Food for the Soul: For the Love of Books

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

In the United States, but not so much in Europe, you can sometimes walk into a beautiful house decorated with paintings and knickknacks but with no books anywhere to be found. The advent of digital media in the form of audiobooks and Kindle readers has accelerated the disappearance of physical books. Bookstores have dwindled to just a few independent stores and chains where, often, there are more toys and stationary than things to read. The specter of centuries-old intellectual intolerance, well-known from Nazi Germany, is raising its head as well, allowing for the banning or destruction of books in many places in the world. In some countries, the Covid pandemic diminished children’s literacy. Once the Baby Boomer generation disappears, future generations will feel less need to surround themselves with paper volumes, perhaps just making the occasional exception for a coffee table decoration.

Mankind’s love affair with written-down words seems to have gone through a long arc. Its heyday was perhaps at the Library of Alexandria, which around 100 BC boasted a collection of several hundred thousand books—all of which disappeared when the library was burned, first by Julius Caesar in 48 AD, and then when its remnants were destroyed between 270-275 AD. Conversely, in the present day, bookstores have been replaced with stores that make most of their profits from coffee and toys, and the changing role of public libraries means that they now often serve primarily as shelter for the dispossessed and those who don’t have access to a computer.

For most of the history of the written word, women’s ability to read and write lagged behind male literacy; however, in every period and place, there were some learned females. This fresco found in Pompeii most likely represents Sappho, the celebrated Greek poet from the 6th century BC. The society of ancient Rome did not lack for educated women—from the first ladies of the Republic and then the Empire to the many educated slaves who arrived in Rome as prisoners of war. The woman in the fresco is not holding a book but a wax tablet and a stylus (which is to say, writing implements), but where there is writing, there is, of course, also reading. Roman books were written on scrolls, so they would have looked different from contemporary books; still, there would have been collections of scrolls in temples, official buildings, libraries, and private homes. The vast collections of such books—written by Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, or Roman authors—mostly disappeared with the destruction of the Roman Empire.

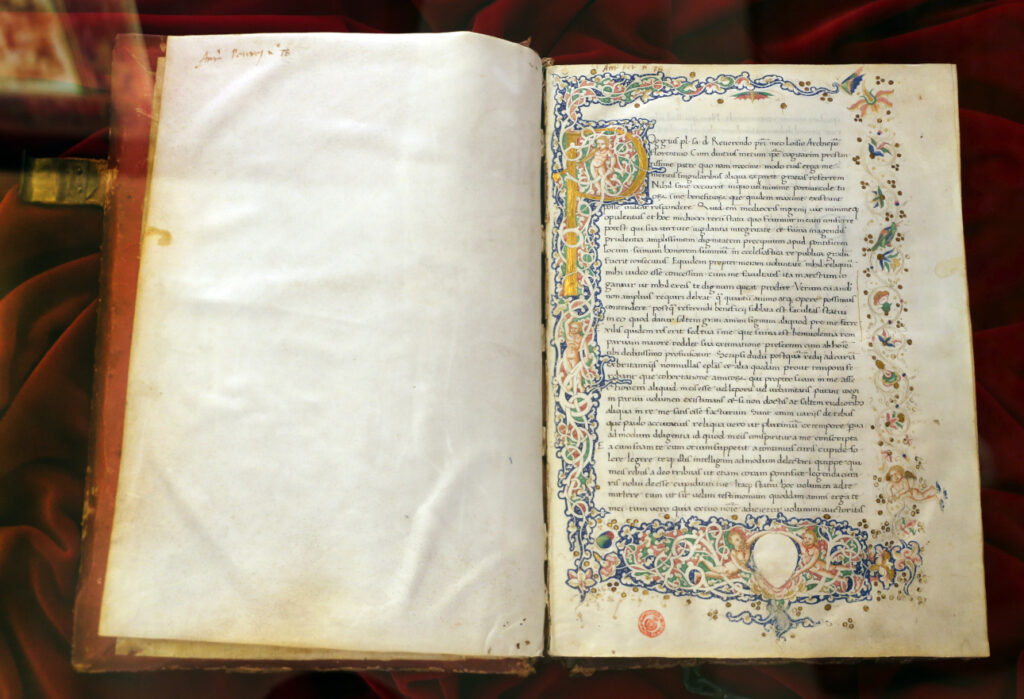

Some books from antiquity survived in monasteries. Religious orders such as the Benedictines had as their monastic rule the requirement of reading, which in turn called for the preservation of parchment scrolls. Consequently, there was a need to teach reading and writing to all monks, and older books had to be laboriously copied if they began to fall apart. Although the content of antiquity’s writers may have been mostly lost, Renaissance book hunters like Poggio Bracciolini, who brought Lucretius back from oblivion, later rediscovered some of them.

In Christianity, two of the most frequent depictions of books in artworks were the volumes shown either as an attribute of St. Jerome or as the Virgin Mary’s reading material in scenes of the Annunciation. Countless artists and church decorators created those images for centuries.

