Destinations: Rubens in Antwerp

“I’m the busiest man in the world, and the most under pressure!“

~ Peter Paul Rubens in a letter to Palamède Fabri de Valavez, January 1625

By Nina Heyn

The image of a struggling, unappreciated artist doesn’t apply to Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). As a child, he was accepted as a page at a noble house to learn social graces, at 14 he started an apprenticeship with major painters of his time, and by the time he was 21—soon after moving to Italy as a court painter of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga—he was already a member of the painters’ guild.

By 1609, Rubens was in the prime of his life. Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, and his wife Isabella Clara Eugenia appointed Rubens as a painter to their court; the court was in Brussels, but Rubens was allowed to settle in Antwerp, where he had grown up. From then on, Rubens would be very busy completing one major court or church commission after another, supervising his large, busy workshop, and traveling all over Europe on diplomatic missions. He was admired by royal patrons and fellow painters alike—successful as a courtier and diplomat, accomplished as a businessman, and respected as a giant of art history. As an artist, his art linked the Renaissance to the Baroque, and he excelled at anything he touched (original compositions, huge historic tableaux, important portraits) while also introducing new techniques and ideas.

In the middle of Antwerp, there is an imposing house and garden established by Rubens as his primary residence and which he designed to emulate Italian Renaissance palazzos and gardens. The result, one of the grandest residences in Antwerp, is still a major landmark today. On the outside, the house is built in the traditional Flemish brick style, but the inside areas reveal an enchanting courtyard with an imposing stone façade in the Italian style.

A portico separates this courtyard from a garden with statuary, fountains, flowerbeds, and whimsical columns. This Baroque estate is now a Rubens museum that has in its collection not only his works but also artifacts and paintings by other artists that he collected.

The interior is under renovation until 2027, but the garden is open, and there is an interactive educational area where you can experience the life and art of Rubens and his contemporaries. Various digital displays allow visitors to imitate poses in paintings shown on screens. You can also pretend you are commissioning a Rubens artwork and, depending on the criteria chosen, you will end up with an image of something he or his workshop produced (for example, do you want wild animals? a court scene? a family portrait?). You can even test your connoisseurship of styles by deciding if a picture was painted by Rubens or some other famous artist.

Visiting Rubens’s house is good start to learn about this Baroque titan of productivity and talent, but afterwards, you have to wander around the city to have a first-hand experience of Rubens’s art. Like with Caravaggio in Rome, many Rubens paintings are still where he painted them—in some of the most imposing churches throughout the city.

While artists in the neighboring Protestant Dutch Republic had to switch to painting genre scenes when the churches were emptied of any iconography, Catholic Antwerp was overflowing with commissions for church altar and chapel decorations. Sculptors, metalworkers, and above all painters in 17th-century Antwerp were most sought after. The one most in demand was Rubens, whose workshop could barely keep up with the flow of orders for altarpieces, tapestry cartoons, portraits, and religious triptychs.

Antwerp is the location of the largest Gothic church in Belgium, the Cathedral of Our Lady, a 400 ft (121 m) stone and brick structure which started construction in 1352 but did not finish until 169 years later, in 1521. There is a large statue of Rubens in the Green Square on one side of the cathedral—a perfect location to commemorate the artist whose monumental panels are the cathedral’s biggest treasures.

