Food for the Soul: Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art

“My world is one of crime. I steal from every artist around the world.”

~ Wayne Thiebaud

By Nina Heyn

There are curiously few cityscapes in 20th- and 21st-century art. Impressionists documented the Paris of the last decade of the 19th century, but from about the 1900s until today, artists have been more interested in painting abstractions, fantasy images in either surrealist or pop styles, or art brut that reimagines the most desolate elements of urban landscapes. It’s harder to find important paintings that portray actual city life—cars, streets, shopping malls—in other words, the urban reality of the last 100 years.

Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021), the recently deceased centenarian painter, was one who did turn his artist’s gaze onto the streets, stores, and objects around him. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco has organized at its Legion of Honor location an exhibition of Thiebaud’s work, Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art. The artist lived in Northern California and taught for decades at local universities. He became known in the 1960s for his pop-art-themed pictures of lipsticks, soda bottles, and gumball machines, but he went on to paint for another half-century, moving on to landscapes and especially portraits.

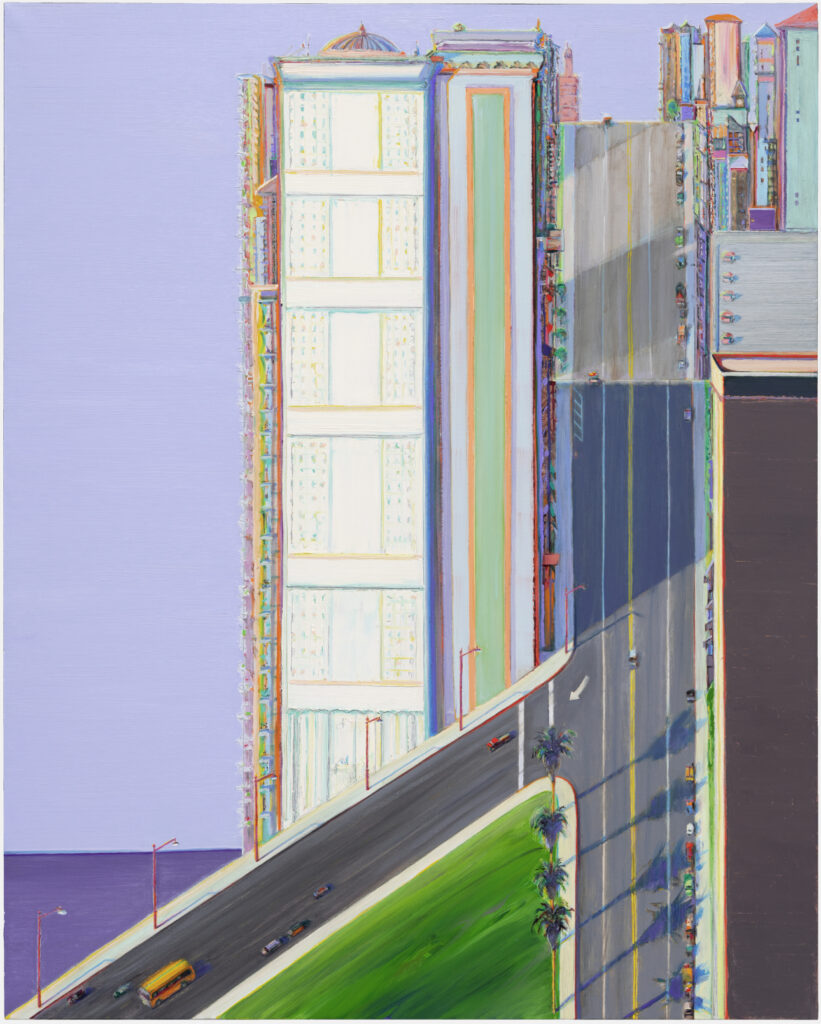

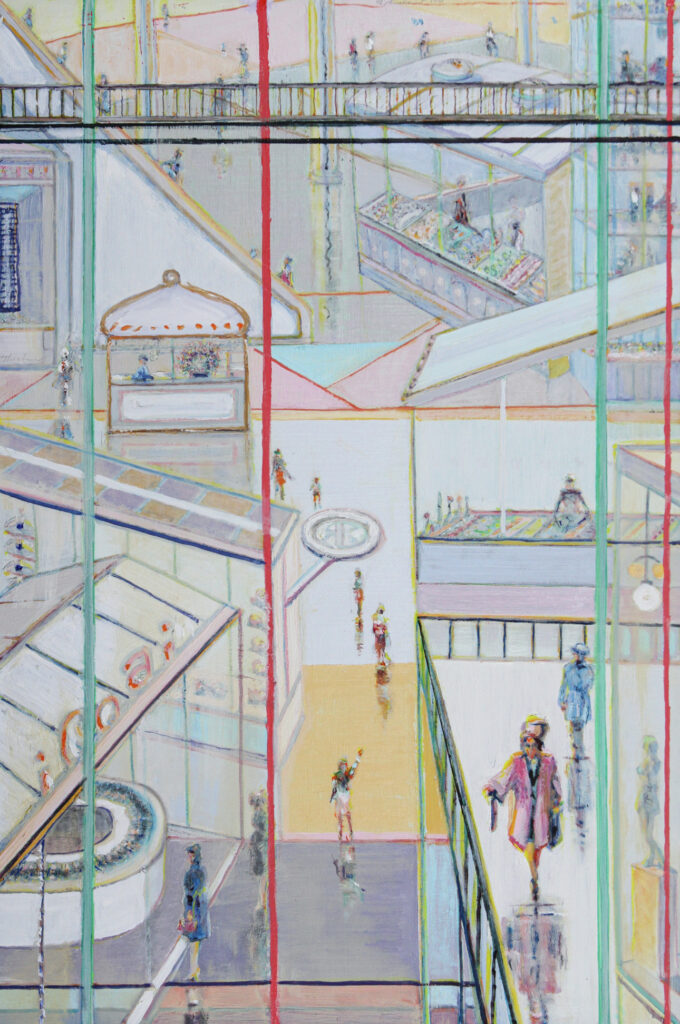

