Food for the Soul: Georges de La Tour Exhibition in Paris, 2025

Georges de La Tour, The Newborn Child, c. 1647-1648. Oil on canvas, 76.7 x 95.5 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes. Photo:© Musée des Beaux-Arts Rennes

By Nina Heyn

Georges de La Tour (c. 1593 -1652) was forgotten almost immediately after his death until the early 20th century, and nowadays, he is very popular. The reasons for both the forgetting and the renewed popularity are eerily similar. He painted flat surfaces and intimate settings, and his religious-themed paintings portray saints and the Holy Family as local peasants. In the context of the dramatic Baroque art of Rubens or Caravaggio and the Flemish displays of sumptuous food or busy dance scenes, La Tour’s art must have felt too simple and perhaps too inadequate for the prevailing iconography of his day. In modern times, however, his simplified brushwork and meditative mood fit well with contemporary art taste.

La Tour is often described as a “follower of Caravaggio,” but this is misleading. Not only are his compositions devoid of the violent drama of Caravaggio’s figures, but his lighting is mostly reduced to a single modest candle flame rather than theatrical side-lighting. Instead, we can just call him a tenebrist (“master of shadows”), someone who was undoubtedly influenced by the “Caravaggisti style” of such Flemish followers as Gerrit van Honthorst or Adam de Coster but perhaps not exactly Caravaggio himself, especially given that Caravaggio’s most famous artworks would have been in Rome’s churches, and it is doubtful that La Tour ever went to Italy. Nonetheless, he assimilated the elements of the Caravaggisti palette—chiaroscuro, realistic portrayals, deep and emotional spirituality—into his own stark style.

The Paris exhibition Georges de La Tour: From Shadow to Light presents examples of his earlier, less known pictures, when he was painting what he saw around him—poor villagers, blind musicians, itinerant beggars—all in a realist style close to that of the Le Nain brothers. Even then, however, instead of painting small genre vignettes of peasant life in the manner of the Dutch Baroque, he painted his peasant models on the large, vertical canvases more typical of formal portraits of aristocrats and rich burghers.

From the same year, 1620, as the Hurdy-Gurdy Player painting above, comes Saint Phillip, a picture in the naturalistic style of La Tour’s early years but already composed in the way that would become his trademark: as a “close-up” and in a pose of contemplation or religious piety rather than as portraiture of a saint casting a bold, frontal gaze. Stylistically, this painting is not yet the La Tour of his later court paintings of card players or his subsequent meditative religious art.

La Tour started life in an independent duchy of Lorraine (in northwestern France), but the 1638 destruction of his town of Lunéville, burned during the violence of the Thirty Years’ War, forced him to seek employment at the court of the powerful Cardinal Richelieu and King Louis XIII. His painting called St. Sebastian Tended by St. Irene, which did not survive to our times (we know it from copies), was selected by the king as the sole picture that the king wanted to have in his bedroom. There could have been no better endorsement of this artist’s talent, and La Tour soon started making versions of this picture as well as various religious scenes for churches and private clients.

However, even when he was painting venerated saints, La Tour created pictures bearing his own point of view, sometimes literally. Saint Peter Repentant above refers to the stalwart of the faithful in his moment of weakness, after he had denied knowing Jesus three times before the cock crowed. We view the saint from below, as if sneaking up the stairs to the attic to see Peter sitting alone at night. He is wringing his hands, full of remorse and perhaps a bit incredulous as to how easily Jesus’s prophecy came to pass. The gospel’s rooster is his only companion, and to underscore the link between the two protagonists of this story, the artist made St. Peter’s hairstyle echo the bird’s crest.

