Food for the Soul: “Impressionists 1874” – How It All Began

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

No matter how much or how little we know about fine art, we can all spot the difference between paintings by old masters and the art that was launched by post-Classical artists—Impressionists, Modernists, and representatives of all subsequent movements, from Surrealism to Abstractionism.

There are various reasons for this difference. In the world before the Enlightenment, the majority of people believed that the world created by God was perfect in every aspect and to paint was to get as close as possible to that perfection. The Renaissance humanists sought perfection for perfection’s sake—the more naturalistic the representation, the better was the painting. The belief in a “Great Chain of Being” (the medieval concept of the God-ordained hierarchy of creatures, from angels to worms) contributed to the expectation that all things painted—people, minerals, or plants—should be rendered with naturalism. Artists like Cézanne and Matisse were attacked viciously for years by art critics who were incensed that a human face would be green or a table crooked, with apples ready to slide off.

The great and liberating merit of Impressionism and all the “-isms” that came after was the realization that paintings and sculptures do not have to be naturalistic copies of what we see in order to be important for our minds and souls. In fact, artists pointed out much earlier than scientists that what we think we see is only an illusion. The science of optics finally caught up with art when it declared that the brain is the place where we assemble visual cues, but that they just provide multiple, fragmentary images. Cézanne, with his various points of view in one picture, or Seurat with his pointillism, came to this conclusion when painting their pictures at the end of the 19th century.

Sometimes it is good to go back and examine where it all began. A commemorative exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism,” examines exactly that—the beginning of everything we consider as “modern art.”

First, a bit of history. Between 1667 and the early 20th century, the art market in France was dominated by the Salon—an annual exhibition of new artworks. If an artist managed to place an artwork at the annual Salon show, the Salon provided access to sales, critical acclaim, and professional recognition. Having a picture rejected by the Salon meant the opposite—few chances to be successful, either financially or among the critics. Pictures that were accepted by the Salon were usually realistic in style, conservative in subject (historical, religious, or moralistic tales fared the best), and eye-pleasing for the general public (flowers, children, portraits). Innovations were usually turned down. The 1874 edition of the Salon was as harsh as ever, accepting fewer than half of the 5,434 submissions.

The time was ripe for an alternative show. Artists and a few patrons set up a cooperative that had the goal of showcasing new works—without prizes or a jury—with the aim of reaching the public directly. The rogue exhibition of works of 31 artists that took place in April 1874 in Paris has gone down in art history as launching the movement we today know as Impressionism, and according to the oft-told tale, showcasing young artists who were rejected by the official Salon, but as often happens, this description is only part of the story. As the exhibition at d’Orsay demonstrates, this first, modest dissent from Victorian realism featured quite a lot of “traditional art.” To quote the exhibition’s curators, “In 1874, the dividing line between the old order and the avant-garde remained blurry.”

Out of the 31 artists who participated in the dissenting show, 12 showed at both the Salon and the new show, and apart from a group of pictures in the new style (painted by such newcomers as Monet, Sisley, Morisot, and Renoir), many of the paintings were done by “mainstream” realist artists whose participation had been invited to dampen anticipated criticism. Édouard Manet and his young protégée Eva Gonzales were among those who exhibited at both venues. The Railway, Manet’s powerful image of the new Paris life, was accepted at the Salon, but it could have fit in equally well among the early Impressionist works.

