Food for the Soul: The Year of the Fire Horse

By Nina Heyn

Horse paintings, sculptures, paper cuttings, and prints have always been extremely popular in Chinese decorative art, and especially ubiquitous in a Year of the Horse. In Chinese astrology, each Year of the Horse denotes persistence, hard work, leadership, openness, and vitality. This year, the intertwining of the horse sign with the elemental force of fire means that when the Chinese New Year starts on February 17, 2026, it will be, for the first time since 1966, the Year of the Fire Horse. This special combination occurs once in 60 years, and it is associated with breakthroughs (as in “horse leaps”), innovations, and sweeping changes. Sometimes, rapid changes might not be so positive; the last time the Fire Horse occurred, it brought the start of the Cultural Revolution in China. Let’s hope that this time the Fire Horse will bring renewed energy and fiery creativity rather than tumultuous times.

The Chinese love of the horse started a very long time ago. In 102 BC, Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC), one of the most powerful emperors in Chinese history, sent a military expedition to a land called Dayuan in the Ferghana Valley in Central Asia. It was inhabited by descendants of the Greek, Bactrian, and Parthian civilizations. An army of 60,000 of the emperor’s men besieged the capital, forcing surrender. The inhabitants negotiated peace using as a bargaining chip their prized horses, which they threatened to slaughter if their city was not spared. The peace terms yielded to the Chinese army a treasure of 3,000 horses, including about 30 “heavenly horses” and a subsequent tribute of two such horses a year. The horses were sent to the capital, together with seeds of alfalfa (called “lucerne” in Europe)—a plant necessary to feed horses a better diet than the short grasses of the Asian steppes.

The Ferghana horses were dubbed “heavenly” due to their superior looks and strength as compared to the usual small mounts of the nomadic tribes. Their strong legs and large powerful bodies have been immortalized in countless bronze and ceramic sculptures and paintings of the Han and Tang dynasties. One of the most famous of these sculptures, called Galloping Horse, depicts such a stallion running at a full gallop. His ability to move with superior speed is underscored by the swallow that he is crushing under his hoof, thereby proving he is faster than even a wheeling bird.

The Ferghana horses provided the Chinese cavalry of subsequent dynasties with powerful warhorses, immortalized in tomb pottery in many burial mounds throughout the empire. These powerful, large, fast animals were a game changer in the military conquests and wars waged by emperors of the Han, Tang, and Song dynasties. It is no wonder that in Chinese culture, mythology, and literature, the horse symbolizes strength and peace. “The strength of dragons and horses” (in Mandarin Chinese: long ma jin shen 龙马精神) is a popular phrase for New Year’s wishes calligraphed on banners to decorate the house.

Western iconography owes much to antiquity’s portrayals of rulers, conquerors, gods, or heroes posed in triumphant stride on a massive horse. One of the most impressive and much-copied equestrian statues is that of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE). Nowadays, this bronze figure from the second century is kept inside Rome’s Capitoline Museums, but it spent previous centuries decorating the city’s plazas. In the Middle Ages or Renaissance, such a huge bronze statue of a “pagan” ruler or god would end up either destroyed by papal order or melted down for cannons. The monument of Marcus Aurelius is the sole one of this size to have survived, thanks to the erroneous belief that it was a statue of Constantine, the first Christian emperor, rather than the “pagan” emperor of an earlier era.

For almost a millennium, antiquity’s tradition of seating a ruler on an impressive warhorse disappeared, only to be revived in about 1447 when Donatello created his Equestrian Statue of Gattamelata in Padova. The artist had the equine monument of Marcus Aurelius as an example and source of inspiration, but, working almost 1300 years after the Roman bronze sculptor, Donatello had to resolve many technical challenges—including how to support the 11 x 12 ft (3.4 x 3.9 m) mass of metal on thin horse legs, out of which one is precariously balanced on a sphere. The statue was a success and firmly planted the idea of an equestrian portrait of a ruler in Western art from the Renaissance onward. Important princes and war generals of the era began to be portrayed riding a horse in a battle, on horseback in a gallop, and in elegant display poses suitable for stone and bronze statues, frescoes, and oil paintings.

Leonardo da Vinci attempted the most ambitious bronze statue of his time when he received a commission from his patron Ludovico Sforza in 1492. The artist created designs, produced a clay model, and assembled 70 tons of bronze material, but then Sforza’s military plans interrupted the project and redirected the bronze toward the production of cannons. The statue that was intended as the biggest horse in the world (26 ft; 8 m tall) was never built, and the clay model was destroyed. At the turn of this millennium, the Japanese-American artist Nina Akamu was commissioned to recreate the statue, which is now located in Milan, the city of da Vinci’s long-term residence. Other modern versions of this statue and other interpretations of Leonardo’s vision are located in the U.S. and Italy.

One of the most ingenious uses of the horse as a prop to raise the status of a king was devised around 1635 practically simultaneously by Anthony van Dyck in England and Diego Velázquez in Spain.