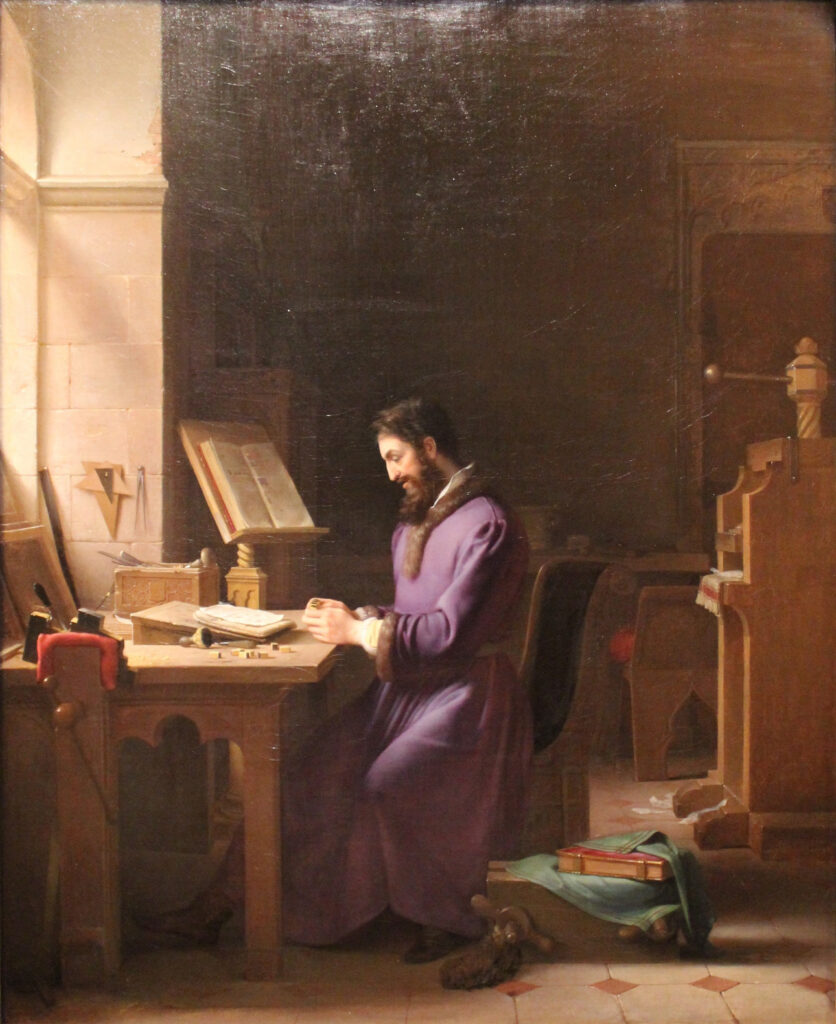

The historical St. Jerome was a Dalmatian convert to Christianity, living in Rome, Antioch, and Jerusalem in the 4th and 5th centuries. During his ascetic retreat in the Syrian desert, he learned Hebrew and starting translating the Old Testament. His translation of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin (the so-called Vulgate version) earned him later canonization as a Catholic saint. In art, he is usually portrayed as a hermit, living in the desert and accompanied by a tame lion—he is said to have liberated a desert lion’s paw from a thorn, resulting in the wild cat’s gratitude and companionship in the wilderness. The saint is also often shown either studying books or writing, in reference to his scholarly pursuits. St. Jerome in the Desert, painted by Giovanni Bellini in the early Renaissance, includes the saint’s attributes of both the lion and the book to make his identification easy for viewers. However, unlike the typical serious representation of a studious saint and his lion lying down like a faithful dog, here we have St. Jerome preaching the gospel to an attentive big cat. The power of the sacred words is not lost even on a wild beast.

A typical painting of the Annunciation would have the archangel Gabriel, spreading his multicolored and enormous wings, alight in front of a startled Virgin Mary who learns that she has been chosen to bear the Son of God. In famous paintings by da Vinci, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, or van Eyck, this is the scene that illustrates the story. Lorenzo Costa the Younger was a minor Renaissance painter, working mainly as a court painter in the artistically refined Mantuan court of Francesco Gonzaga. Costa’s Annunciation, painted around 1510, is instead a very “modern” rendition of the theme. The messenger is not a winged angel but a divine dove, and Mary is sitting with a book in her lap in a natural pose that anybody might assume when sitting on the floor. What is lacking entirely in this painting is the traditional setting of richly appointed rooms, furnished like any chamber of a grand Italian lady. Other paintings by Costa, almost all of them religious, are composed more traditionally, but this Annunciation is very different. This painting is more about the woman, engrossed in her reading, and the picture is devoid of any superfluous imagery. It’s just her, the book, and a symbol of divine grace.