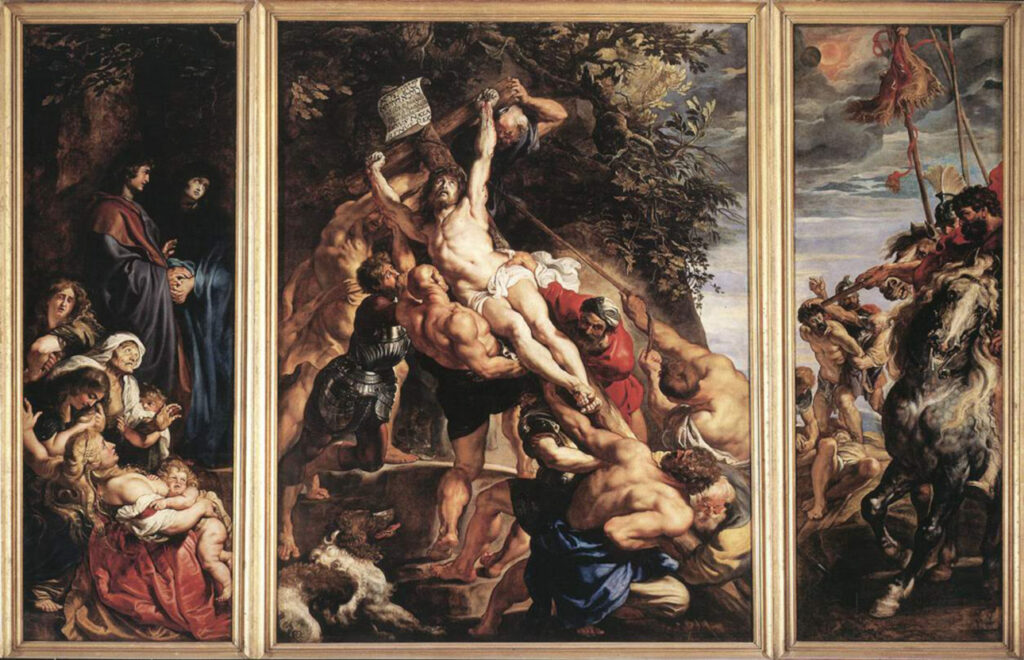

The cathedral contains four Rubens altarpieces: The Raising of the Cross, The Descent from the Cross, The Resurrection of Christ, and the central altarpiece: The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin.

The Christ martyrdom scenes were all painted for specific altars in Antwerp, designed and partially painted by Rubens and worked on by his assistants. The Assumption panel depicts a less tragic subject, and its spirituality is rendered with more of an Italianate, flourishing style, typical of both Rubens and the Baroque. The ascending Mary is gracefully rising in the flutter of her robes and flowing long tresses, surrounded by a garland of sweet putti; below, the crowd of amazed people includes three women, of which the central figure has the features of Rubens’s first wife Isabella Brandt (who died in 1626 while he was working on this piece).

The other church in Antwerp that boasts of a major Rubens presence is St. Paul’s Church, a structure that has undergone, over 500 years, countless changes: demolishing and rebuilding, fires, looting, bombardment, a flood, and a public sale after the Dominican Order was abolished in 1796. One of the Rubens paintings was looted by the Napoleonic army, then given to a church in Lyon and not returned to this day. The Rubens work that does remain in this church is his Adoration of the Shepherds. Painted in 1609—the year Rubens returned to Antwerp after eight years spent in Italy, where he absorbed art influences from Michelangelo to Caravaggio—this work is very much indebted to those artists, with Italianate chiaroscuro and an arrangement of figures in flowing lines.