Van Dyck literally needed to raise the diminutive King Charles I (he measured 5 ft 4 in, 162 cm) to a height suitable for a “King of Great Britain” (this is how he is identified in the painting). The canvas itself is enormous (12 x 9 ft 7 in; 367 x 291.1 cm), and it increases the feeling of grandeur that must have been the aim of both the artist and the sitter. Van Dyck painted other equestrian portraits of his master, out of which the most famous is Charles I with M. St. Antoine, but they are less dynamic. This picture takes full advantage of the horse as an attribute of a royal and a hero worthy of its models in antiquity.

Velázquez had a similar problem with his patron, the Spanish King Philip IV. How to show a ruler of half of the world, when nature had gifted him with an elongated Habsburg jaw, short legs, and a slight build? You put him on a horse that is raising its front legs in the graceful and difficult courbette pose, urged up almost imperceptibly by the king’s golden spurs. This is a portrait of a ruler in action, a skilled rider, and even a military leader, as indicated by the half armor.

By the 17th century, attitudes toward leisure horses (not the poor beasts used for farm work or transportation) had changed as well, at least in art. Artists started to show horses as individuals, not just as edifying props. Animal painters like the Dutchman Paulus Potter (1625-1654) would show horses in all their grace but have them standing alone, without the distraction of a nobleman owner or groom holding the reins.

Thoroughbred horses did not appear in Europe until the next century, and when they did, their portraits soon found their way onto canvases. The unequaled master of horse painting, the self-taught Englishman George Stubbs (1724-1809), devoted his life to the equestrian genre as well as to painting exotic animals.

In 1762 when Stubbs painted Whistlejacket, the importance of the horse in British society was at its peak. Not only did horses provide the power to plow fields and operate mines or freight delivery, they were also the sole means to transport people everywhere. At the pinnacle of the horse’s usefulness was horse racing—the noble sport of the aristocracy and the passion of millions who would bet or at least watch the races, whether the big ones like Ascot or simple local events every Sunday. It is that use of the horse—as a racehorse carefully bred, schooled, raced, exhibited, and put to stud or traded—that Stubbs immortalized in his huge (115 x 97 in; 292 x 246.4 cm) painting.

Stubb’s clients, English aristocrats with large estates and stables full of horses more valued than houses, would commission him to portray the best specimens of the breeding aimed at producing racecourse champions or superior hunters. Whistlejacket, one of the most celebrated paintings in the National Gallery in London, is Stubb’s masterpiece of equestrian portraiture. There is nothing but the horse in this picture, not even an artistic crutch of a tree, a background landscape, or a road to stand on. This painting communicates the essence of a thoroughbred horse—the sheer power of the racing muscles, the unrivaled jumping ability, and the beauty of a coat groomed to perfection. This is not far from the artistic intention of a Chinese bronze master—it’s an artist’s sheer admiration of the equine shape for itself, with no external elements needed.

By the 19th century, horses in art were no longer just attributes of rulers, even though historic canvases—so beloved by neoclassic Victorian-era painters and critics—were still being painted by the thousands, full of half-naked gods, heroes, and victims, writhing on and beneath foaming horses with flowing manes.

Edgar Degas drew horses from his student days on. In his sketchbooks from the 1850s, when he was barely 20 years old, there are drawings of horses racing and his copies of famous horses in art—such as the Parthenon frieze or the del Castagno fresco at the Florence Duomo—which he did while traveling extensively throughout Italy.

Later, during his stays at the Chateau Ménil-Hubert, invited by his collector friend Henri Valpinçon, Degas would have the opportunity to observe carriage horses as well as racing champions at a nearby course. In the France of the mid-1800s, horseracing became a new fashion imported from England, and Degas’s pastels and oils of racing tracks, full of jockeys in colorful silks mounted on the elongated shapes of thoroughbreds, pleased his clients enormously. One of them, Count Isaac de Camondo, purchased a painting called The Parade or Racehorses in Front of the Stands, which he bequeathed to the French state in 1911. Even though this picture was painted in a studio, it feels as if Degas captured it on the spot, with the horse on the right walking across, out of the frame. Spectators and assembling jockeys on their mounts are all lit with the sharp morning light.

The Symbolist painting above, Ectasy, was painted at the end of the 19th century by a young Polish artist, Władysław Podkowiński. Here, the horse serves to express the wild, “animal” instincts experienced by the naked woman, and the horse itself is a creature possessed with uncontrollable vigor or even madness. Podkowiński developed the idea for this painting while living in the liberal, artistic city of Paris, but by the time he got around to painting the canvas, he had returned to the much more conservative Warsaw of 1894. To imply that this naked woman was in the throes of a sexual swoon was too much for the Victorian-era society. When he displayed the painting at an exhibition, the resulting public outrage and press attacks were relentless. It did not help that Podkowiński was secretly in love with a married woman who had rejected him and who was most likely the one he painted in Ectasy; consequently, the woman’s family erupted in public fury as well. The frustrated artist went one day to the exhibition, climbed a ladder, and slashed the picture with a dozen strokes of a knife, aiming mostly at the figure of his platonic love. A few months later, the artist died of tuberculosis, hastening his end with fasting and depression. The painting was later restored and exhibited anew, with the proceeds from the exhibition donated to the artist’s old mother. Today, it is one of the best-known and most often reproduced paintings at the National Museum in Kraków.