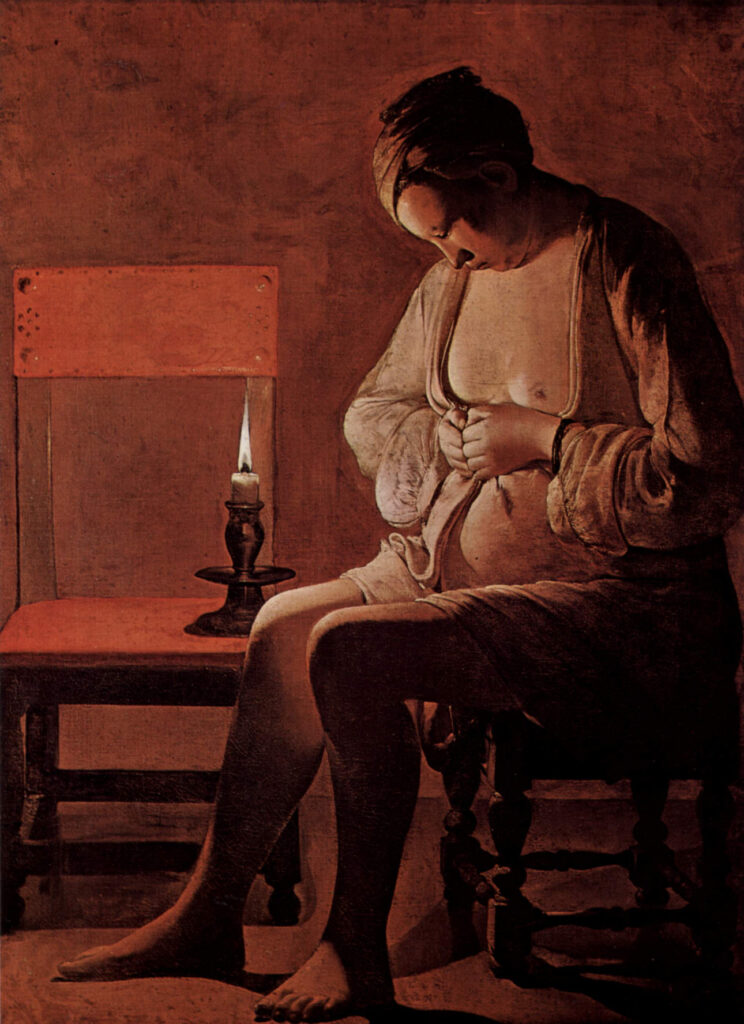

In modern times, La Tour is particularly known for his most powerful images: those candle-lit portraits of penitent saints and reformed sinners.

La Tour painted various versions of Mary Magdalene pondering the change in her life, always painting her as a woman staying up late at night, thinking deep thoughts by the light of a single candle. The version shown at the exhibition (from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC) shows a woman dressed in the most simple of night shifts, with no jewelry, and lit by a small flame that is mostly blocked from our view by the skull she is contemplating.

What a contrast with the typical portrayals of the same scene by his contemporaries, who showed Mary Magdalene as a woman covered in sumptuous silks, with the pearls she rejected dramatically strewn across the floor or a decorative snake of sin underfoot, and sometimes her head thrown back in ecstasy.

In La Tour’s later paintings, those single candle lights became his artistic hallmark, allowing him to introduce emotions in an understated way. Religious ecstasy, military violence, wailing sorrow—these types of dramatic swings of human behavior are mostly absent from his canvases. Instead, he wants to communicate things that are nearly impossible to show—an inner thought, a moment of religious contemplation, or a feeling of loneliness.

La Tour was rediscovered in 1915 by a young German historian, who recognized two paintings in a museum in Nancy as being connected to documentation about a certain Georges de La Tour from Lunéville. The historian’s academic paper on the subject launched modern research into this mysterious painter. Numerous La Tour paintings were found or reattributed to him over subsequent decades of the 20th century.

