brother Theo in 1889, van Gogh wrote, “On the other hand the olive trees are very characteristic, and I am struggling to capture that. It’s silver, sometimes more blue, sometimes greenish, bronzed, whitening on ground that is yellow, pink, purplish or orangeish to dull red ochre. But very difficult, very difficult. But that suits me and attracts me to work fully in gold or silver. And one day perhaps I’ll do a personal impression of it, the way the sunflowers are for yellows.”

As much as sunflowers and cypresses are some of van Gogh’s trademark images, olive trees were equally important in his artistic language. Only when he arrived in Provence, after spending most of his life in the cold climates of the Netherlands and Paris, would he discover the painterly shapes of gnarled olive trees that fit so well into the sinuous style of his landscapes. He really started focusing on them when he committed himself voluntarily to an asylum in Saint-Rémy where he stayed for a year, often looking over a low wall at the surrounding hills and olive groves.

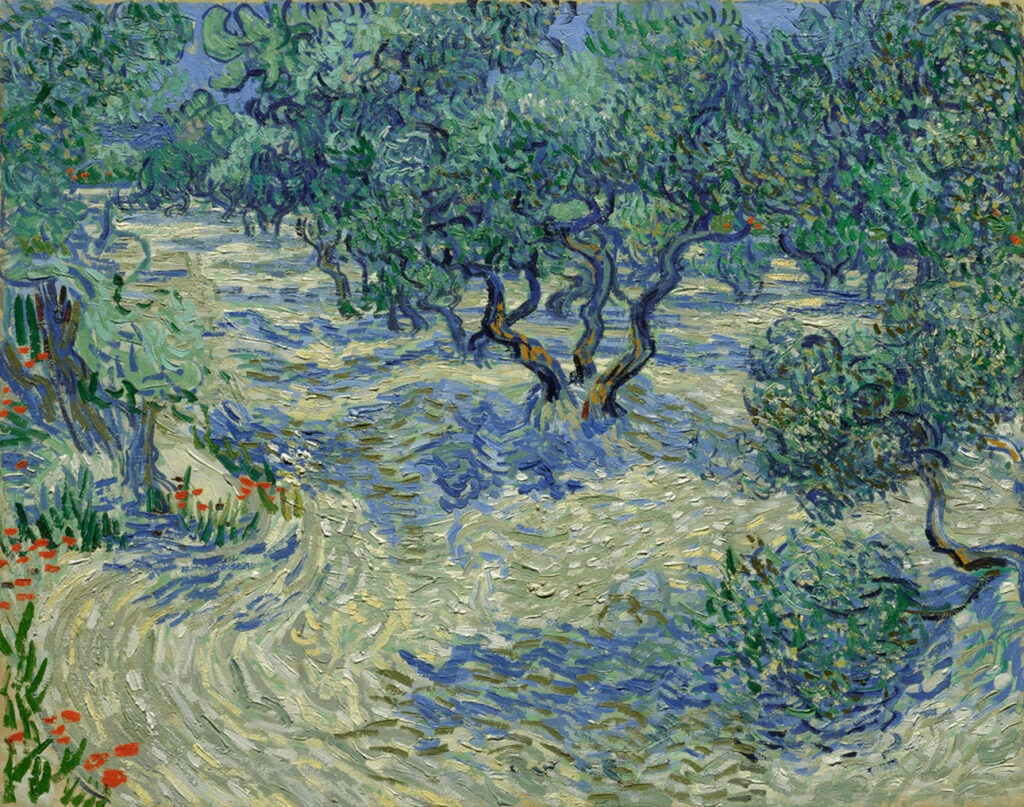

His adventures with color, started in Arles when he painted his lodging all yellow and his models green-faced, continued with the olive trees at Saint-Rémy. The painting called simply Olive Grove (1889, Gotheburg) features multicolored trees in the middle, but the orange ochre clay of the earth is repeated in splotches in the sky, uniting the top and bottom in the same color scheme.