Seemingly in the majority—if not all—of his paintings, Thiebaud would reinterpret, enter into dialogue with, or transform ideas and images from other artists’ works. He often followed Picasso’s motto that “good artists copy; great artists steal” by reinterpreting art history’s iconic works, as well as paintings from his own collection or his visual discoveries. The current exhibition of dozens of Thiebaud’s paintings curates a selection of landscapes, portraits, and still-lifes in the context of artworks with which they are in visual dialogue. The one above is influenced by Mondrian’s crisscrossing divisions of canvas, whereas his other cityscapes, especially New York City 2 and Window Views below evoke both the palette and light of Richard Diebenkorn’s abstracts (which Thiebaud often referenced), as well as the art of one of his preferred artists, Pierre Bonnard, in his painting Dining Room Overlooking the Garden.

Downtown San Francisco is all about verticality: streets that undulate up and downhill, and skyscrapers that rise toward morning fog and disappear in it. Thiebaud captures that in his stunning Window Views, a picture that shows vertical bands of the U-turning road, the buildings that seem to be stacked on top of each other (he placed some landmarks of downtown San Francisco as if they were all grouped along just one street)—all these urban elements seem to be suspended in the air until you look at the person at a table beneath and realize that this is a view you could have from a window of a high-rise office. The bottom strip of this painting revises the entire experience—the view of an impossibly steep San Francisco street is now augmented by the vertical angle and size of this street in comparison to the person sitting at a table by the window. The frame of the window that we suddenly discover beneath also underscores the vertical view, like a frame within a frame.