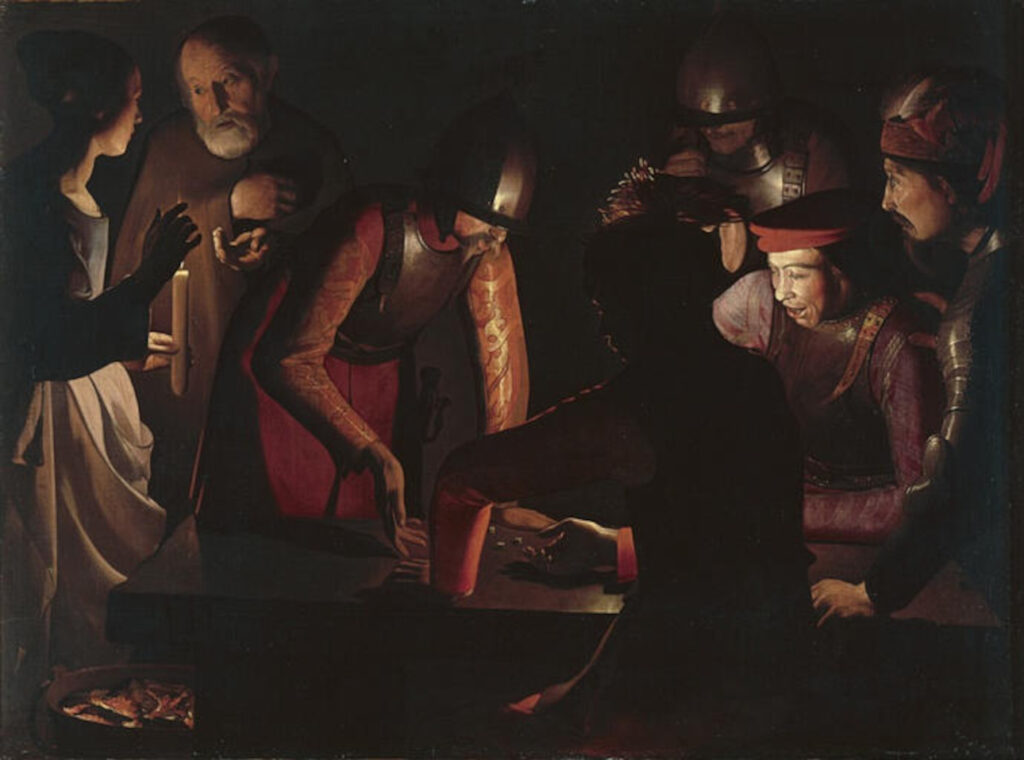

Such was the case for a tour-de-force tableau called The Dice Players. A Christie’s auctioneer who was doing an estate sale inventory discovered this painting in January 1972 in an attic in northern England. The picture was rapidly admitted into the canon of La Tour’s work, and it is now part of a local collection in Stockton-on-Tees in the UK.

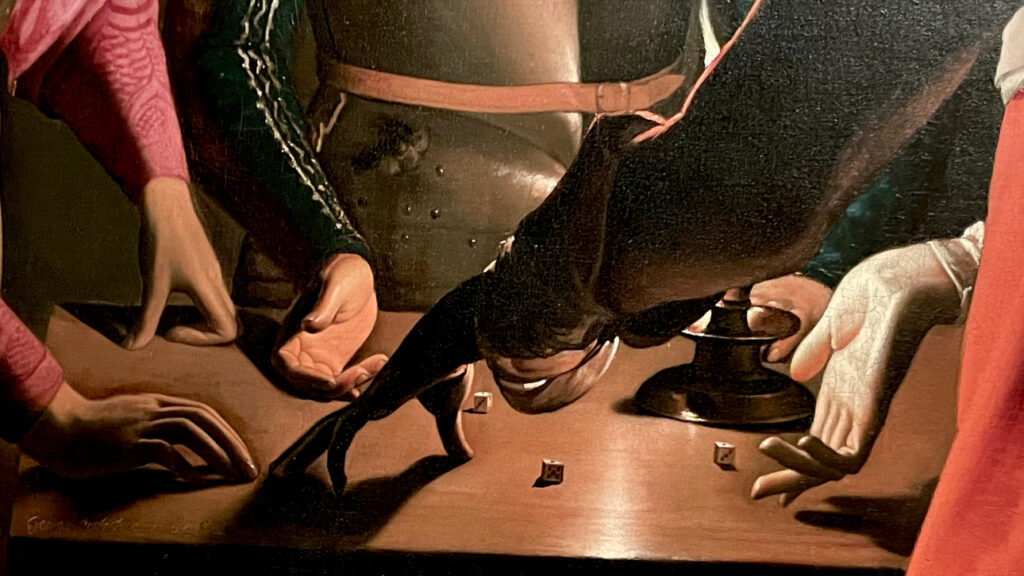

In the painting, three people are playing dice, while two on the opposite sides are just watching. One man is puffing on his pipe and looking more at the players than the throw of the dice, but the person on the right is focused solely on the movement of the game cubes. This is a painting and not a movie with sound, so we can only infer action and words from the looks and gestures. La Tour excels at conveying the drama this way: it is the regard of the man on the right, avidly concentrated on the hands of the players, that draws our attention to the positions and shapes of the hands. Here is a close-up of just the hands—this is where all the tension and action are unveiled.

Georges de La Tour. Detail from The Dice Players, c. 1640-1652. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 130.5 cm. Preston Park Museum, Stockton-on-Tees, UK. Photo: © Nina Heyn, 2025

Some hands are full of tension, some are in movement, and some are resting—all of this is lit by one candle with its flame mostly blocked by an arm, an old trick of La Tour to provide some light but not too much. There is an air of mystery and maybe even conspiracy, all of it so different from the hysterical battle scenes by Baroque contemporaries of La Tour.

It is estimated that throughout his lifetime the artist painted from 300 to 500 works, but only about 40 have survived. The exhibition brings together about 30 of them—a major achievement in the art world. Georges de La Tour: From Shadow to Light runs from September 11, 2025, through January 25, 2026, at the Museum Jacquemart-André in Paris.