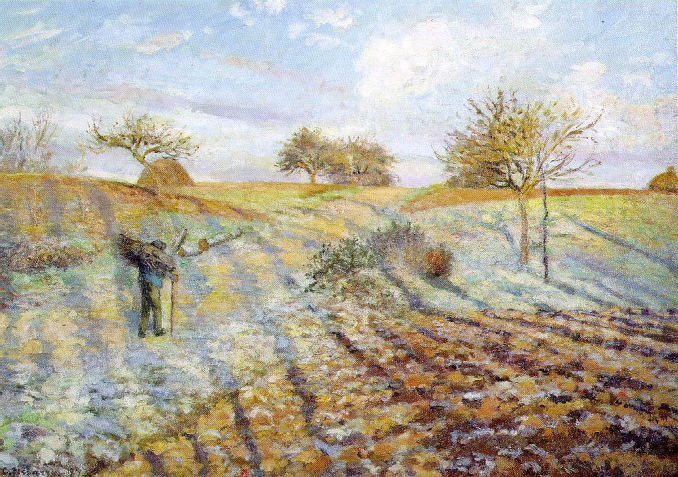

The critics predictably latched onto the most avant-garde paintings, not sparing their castigatory words. Louis Leroy, the same man whose vitriolic pen and weak understanding of art prompted him to deride the new style as “impressionism” (thus creating the name for the entire art movement) slighted Pissarro’s Hoarfrost by writing: “[A]re these furrows frost? … These are but palette scratches … on a dirty canvas.” The artist had a different opinion of his work, pricing it at 2,500 francs, one of the most expensive pieces in the exhibition. However, the picture did not sell.

In fact, out of 165 paintings listed in the catalog, only four of them sold, and surprisingly, one of them was done by an artist systematically rejected by the Salon and for the next two decades regularly ridiculed by the press: Paul Cézanne. His House of the Hanged Man sold for 200 francs. The other three artists who sold one picture each were Alfred Sisley, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Nonetheless, the new generation of artists was launched, even if the show ended up in the red: the exhibition netted 2,359 francs, which did not cover the 9,272-franc cost of mounting it.

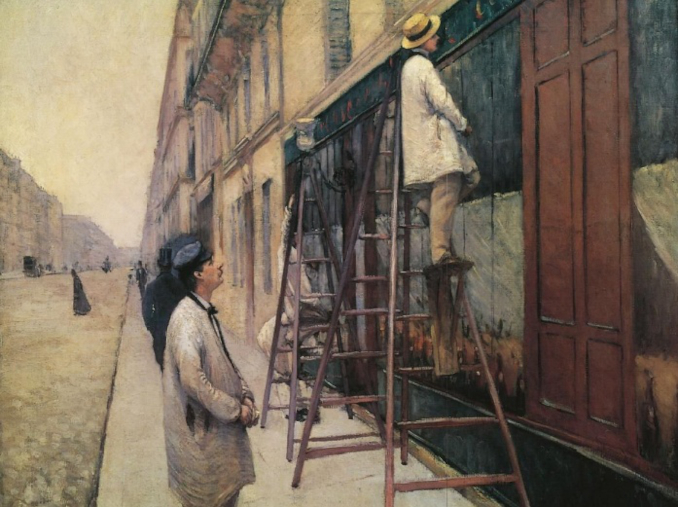

D’Orsay’s exhibition has a room devoted to the third show that took place in 1877. By that year, the new artists had come to firmly identify themselves as “Impressionists,” and the show’s 18 participants—including Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Degas, Sisley, Pissarro, and Cézanne—had matured in their style and their awareness of being in the forefront of pioneering directions in art. They had also found a new friend and patron, Gustave Caillebotte, a great painter in his own right who was blessed with family money and a spirit of generosity. Caillebotte organized and funded the 1877 show. One of the pictures exhibited there was Caillebotte’s daring composition called House Painters, which draws the eye to crisscrossing vertical lines of the road, buildings, and ladders.