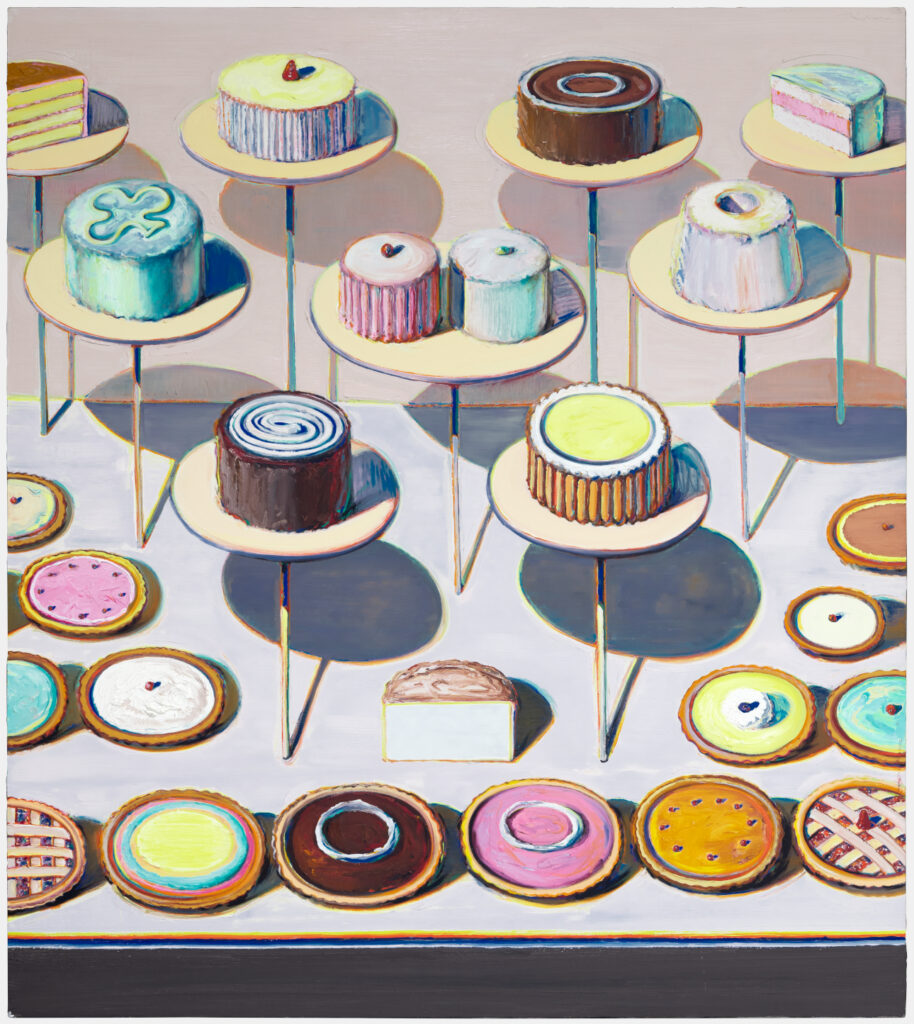

Thiebaud’s perennially popular museum favorites are those paintings of deliciously colorful cream cakes, cupcakes, and slices of cream pies. The one entitled Cakes & Pies is displayed at the exhibition with reference to artworks by Spanish artist Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560-1627), who painted in 1600 one of his bodega works called Still Life with Fruits and Vegetables. The correspondence between these artworks stems from a shared idea that these humble foodstuffs deserve to be presented like gallery collectibles—each of them in its separate space, carefully painted in juicy splendor. In the case of Cotán, these are humble artichokes and parsley roots, and in the case of Thiebaud these are cupcakes and cream tarts, but the idea is similar.

Thiebaud does not attempt hyperrealistic trompe l’oeil accuracy in his cream cakes—after all, he is not a Baroque Spanish artist but a contemporary painter making liberal use of the thick, creamy texture of acrylic paints and the psychedelic colors of synthetic food coloring. And yet the effect on the viewer can be the same—admiration of each of the objects separately, displayed like precious jewels in a case. There is also a similar mouthwatering that we associate with an especially yummy morsel. Both paintings make us think of eating tasty food.

