Food for the Soul: Paris Fashion 2025

By Nina Heyn

If it is spring in Paris, fashion is an obvious theme, but in the world of art, this means something more sophisticated than a runway at a designer house. Three major Paris museums have riffed on the theme of fashion in a manner reflecting these museums’ style and collections.

House of Worth

In partnership with the Palais Galliera fashion museum, the Petit Palais (an elegant place right off the Champs-Elysées) has mounted a very well-received exhibition that showcases the achievements of the father of haute couture—a man named Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895), whose House of Worth was the place to go for the rich and famous in France, England, or the United States. To have a gown from Worth was as much as a coup for a bride in 1900 as it is now to order a dress from Dior or Dolce & Gabbana.

Worth pioneered the idea of haute couture—the creation of expensive, unique dresses and accessories that would be either custom-designed for a single client or, later, available through mail catalogs for international clients. The House of Worth developed various business strategies still widely used today, such as cultivating celebrity clients (often royalty), patenting their designs, and creating and selling branded accessories in department stores. In the same way that a modern fashionista might covet a designer purse, a fashionable (and affluent) English or American lady in the 1880s would order the latest models from Worth in Paris. Although the fashion powerhouse built by Frederick Worth was subsequently run by his sons and grandsons all the way to the 1950s, its heyday was at the turn of the century.

Here is the same dress in a fashion photo, worn by an aristocrat who ordered the gown in the late 1880s:

At the beginning, Worth’s clients were concentrated among the aristocracy (including the famous empresses: Sissi of Austria and Eugénie of France) and the new class of the grande bourgeoisie—industrialists, bankers, and merchants. Thanks to the ubiquity of photography in the last quarter of the 19th century, we can compare the actual dress, one of the many preserved in the Galliera collection, with a photo of its owner, Countess Greffulhe, who posed in this gown in 1886. The faded black-and-white archival photos come to life at this exhibition when the actual gowns are displayed, refreshed, and presented in their original splendor.

Here is a detail of the muslin flowers that decorated this deceptively simple satin cape:

The exhibition traces the development of fashion, from opera gowns through elaborate evening capes and ballgowns with trains, culminating in a collection of flapper dresses that replaced long gowns after WWI.

By the 1930s, the House of Worth was being managed by the third generation of the family. Titled and famous personages like the wife of Prince Aga Khan and the British royalty were still the clients, but the company also expanded into mass production of perfumes and accessories, as well as clothes that were ready-made and available through catalogs.

The Worth: Inventing haute couture exhibition of over 400 works runs from May 7 through September 7, 2025 at the Petit Palais in Paris.

The Golden Thread

The anthropological museum, Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, is celebrating the art of fabric with an exhibition called Golden Thread: The Art of Dressing from North Africa to the Far East. Branly’s vast collection of historical clothing and techniques of manufacturing gold thread and ornamentation is showcased next to historical clothes and fabrics as well as select golden attires from Guo Pei, the Chinese designer with an extraordinary scope of work, presented alongside other gold-inspired haute couture creations.

Guo Pei’s gowns from the early 2000s draw on the traditional styles and iconography of the designer’s native land—imperial dragon embroidery, Tibetan tangkas, mandarin headpieces, and silk garments. Other golden dresses featured in the exhibition include John Galliano’s 2004 gown for Dior, fashioned from tiny gold metal tiles and tassels, and Chanel’s 1996 dress embroidered with gold thread and sequins.

Branly’s vast collection of native costumes and especially wedding dresses provides insights into the long lineage of weaving and embroidery with gold thread that inspired a lot of contemporary haute couture. For example, the exhibition displays a traditional 19th-century wedding gown from Turkey, which is embroidered with gilded silver wire to create a tree pattern called bindalli (“a thousand branches”). Such robes were produced by professional ateliers and reused for different occasions. This pattern is still popular in Turkish fashion design.