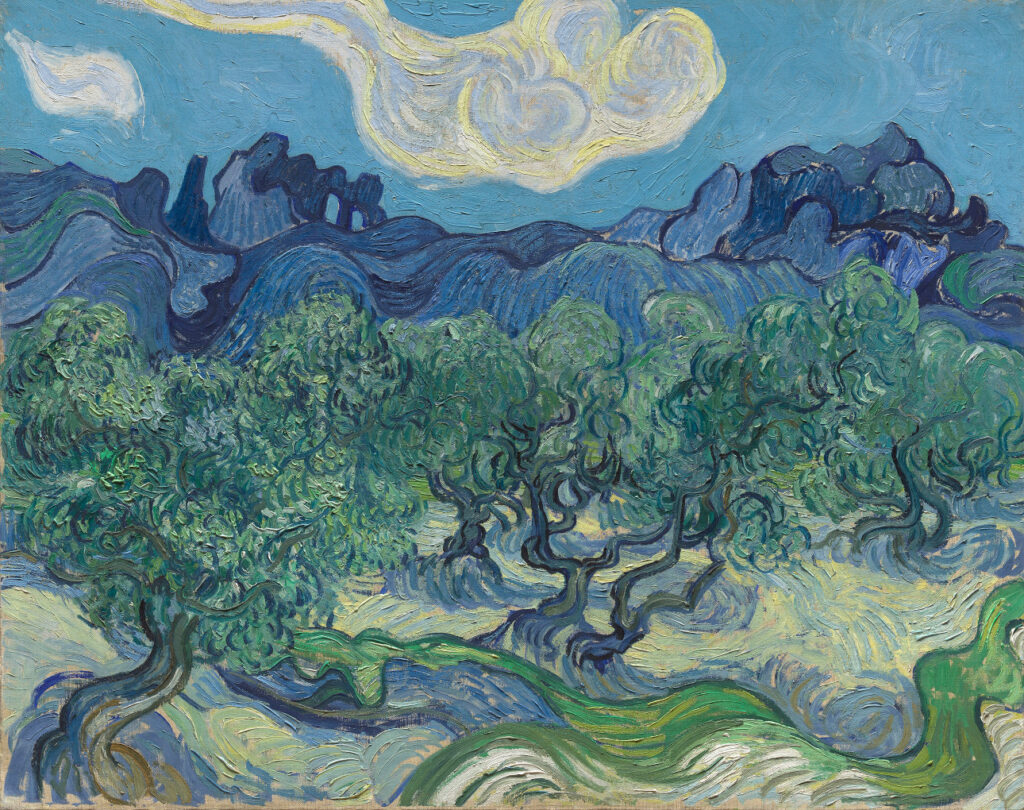

In the painting The Olive Trees (1889, MOMA), he would repeat the undulating shapes of olive tree trunks and branches in the shapes of the clouds above. Just as in the previous painting, the synergy of nature is complete—“as above, so below,” to quote the ancient Hermetic texts.

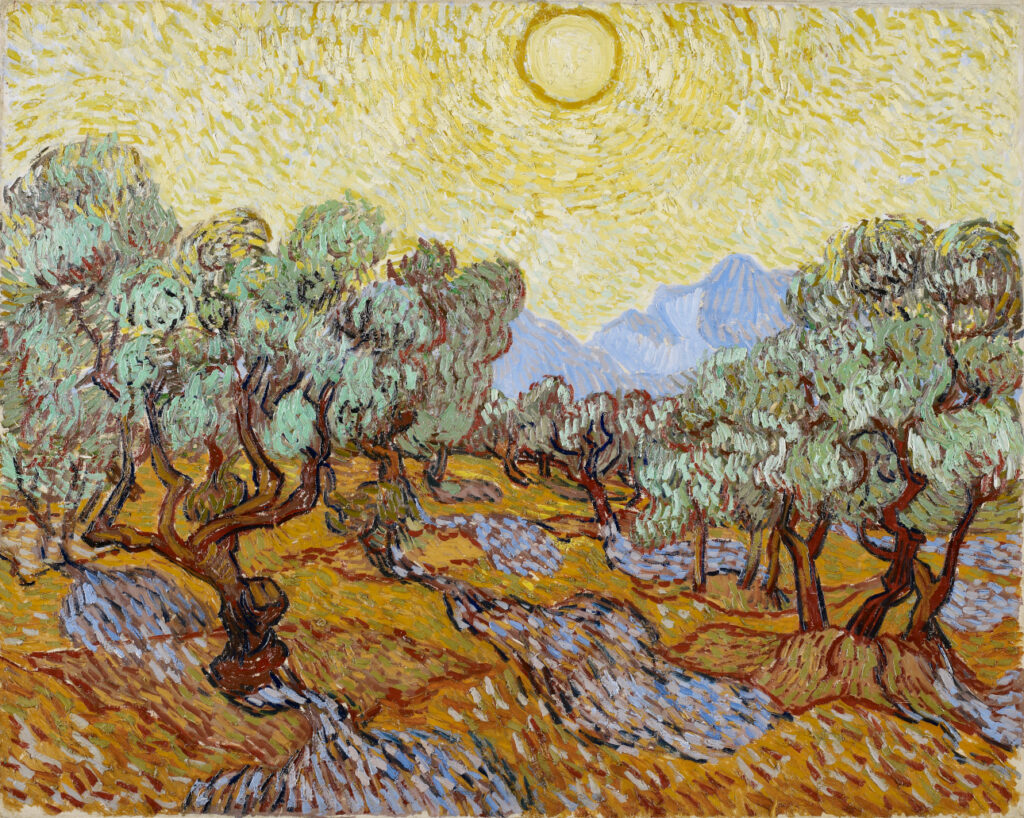

In another view of Olive Trees (1889, Minneapolis Institute of Art), the gnarled trees in sloping earth are beaten by a huge, intense sun that covers the entire sky with its rays. This picture is much more than a color study, that painterly issue that so preoccupied the artist. There are almost religious overtones (so natural for a man who once tried to be a missionary), and the emotional expression is that of a struggle against a merciless force rather than just a fascination with the twisted shapes of exotic-looking trees.

Whether he turned his eye toward flowers, trees, or just the night sky, van Gogh’s preoccupation with color, his love of visual drama, and his artistic sensibility predated by decades all of the Expressionists, Fauvists, and Cubists who later dipped heavily into the fountain of his visions. Moreover, this landmark exhibition highlights the fact that, despite the popular view of van Gogh as a mad genius who slashed paint on his canvases in a frenzy, this was a sophisticated artist who studied theories, techniques, and other artists; planned his themes, cycles, and compositions; drew numerous studies; and only then would embark on creating his unique images.

The exhibition Vincent van Gogh: Poets and Lovers runs from September 14, 2024 until January 19, 2025 at the National Gallery in London.