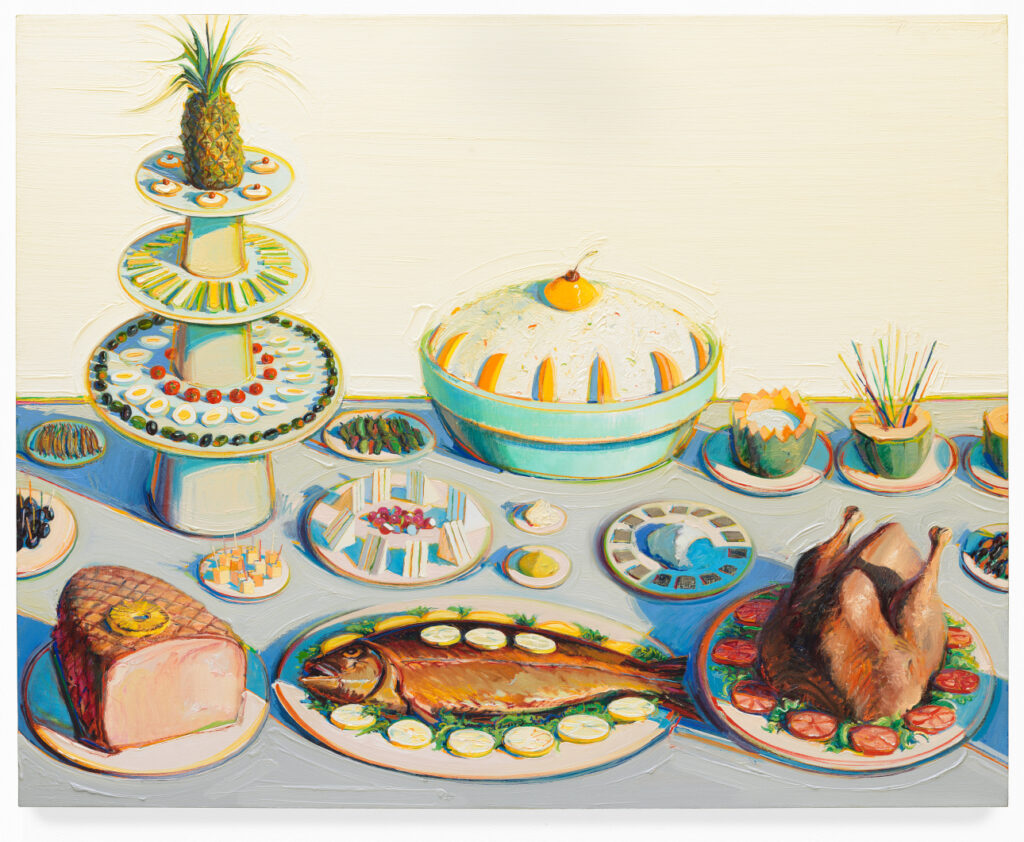

Thiebaud’s Buffet from the early 1970s is clearly inspired by Dutch Baroque still-lifes like the one below, Jacob van Hulsdonck’s Still Life with Artichokes… but the tradition of presenting food in a painterly way stretches through the centuries, as evidenced by another reference painting, that of Gustave Caillebotte’s Cakes from 1881.

Thiebaud’s fascination with arrangements, color combinations, and the shapes of cream cakes, ice cream sundaes, and chocolate desserts might have pigeon-holed him as a lesser pop artist if not for the fact that he lived and created for a long time after the pop craze of the 1960s had passed.

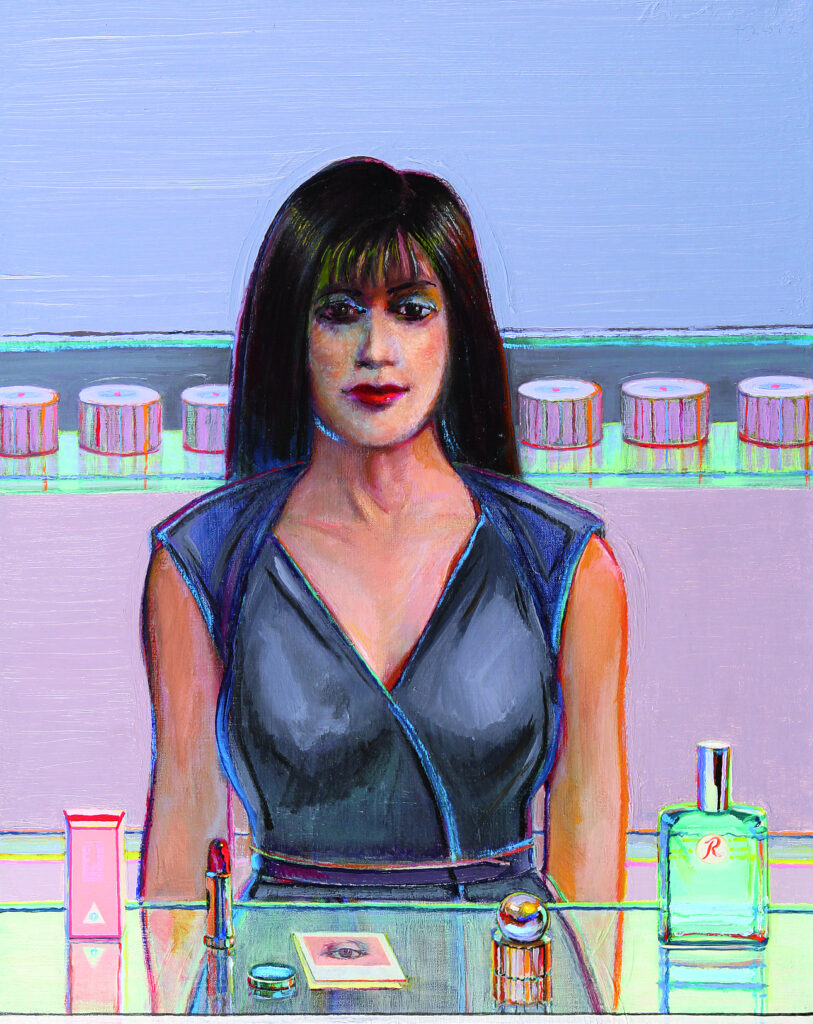

The artist seems to have had the most fun with art history when he tackled portraiture. In his picture Makeup Girl from the 1980s, he painted a seller of cosmetics at a counter you could find at any Macy’s store. Only the slightly unhealthy violet glow of the woman’s skin and the blank cobalt background hint at an idea that this is not only a portrait but perhaps a commentary on the ghoulish obsession with skin products, the commercialization of beauty, and the vacuity of the existence of this seller of products that she herself might not have been able to easily afford. And in this examination of the girl’s real life behind the professional posture of attention, Thiebaud meets the painting that inspired this theme: a very famous picture by Édouard Manet (1832-1883) called A Bar at the Folies Bergère from 1882.