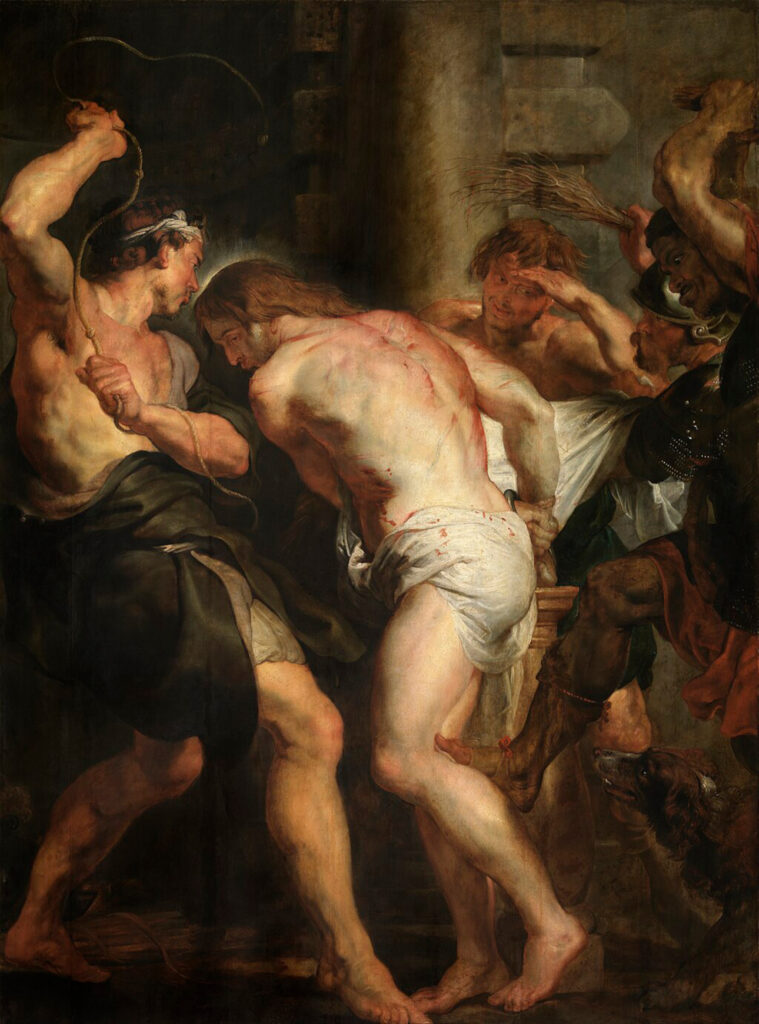

Painted 10 years later, when Rubens’s artistic maturity had reached its apogee, Flagellation of Christ is a life-size picture of two figures in a dramatic dance of suffering—the central figure of Christ being tortured and his persecutor raising a whip, with another man raising a stick and placing his foot on the leg of his victim. There are no hovering angels here or virgins in flowing garments, nothing that would make this scene of suffering less real.

The church is undergoing a major renovation and, for a time at least, you can see this painting from up close.

At present, it is positioned at eye level, and as an added bonus, you can compare it with another canvas placed facing it: Jesus Bearing the Cross by Rubens’s most gifted student, Anthony van Dyck, who painted this theatrical scene of Jesus Bearing the Cross when he was 18 years old. While his youthful brushwork lacks the precision of his master, he makes up for it with the energy and the drama of the scene.

The main art museum in Antwerp is called the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA in the Flemish acronym), and this is where some of the best-known Rubens works reside. Some of them are religious, like the triptych of The Doubting of St. Thomas as well as The Lance or Christ on the Cross. The most spectacular among them is his Adoration of the Magi, a painting that has a permanent place in the history of art.

It is one of the four well-known Rubens compositions on the theme (the other three are in museums in Madrid, Lyon, and in King’s Chapel in Cambridge), and it is my favorite. Much has been written about this painting’s composition of vertical columns and Rubens’s application of the rapid ochre-paint brushstrokes for some background figures—a technique that traditionally would have been reserved for oil sketches. It may have something to do with the fact that he painted this monumental (447 x 336 cm; 14,6 x 11 ft) picture in barely two weeks.

Mary, who is proudly presenting her baby to the kneeling king, is actually on the side of this composition. The center is taken up by King Balthasar, whose intense look, imposing figure, and bright green costume are counterbalanced by the red cloak of the third king who is staring at us, the audience. These three kings are the source of the biggest drama here. I also love the exotic accent of not one but two cheerful camels in the back. A staple of most other nativity scenes, the donkey is nowhere to be found, and the traditional ox is positioned low at the right corner, almost like a faithful dog at Mary’s feet.

The versatile, talented, well-educated, and well-traveled artist-diplomat had extensive connections to the Flemish elite as well as to aristocratic patrons in Italy, France, and England. These titled collectors would often demand exotic hunting scenes, mythological or biblical stories, battle scenes, or even erotica dressed as allegories. Rubens would comply, creating such paintings as Venus Frigida and The Prodigal Son, which are in the KMSKA collection.

Venus Frigida shows the goddess of love accompanied by her son Amor, both of them shivering with cold. A satyr in the background is trying to revive her with a horn of plenty with wheat and fruit. This is an illustration of a quote from Terence, the Roman antiquity comedy writer who said, “without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus freezes” meaning that “without food and wine, love withers.” The landscape on this panel was painted by another artist, and the picture was enlarged after Rubens’s death, possibly to better suit some decorative space.

The Prodigal Son is an interpretation of the popular biblical parable of the return home of a wastrel son, but for Rubens, this was more an opportunity to create a country life scene. While the titular young man kneels to the side, begging to be taken back into the fold, most of the space in the picture is taken by a very detailed view of the well-appointed stable and cow barn, with a view of the courtyard all the way to the fields beyond, lit by the idyllic lavender-and-pink skies of the setting sun. The composition is framed with wide horizontal and vertical lines of the barn’s beams, and there are several sources of light: a candle in the background, bright light on the glistening skin of the son, and the hazy light of the evening over the fields.

Rubens is famous for his voluptuous nudes (“Rubenesque women”), his dramatic religious tableaux, and his portraits of important personages of his time. However, had he lived much later, when artists were less dependent on church commissions and patron-directed themes, he could have been an amazing landscape artist. There are many canvases that he created later in life that attest to his prowess and his fondness for landscape pictures, a genre that was barely nascent during his lifetime. The Prodigal Son is a painting that attests to Rubens’s lyrical and compositional mastery. The artist himself must have felt particularly attached to this painting because it never left his household during his lifetime.