Alfred Munnings (1878-1959) is celebrated in England as one of the most sought-after equestrian painters (in 2007, for example, one of his paintings reached over $7M at Christie’s). He was also one of the last artists active in the 20th century who favored a traditional, realistic style over any of the “avant-garde” works of Cézanne or Picasso, whose art Munnings openly despised. His preference for both realism and the subject of horses secured him countless commissions from horse owners—a following that made him famous and wealthy. During WWI, he served as a war artist within the Canadian Cavalry Brigade and painted numerous canvases of warhorses and their cavalry riders. The First World War was the last time that horses were used extensively in war, since by the beginning of the second, animals were replaced by tanks, airplanes, and all-terrain vehicles.

In 1918, Munnings painted a portrait of a prince who was a member of both Brazilian and French imperial families. Captain Prince Antônio Gastão of Orléans-Braganza volunteered to serve in the Canadian cavalry, and this portrait captures him and his equally aristocratic-looking mount, both shown rigidly straight, both regal in an afternoon sun. Contemporaries described how Munnings kept his human and equine models posing for hours, trying to capture the correct shade of bluish shadows on the horse’s rump, brushed to perfection.

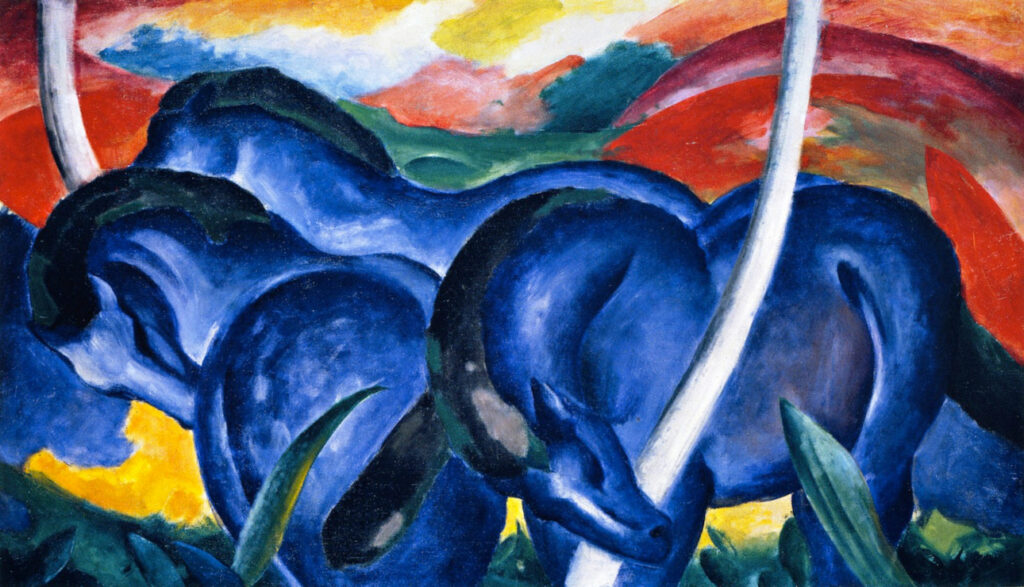

Munnings’ traditional tastes notwithstanding, Realism as an art style could not last in the face of the war atrocities, new technologies and speeds (from cars to airplanes), and the need of the new generations to find a different way to describe the world around them. Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) was one of the many new trends, schools, styles, and artistic circles that sprouted in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. The German painter Franz Marc (1880-1916), together with August Macke and Wassily Kandinsky, formed a group that eschewed realism, both of drawing and color. Marc is best-known for his paintings of the blue horses that gave the name to the movement. His 1911 canvas, Large Blue Horses, is one the best examples of Marc’s vision of horses as mysterious, sinuous shapes, enhanced by their other-worldly ultramarine blue. For Marc, the color blue signified both spirituality and masculinity—perhaps the two features he prized the most. Neither feature was able to save him, however, from a tragic fate; he was drafted at the beginning of the war and killed at Verdun in 1916. Later, the Nazi German government declared his art degenerate—the bluishness of his horses was not realistic enough for them. By 2025, however, Marc’s painting called The Foxes, which was recovered from a WWII loss by a Jewish family, sold for $57M at Christie’s.

So, in art, the image of a horse has waxed and waned together with the stature of the animal itself in society. Red ochre cave paintings from the dawn of humanity were created but then forgotten, along with the caves themselves. In ancient China, the horse was elevated to the pantheon of Zodiac animals and portrayed in the prized sculptures of many dynasties, but in modern times, horses are mainly a cultural icon of decorative art. Western art used the horse as a dramatic attribute of power, only to have modern artists deconstruct horses into essential oval shapes or symbols of speed and strength. And yet, Marc’s blue horses are not so far from the cave paintings of 20,000 years ago—both were perceived with a human eye and painted by an artist in awe of the grace and vigor of the horse.

In the Chinese calendar, the Year of the Fire Horse takes place between February 17, 2026 and February 5, 2027.