Thiebaud very deliberately places his model in the same posture and with a similarly serious expression. These are both pictures of women earning their living by selling objects that are supposed to deliver pleasure (alcohol, perfume), but who themselves scarcely have entertainment on their minds.

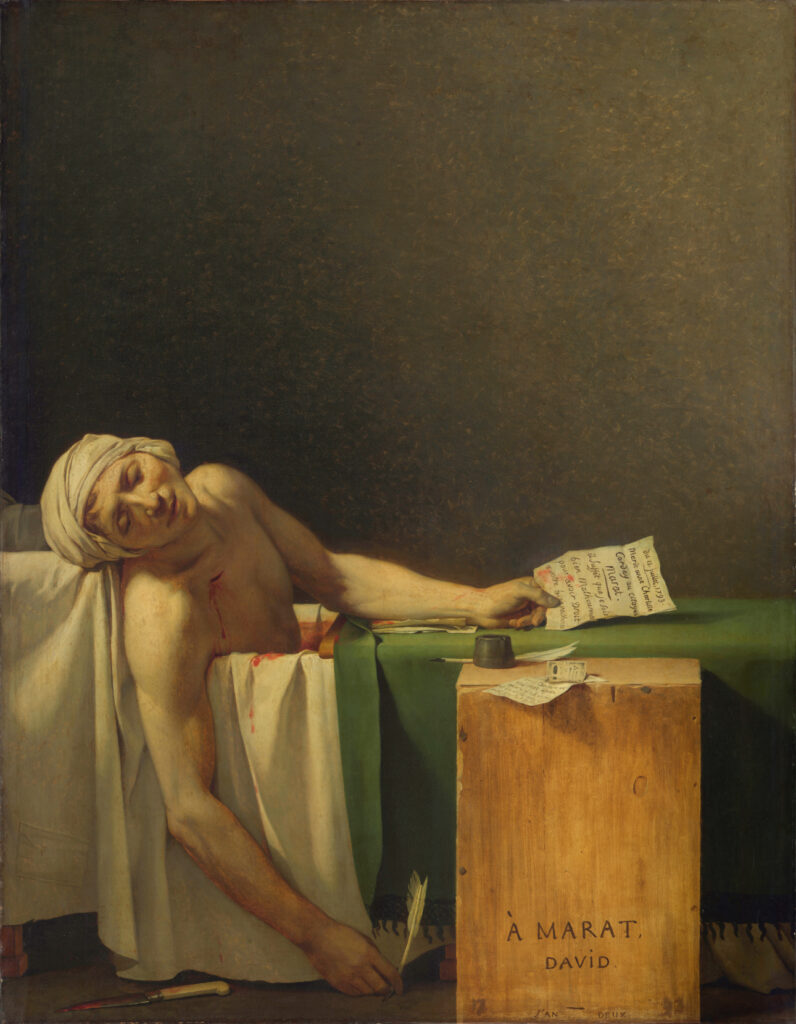

In his Woman in Tub, Thiebaud draws from Bonnard’s nude called The Bath, but he also reworks an idea of a person in a bathtub from one of the most famous paintings in art history ever—that of Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat.

Thiebaud’s figure is hardly an evocation of a pietà that David used to underscore the martyrdom of the French revolutionist assassinated in 1793. Thiebaud painted a contemporary portrait of a woman in a bathtub—perhaps someone tired after a long day—but there is no operatic emotion of martyrdom or death. The artist is interested in painting a person in the intimate, solitary activity of taking a bath, relaxed and alone; he is certainly fascinated with the blank white-on-white setting of a bathtub, but David’s famous picture is just an echo from art history’s past.

Thiebaud could take any art idea—Franz Kline’s slashes of black on white, Ellsworth Kelly’s geometrical shapes, Giorgio Morandi’s bottles—and then he would riff on these ideas the way a jazzman takes a tune and makes variations on the theme.

For anyone who delights in finding connections between modern artworks and old masters, this exhibition is a treat. Few exhibitions are curated to explain in such detail the antecedents and inspirations of modern art, but this one, thanks to Thiebaud’s self-avowed mission to reinterpret the treasury of the art world, is one big history lesson. The artist passed in 2021 at the age of 101. For the passionate art teacher that he was, this educational aspect of the show would probably make him very happy.

The exhibition runs at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco from March 22 through August 17, 2025.