Even if in China books had been printed for centuries, the way to create multiple faithful copies of the same image or text did not arrive in Europe until around 1450, when Gutenberg’s new technology changed Europe. The printing press enabled increased literacy and fast communication of ideas (which led to the Reformation and the birth of Protestantism) and created access to education for women (who were not allowed to attend schools and universities but could finally study at home), and it wrenched from the Church the monopoly on book writing, reading, and collecting. Sometimes, reading even became forbidden fruit. One such instance is illustrated in a popular 19th-century picture, The Forbidden Reading, by Belgian academic painter Karel Ooms.

This is a picture probably much better known to Protestants than Catholics. When this academic 19th-century painter created his vision of the life of early Protestants living in Catholic Antwerp in the 1600s, he could not have anticipated that his dramatic painting would become a much-reproduced icon of Protestant persecution during the Reformation wars. What is forbidden here is the act of reading the Bible in the local language. A resurgence of persecution of the small Protestant community in Catholic Belgium prompted this painting to gain popularity—it was reproduced for Protestant homes and copied by other painters. Ooms was clearly interested in the theme of persecution, because he also painted a similar composition of a startled couple titled The Jews in the Middle Ages.

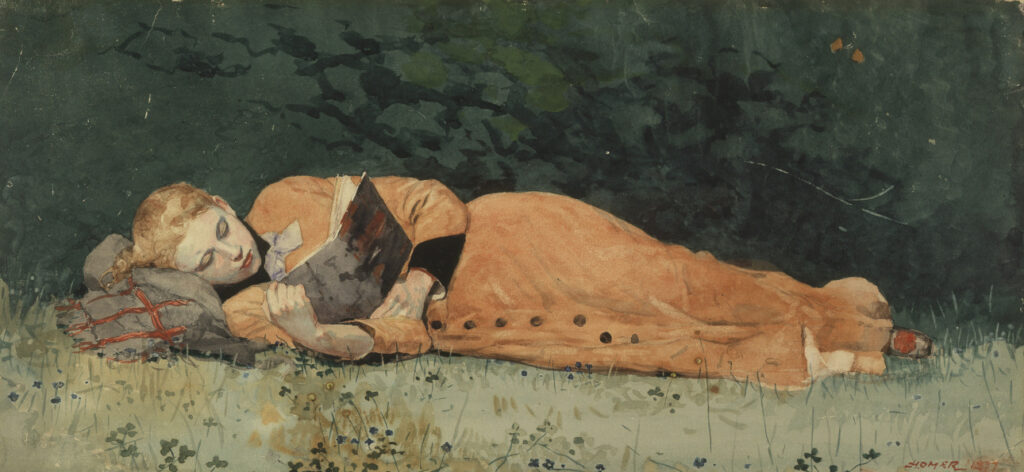

In centuries past, books were not only needed for education, commerce, exchange of ideas, and commemoration of events; they were also an indispensable companion—to kill time, to provide entertainment, to avoid an awkward conversation, or to find a pretext to sit somewhere alone. As such, they also found their way into paintings, mostly of young women who would often use books as an excuse to escape either boredom or an unwanted companion. Winslow Homer’s image of a young woman engrossed in a book, which he titled The New Novel, is a picture of the typical occupation of a 19th-century woman. With the exception of women who had to work (peasants, factory workers, servants), there was a vast group of women for whom reading was one of the few acceptable occupations. Because middle- and upper-class women did not work (either they did not have to or they were not permitted to by men in their families), their days were often filled with doing crafts, making music, reading, and letter or diary writing.

Reading books to escape boredom was not a pastime limited to Western societies. Here is a charming Japanese print by one of the masters of ukiyo-e woodblocks, Utagawa Kuniyoshi. The title says it all: Feeling Like Reading the Next Volume. It shows a lady who is clutching to her chest a book in a gesture familiar in all cultures—it’s the protective gesture of keeping a newfound treasure. In this case, the treasure is a new book, and she is gripping it in the same way we might clutch a newly purchased vinyl, CD, or DVD—and these days, perhaps even a newly acquired art print. The problem is that technology has changed so much that we have fewer and fewer physical objects to clutch. It’s hard to get excited about a download link or an audiobook.

I still love the smell of a new book, especially an art album, but I am in an ever-shrinking minority of people who like the physicality of paper, the whiff of print ink, and the joy of turning pages. These days, ironically, there is a bit of snobbery about collecting books; dating apps favor postings of “men reading books” and Zoom meetings look better with a wall of books behind the participants. But does this reflect a genuine love of books? Reading physical books seems to be sliding into the realm of an old-fashioned hobby, like making jam or stamp collecting. We still read, thankfully, but fewer books are made of paper and ink. It seems such a pity that this tactile pleasure is fading away.

But all hope is not gone. Recently, the small town of Chelsea near Detroit, MI participated in a very visible act of loving books. A local bookstore, appropriately named Serendipity Books, was changing locations, and they needed to move stock. About 300 residents of this small community formed a human chain in the streets, passing each book by hand. They moved 9,100 volumes in two hours (much less time than it would take to box the books and use a truck), and the whole operation revived residents’ sense of community as well as confirming their interest in the books offered by this local bookstore.