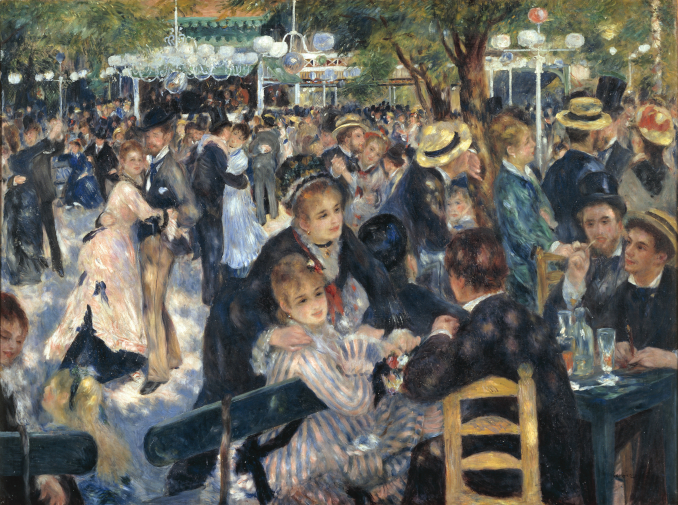

Several examples of the Impressionists’ new maturity, the complexity of their imagery, and their enormous artistic abilities—as displayed at the 1877 exhibition—are presented at the current show at d’Orsay. The most famous is Renoir’s tour-de-force group scene entitled Bal du Moulin de la Galette. It looks like a “slice-of-life” picture of young Parisians twirling on the dance floor of an open-air venue, but in reality, Renoir carefully planned this composition, including spending time at a rented place to observe the dancers and having some of his friends pose for the picture. Caillebotte, a friend and supporter of Renoir, purchased this painting and eventually bequeathed it to the French state.

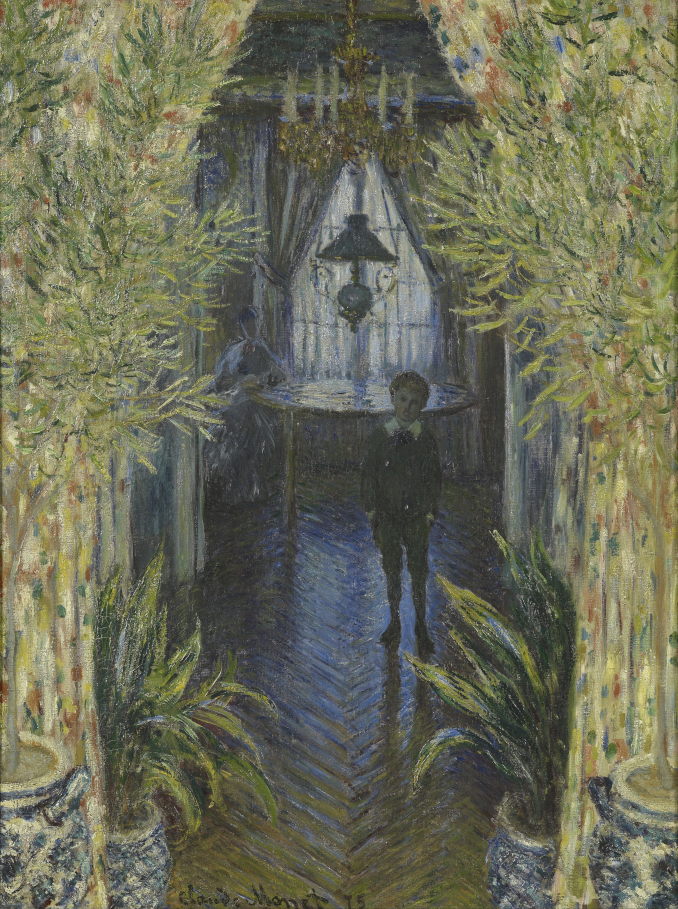

Another painting that was shown at the third exhibition was Monet’s A Corner of the Apartment—a picture featuring the artist’s son Jean and his wife Camille. The play of light and shadow inside an interior is decidedly Impressionist; stylistically, this picture is miles removed from anything a 19th-century academic painter could produce.

The Musée d’Orsay has also set up a companion event at the museum: a virtual reality (VR) experience of a visit to the original 1874 show, titled “Tonight with Impressionists.” VR technology has advanced since 2019, when the Louvre presented a “visit” to a Renaissance villa for that year’s da Vinci retrospective, but the experience still feels cumbersome. The idea is that you get to “walk” around 1874 Paris—visiting the original exhibition, watching Degas and Pissarro complain about their paintings not selling—and you can even take a peak at the Salon’s official show. The problem is that the headsets are still heavy and prone to giving you nausea. The idea is great; the execution is still waiting for the technology to catch up.

The best experience is still the same as it was in 1874—wandering around looking at the original Impressionist paintings, starting with the iconic Monet sunrise, and discovering how this explosion of modern, individualistic art began.

The “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism” exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay runs from March 26 to July 14, 2024.