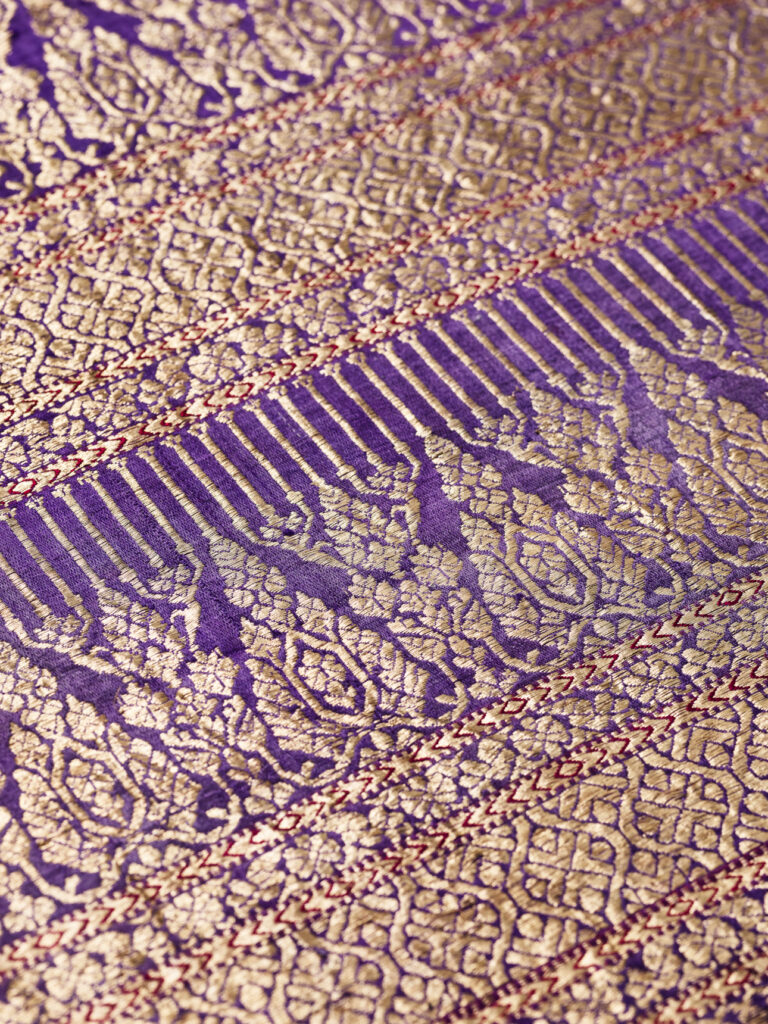

Particularly interesting is the collection of fabrics that utilized a combination of silks and various techniques of creating a gold thread—either by wrapping gold wire around silk or linen or even an animal gut base, or by weaving the wire into a strong linen or wool fabric. Branly has a large collection of Cambodian and Indonesian skirt wraps, sarongs, and Indian saris that demonstrate the centuries-old craft of gold embroidery.

The exhibition ran from February 11 through July 5, 2025 at the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris.

Couture at the Louvre

Lastly, the mother of all art museums in the world, the Louvre, has selected its Department of Decorative Arts wing as a fabulous background for dozens of masterpieces by couturiers who were inspired by France’s cultural heritage. During the Second Empire—that is, the reign of the last emperor of France, Napoleon III (1808-1873)—these rooms were used as state apartments and as a residence for the Minister of State. After the fall of the empire in 1870, the space became an official residence used by the Ministry of Finance. Since 1989, the rooms have been integrated into the Louvre’s museum space for decorative arts.

The gems of the couturiers’ collections are placed in the context of the Louvre decorative arts that inspired them.

A perfect example of an artwork from the Louvre informing the esthetics of a fashion designer is this ensemble of an embroidered blue top and an ostrich feather skirt, which comes from the last collection by Karl Lagerfeld presented for Chanel during the designer’s lifetime. It is inspired by an 18th-century lacquered chest of drawers by a designer named Mathieu Criaerd, which he delivered in 1743 to his client, Countess de Mailly at the Château de Choisy. Rococo furniture was often decorated with motifs from Chinese porcelain and woodwork, and in his lacquered chest Criaerd was aiming for an effect of blue-and-white porcelain of early Qing dynasty vases. Lagerfeld’s jacket emulates the whiteness of the lacquer in sequins and the design scrolls in blue embroidery.

Coco Chanel, known to everybody as the designer who almost single-handedly moved fashion from the Victorian gowns to the flapper style of simple, short folds of fabric, surrounded herself in her private life with the Rococo style. In her residence at 31, rue Cambon, above her fashion house, her flat was decorated with Chinese screens made from Coromandel lacquer panels produced by the great French ébenistes of the 18th century. One of the most famous was Jacques-Philippe Carel, a Parisian cabinet-maker whose furniture incorporated lacquer work imported from China or designed in a style that emulated the Qing dynasty designs.

In 1996, Karl Lagerfeld, who was a chief designer for Chanel, created an evening coat inspired by a commode by Jacques-Philippe Carel. Both the coat by Lagerfeld and Carel’s commode are now displayed at the Louvre side by side—an exquisite duo of Rococo imagery.

The exhibition Louvre Couture: Art and Fashion Statement Pieces runs from January 24 through August 24, 2025 at the Louvre in Paris.